This is my ninth year of blogging the A to Z Challenge. Everyday I will share something about my family’s life during 1950. This was a year that the USA federal census was taken and the first one that I appear in. At the end of each post I will share a book from my childhood collection.

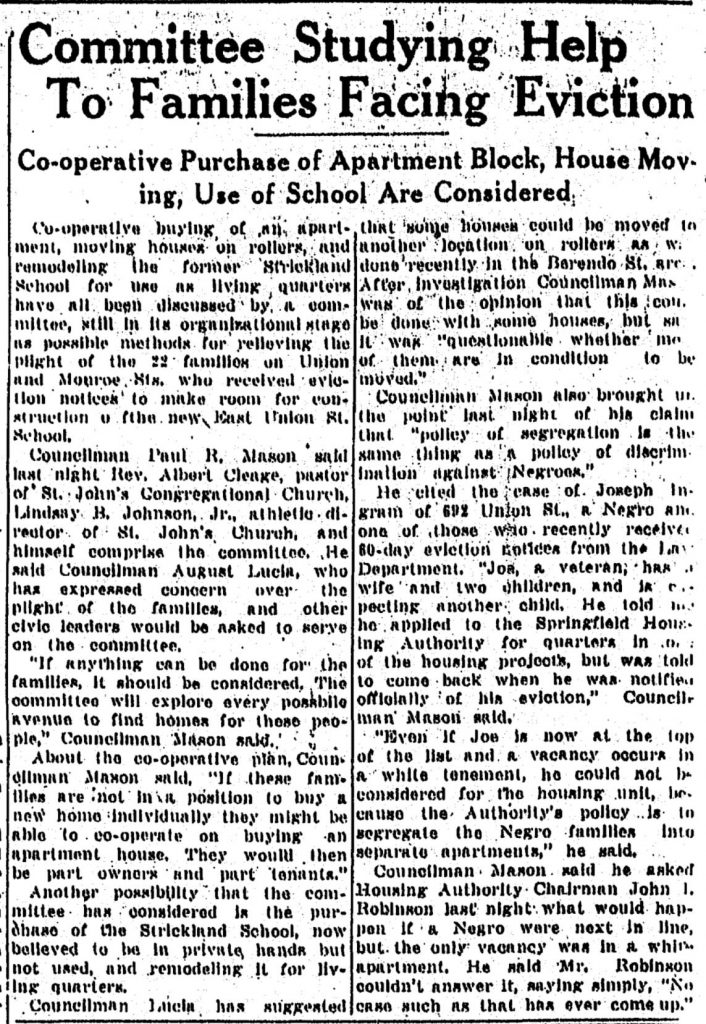

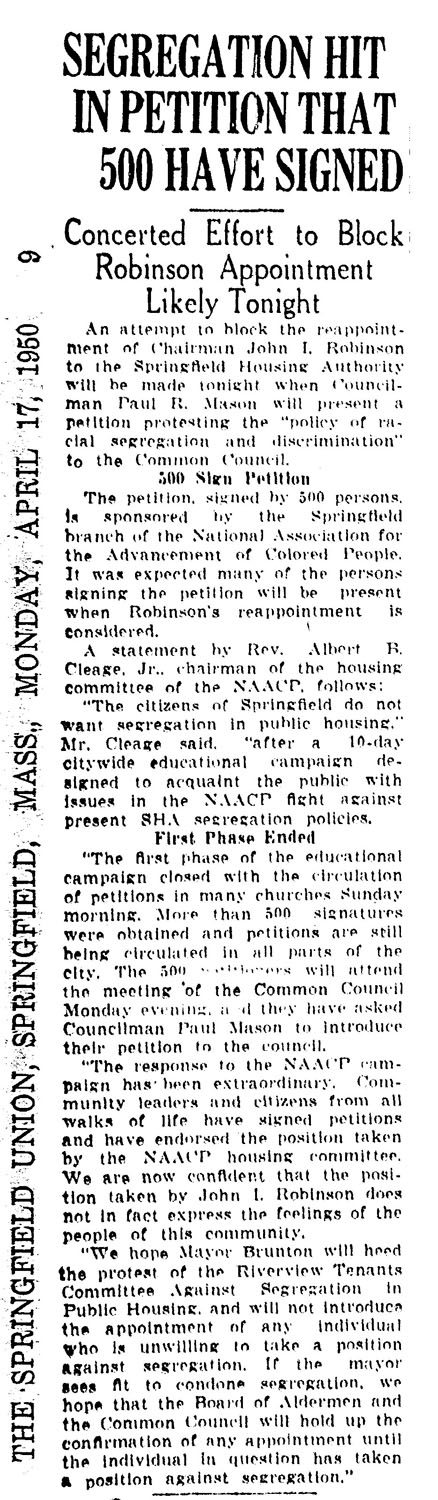

For the month of April, 1950 there were half a dozen articles about the committee that was trying to find ways to help families that were being evicted from the site of a new school. Over the month different plans were submitted, but there was always a hitch – the white potential neighbors didn’t want black people to move in; electrical wires would need to be moved; some of the houses were not in shape to be moved; and on and on. The plan was thus prevented from being put into action. In the end, the families were evicted and no new homes were provided. Here is the first article from the Springfield Union, February 23, 1950. Page 2

Committee Studying Help To Families Facing Eviction

Co-operative Purchase of Apartment Block, House Moving, Use of School Are Considered

Co-operative buying of an apartment, moving houses on rollers, and remodeling the former Strickland School for use as living quarters have all been discussed by a committee, still in its organizational stage as possible methods for relieving the plight of the 22 families on Union and Monroe Sts. who received eviction notices to make room for construction of the new East Union St. School.

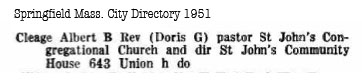

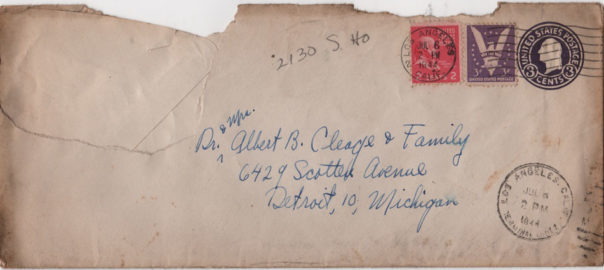

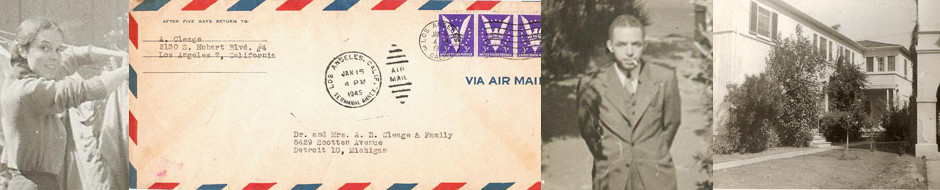

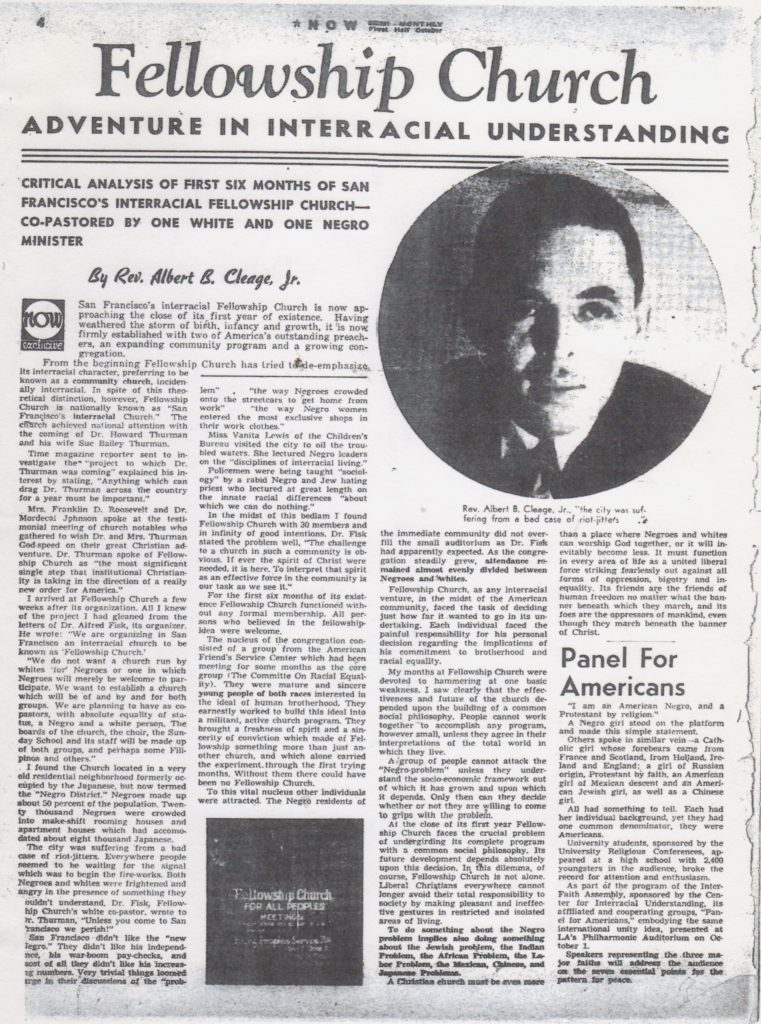

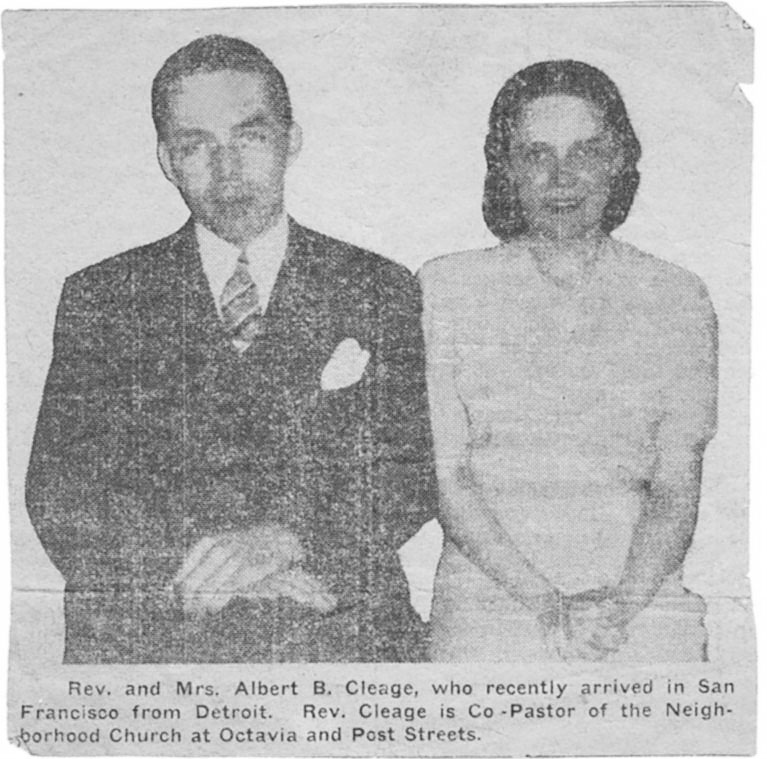

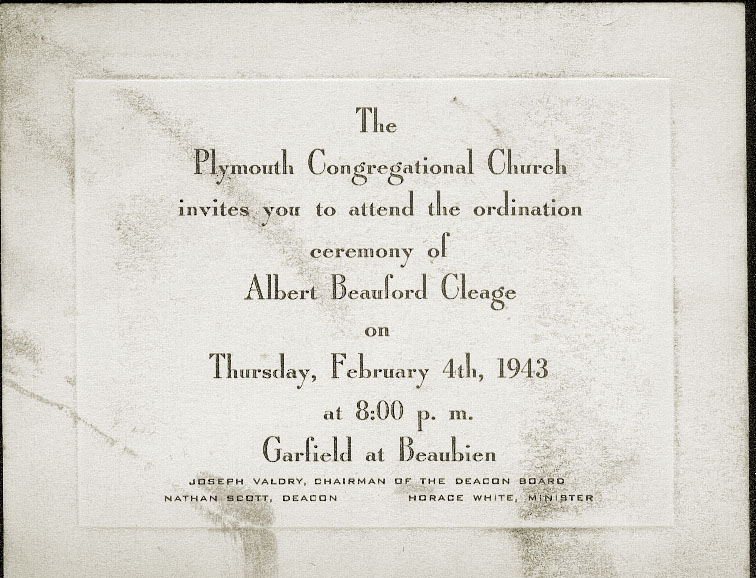

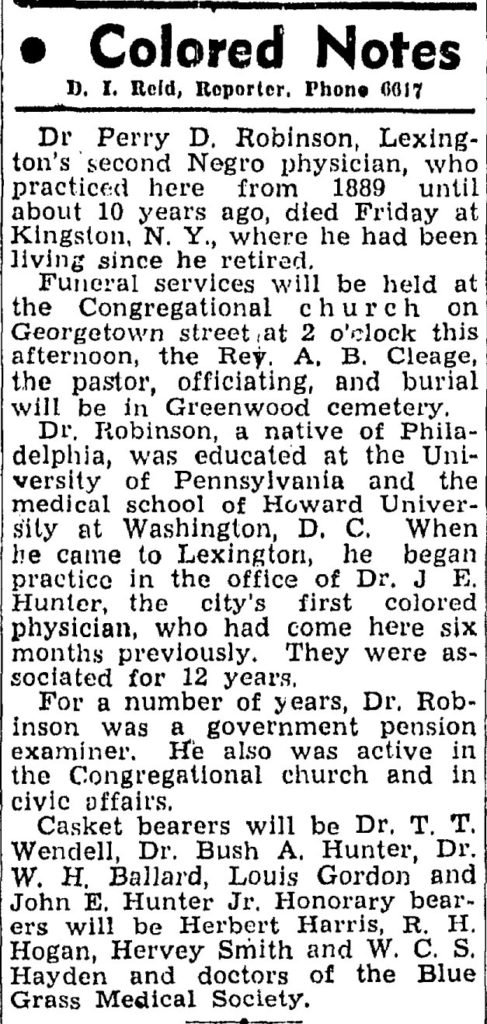

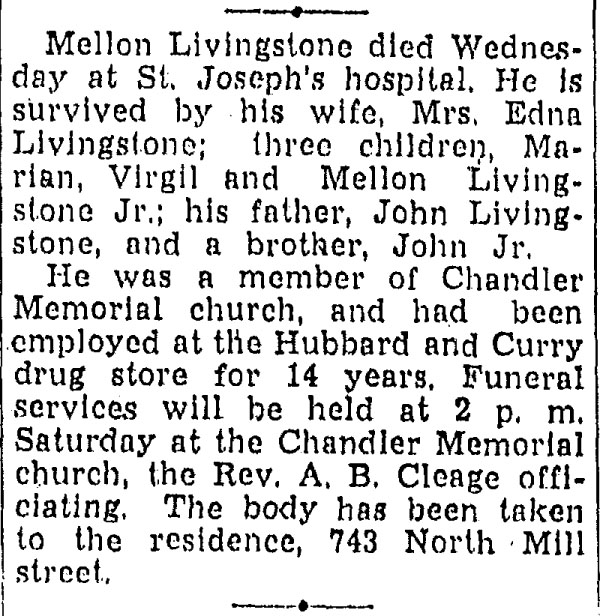

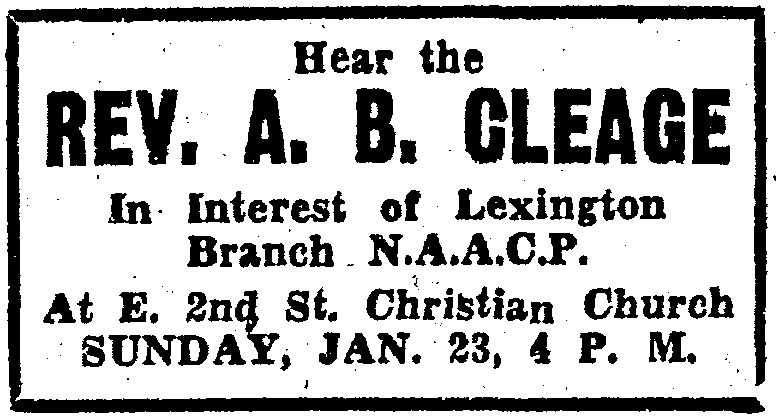

Councilman Paul R. Mason said last night Rev. Albert Cleage, pastor of St. John’s Congregational Church, Lindsay B. Johnson, Jr., athletic director of St. John’s Church, and himself comprise the committee. He said Councilman August Luca, who has expressed concern over the plight of the families, and other civic leaders would be asked to serve on the committee.

“If anything can be done for our families, it should be considered. The committee will explore every possible avenue to find homes for these people,” Councilman Mason said.”

About the co-operative plan, Councilman Mason said, “If these families are not in a position to buy a new home individually they might be able to co-operate on buying an apartment house. They would then be part owners and part tenants.”

Another possibility that the committee has considered is the purchase of the Strickland School, now believed to be in private hands, but not used and remodeling it for living quarters.

Councilman Lucia has suggested that some houses could be moved to another location on rollers as was done recently in the Barendo St. area. After investigation Councilman Mason was of the opinion that this could be done with some houses but said it was “questionable whether all of them are in condition to be moved.”

Councilman Mason also brought up the point last night of his claim that “policy of segregation is the same thing as a policy of discrimination against Negroes.”

He cited the case of Joseph Ingram of 693 Union St., a Negro and one of those who recently received a 60 day eviction notices from the Law Department. “Joe, a veteran, has a wife and two children, and is expecting another child. He told me applied to the Springfield Housing Authority for quarters in one of the housing projects, but was told to come back when he was notified officially of his eviction,” Councilman Mason said.

“Even if Joe is now at the top of the list and a vacancy occurs in a white tenement, he could not be considered for the housing unit, because the Authority’s policy is to segregate the Negro families into separate apartments,” he said.

Councilman Mason said he asked Housing Authority Chairman John I. Robinson last night what would happen if a Negro were next in line, but the only vacancy was in a white apartment. He said Mr. Robinson couldn’t answer it, saying simply, “No case such as that has ever come up.”