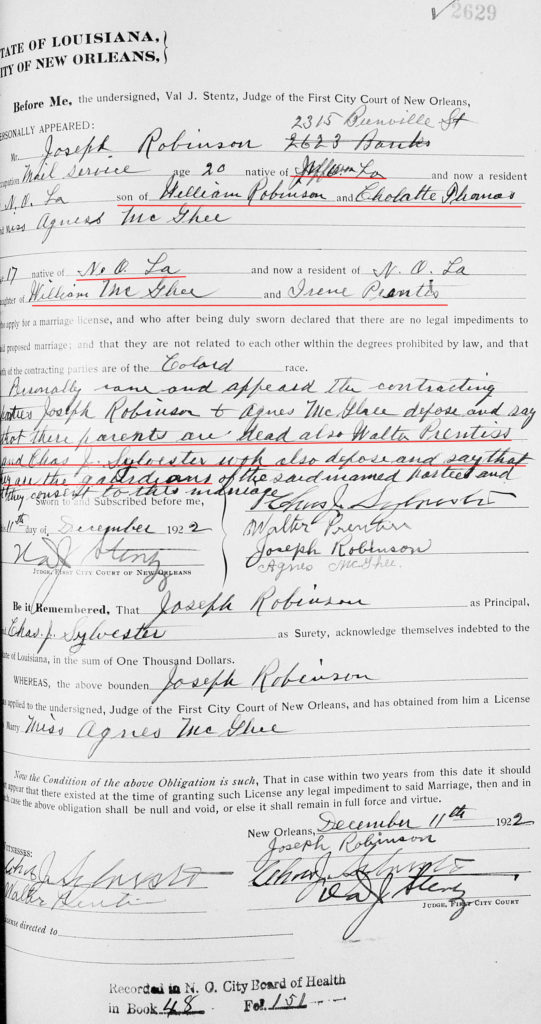

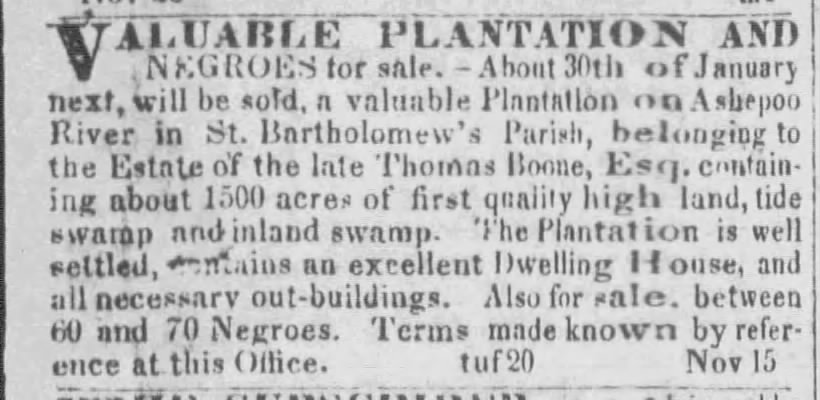

Agnes Primus was born into slavery in Maryland about 1835. When I found her, she was enslaved by Foster and Marietta Ray in Lebanon, Kentucky. Her two children were born there and were baptized at St. Augustine Catholic Church in Lebanon.

Agnes son John was born May 9, 1852. He was baptized by Rev. John B. Hutchins on March 4, 1853. Agnes was listed as the mother, a servant of Foster Ray. Although they use the word “servant” they were all enslaved.

Her daughter, Kate Elizabeth was born April 12, 1855 and baptized February 28, 1857 again by Rev. John B. Hutchins at St. Augustine Catholic Church. Agnes listed as mother, servant of Foster Ray.

Lebanon, Kentucky • Thu, Mar 29, 1962Page 1

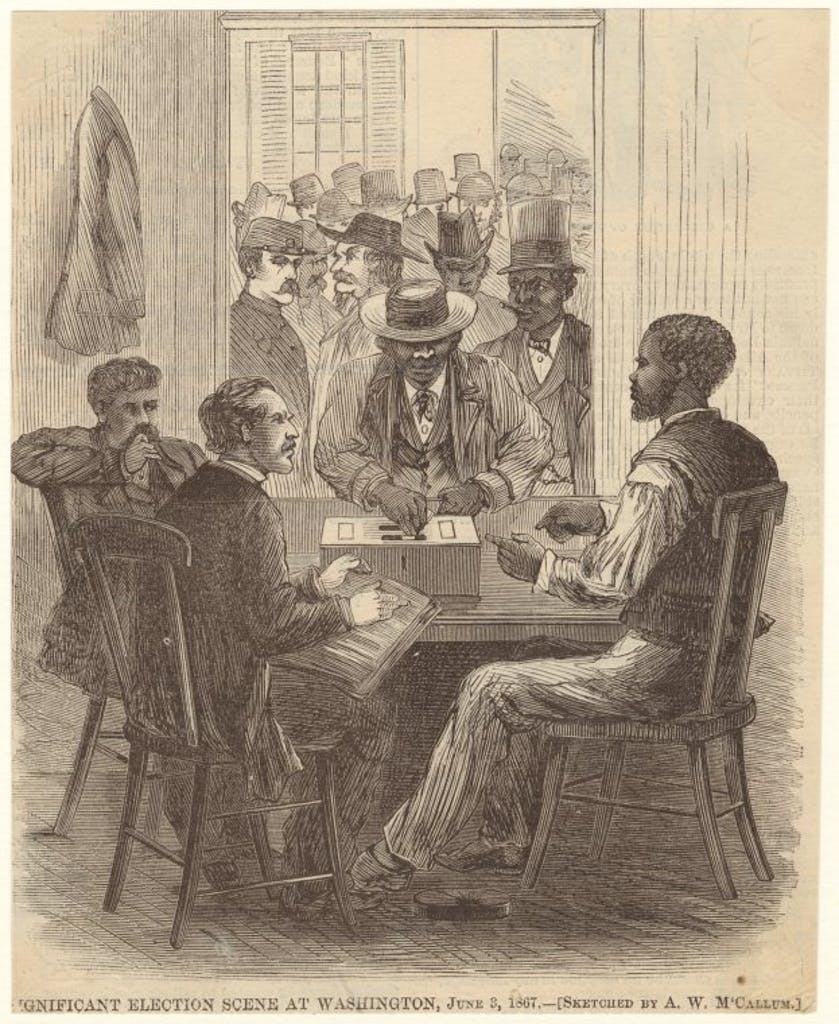

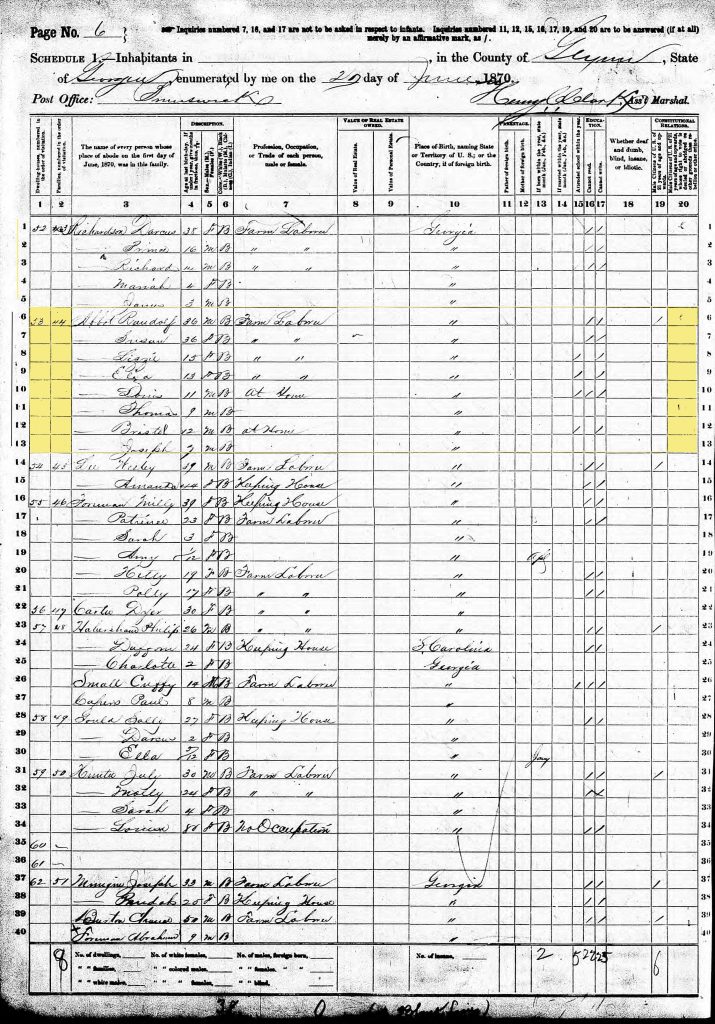

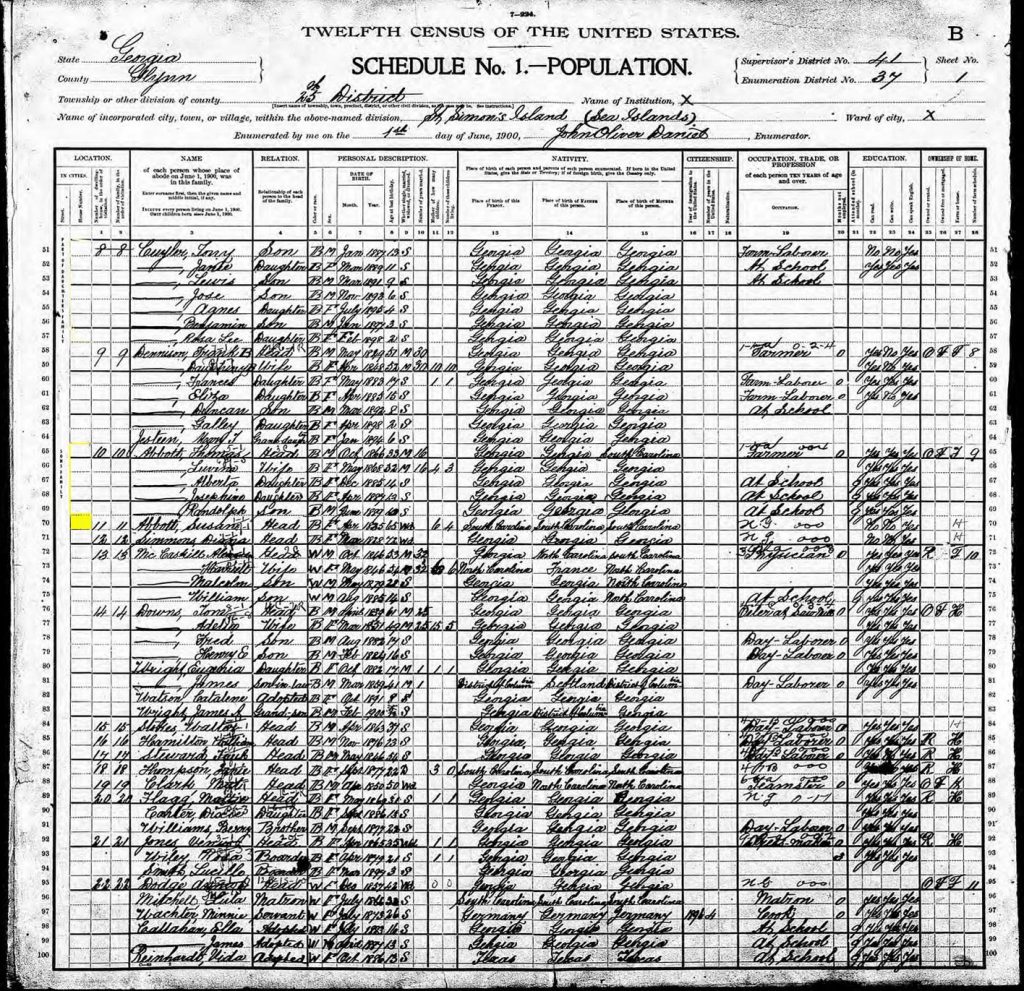

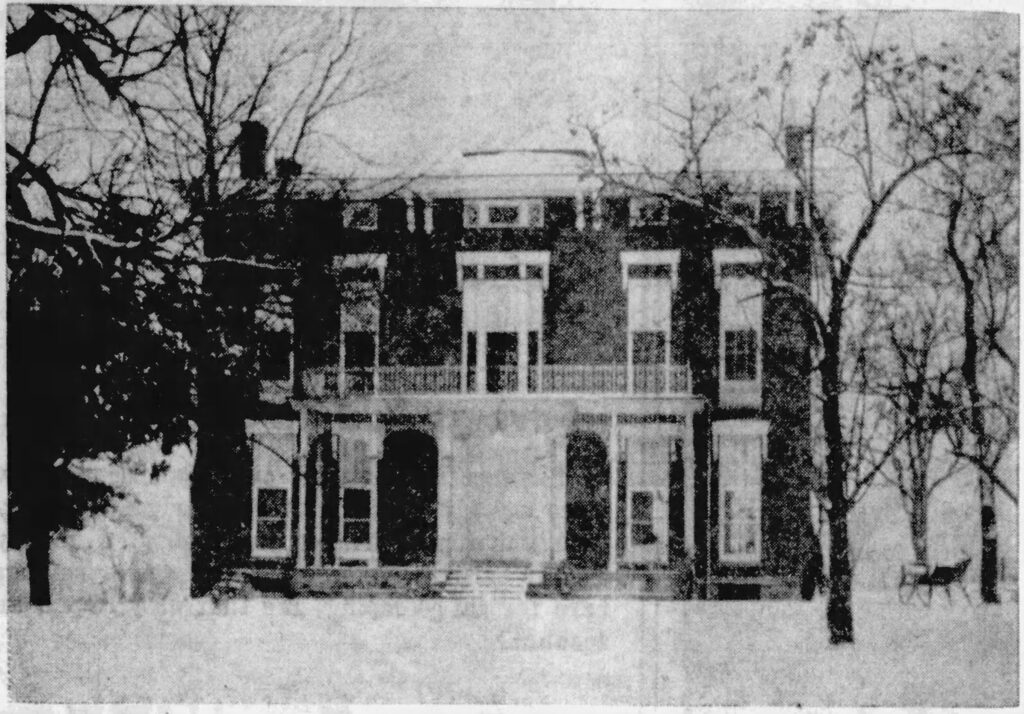

In the 1870 census, Agnes Primus and her two children, now 18 and 17, were among the servants enumerated in the household of Marietta and Colonel Thomas Foster. Col. Thomas Foster was listed as a farmer with real estate worth $324,150 and personal worth valued at $81,460. The photo above shows their large home. Living there were Marietta’s infirm mother Elizabeth Phillips, her 34 year old nephew/adopted son Hugh B. Ray, a little two year old Belle Phillips, and ten servants. The gardener and the nurse were identified as white. Both were literate. Six were identified as black and Agnes’ children as mulatto. Of the six, five were illiterate. Agnes could read and not write. Katie and John were literate.

_____________

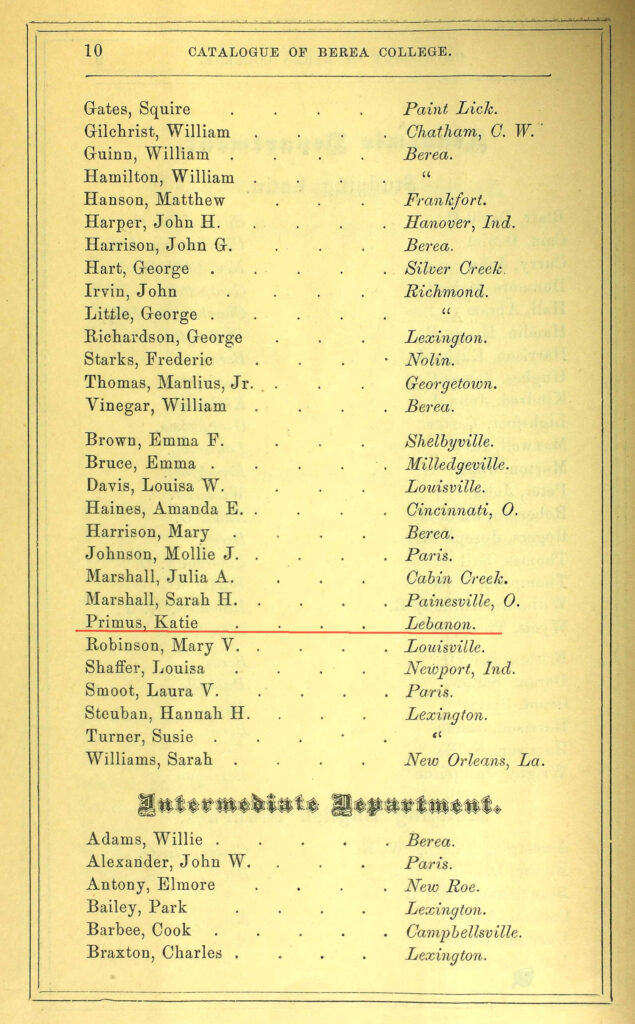

I was surprised to find Katie Primus as a student at Berea College during the 1870-1871 school year. The 1870 Census was taken during the summer so she could have been in Lebanon during the summer at Berea during the school year.

Berea College was founded in Madison County, Kentucky in 1855 by Kentucky abolitionists and educators. The school was integrated and the ministers associated with Berea preached and talked against slavery. After John Brown’s raid in 1859, sentiment ran high against the school. There were numerous mob actions until the staff left Kentucky en masses for points north with plans to return as soon as they could. After the Civil War, they were able to and established the school. Berea was not a college as we think of them today – subjects went from the very basics through the college curriculum. If you are interested, you can read more here.

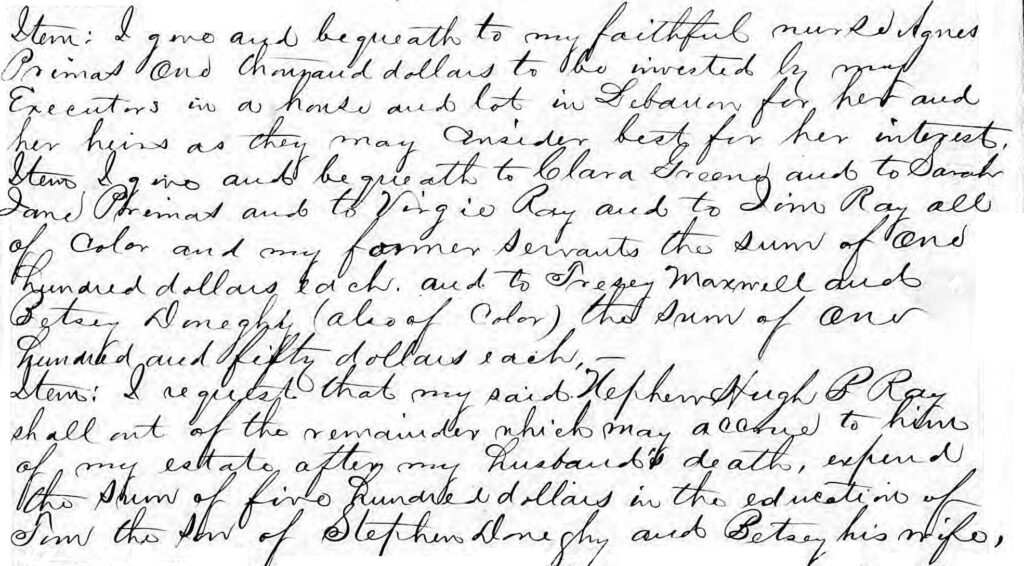

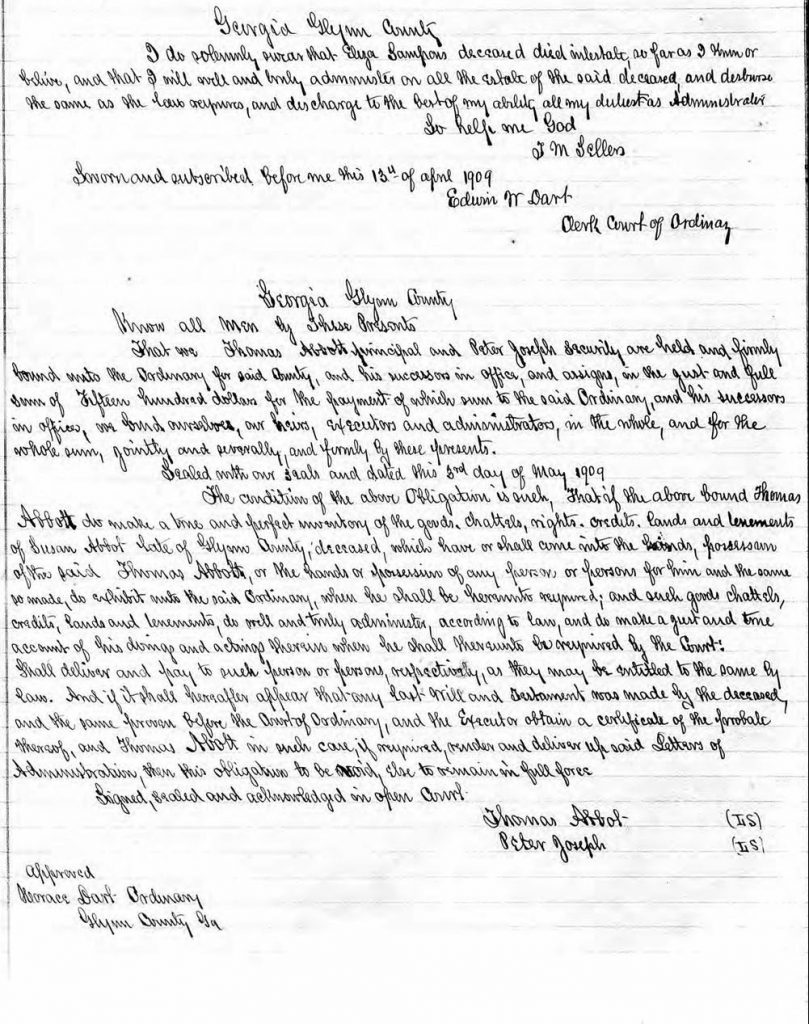

Will of Marietta Foster

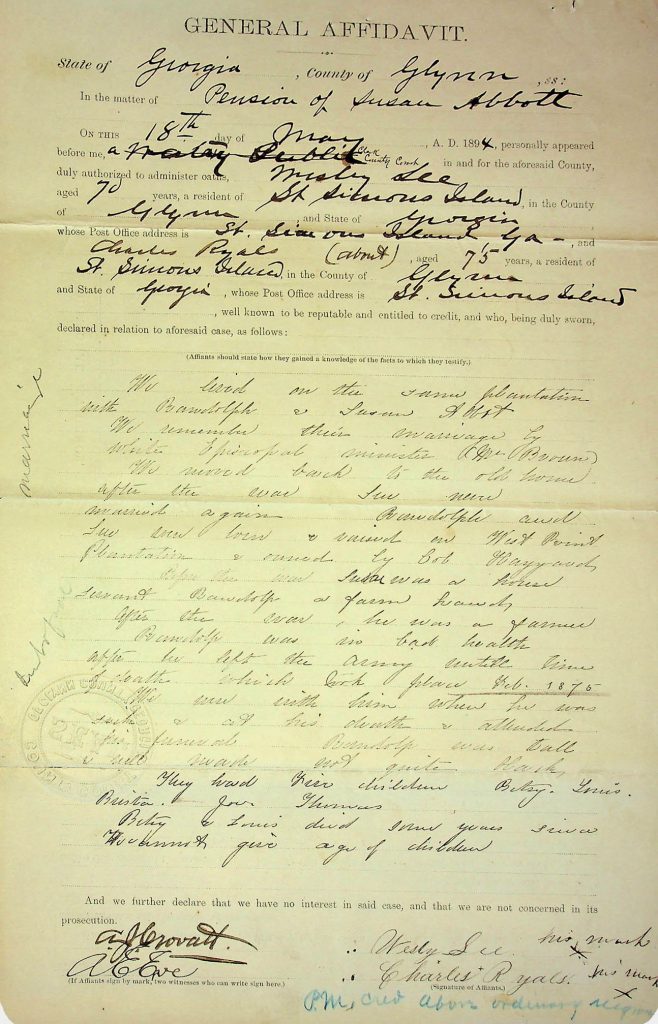

“Item: I give and bequeath to my faithful nurse Agnes Primas one thousand dollars to be invested by my executors in a house and lot in Lebanon for her and her heirs as they may consider best for her interests.”

Marietta Foster wrote her will November 20, 1871. Among other bequests, she left $1,000 to buy Agnes Primus a house. Marietta Foster died on January 9, 1872.

_____________

In the 1880 Census Agnes Primus was living with a different white family, Harrison and Mary Borders and their daughter Mary, who suffered from rheumatism. Harrison drove an express wagon. There were three servants.

Katie Primus worked as a servant and boarded with the James Smith family. Katie’s brother John Scott married James’ daughter, Hattie Smith later that year. Unfortunately, John died in 1881, soon before their daughter was born on November 20, 1881. Hattie named her John Scott, after her father. That was pretty confusing as I thought she must be a boy with that name. Rev. Peter Joseph DeFraine baptized John Scott Primus, six days later at St. Augustine Catholic Church. Katie Primus was the sponsor.

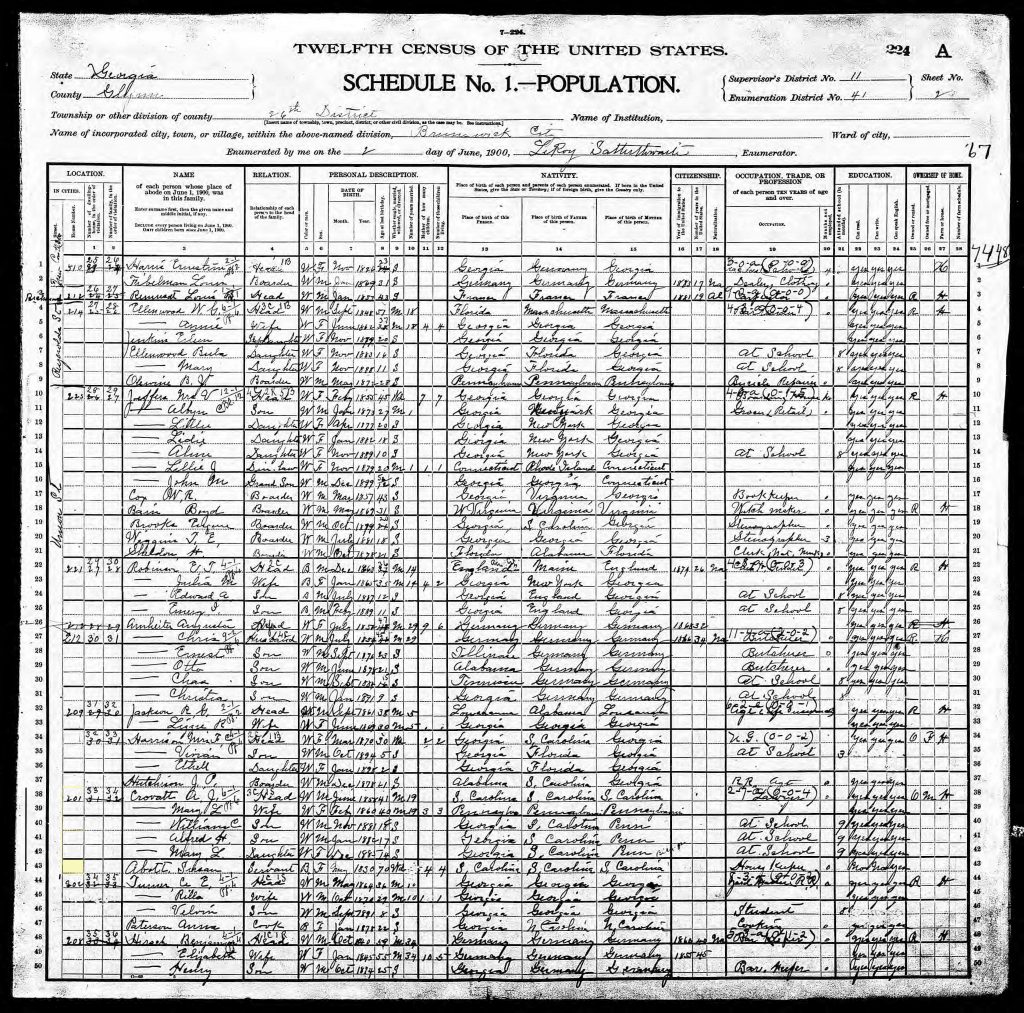

In 1885 Katie Primus married Henry C. Allen in Chicago, Ill. By 1900, they had three sons Primus, Guy and Stanley.

Agnes lived with Katie and her husband in Chicago until her death in 1919. She is buried in MT Olivet Catholic Cemetery.

At first Katie’s husband Henry worked as a waiter in a hotel. Later did catering. By 1920 they owned their home valued at $5,000 free of mortgage. In the early years, Katie did hairdressing. Later she had no occupation outside of the home. Through the years the house was full of family – sons, and grandchildren. Henry died in 1930. Katie followed him eight years later in 1938. She was buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery.

Agnes’ Grandchildren

John Scott Primus, born in 1882, chose to be known as Scottie Primus. She took her step father’s last name – Davis. Scottie became a high school English teacher. She taught in Kansas City, Missouri for many years, retiring to Louisville, Kentucky where she died in 1963.

The oldest was named Primus A. Allen was born in 1887. He completed the 6th grade. He was tall, slim with blue eyes. He married and had one son. Although he started his work life as a plasterer, he later became a red cap with railroads and continued with that. He lived with his brother Guy when he died in 1954.

Guy Eugene Allen was born in 1890. He completed four years of high school. He was tall, slender with brown eyes and brown hair. He and his wife had two sons. For awhile he worked as a postman. Later, Guy had his own business building and repairing houses. He owned his own home, right down the street from his brother Stanley. He died in 1986.

Stanley Henry Allen was born in 1892. He completed the 8th grade. He was medium height, medium weight with dark brown eyes, black hair and light brown complexion. He was a porter at the railroad station. He married but had no children. He owned his home when died in 1970.

____________

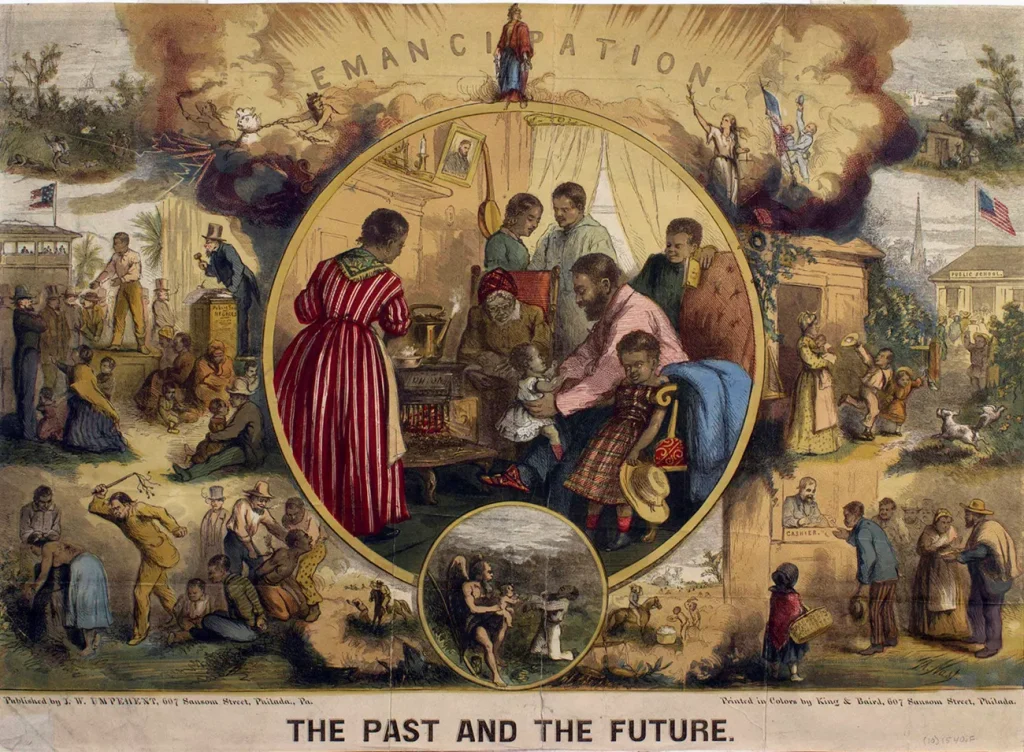

Agnes Primus and her family came a long way from slavery. I could not find any evidence that Agnes owned a home in Lebanon, Kentucky. Perhaps she did and sold it, financing her move with Katie to Chicago.

_____________