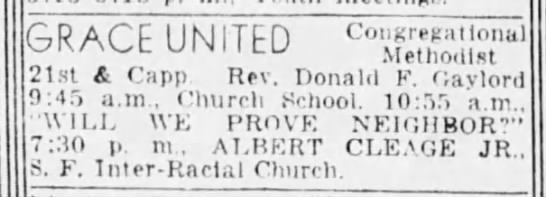

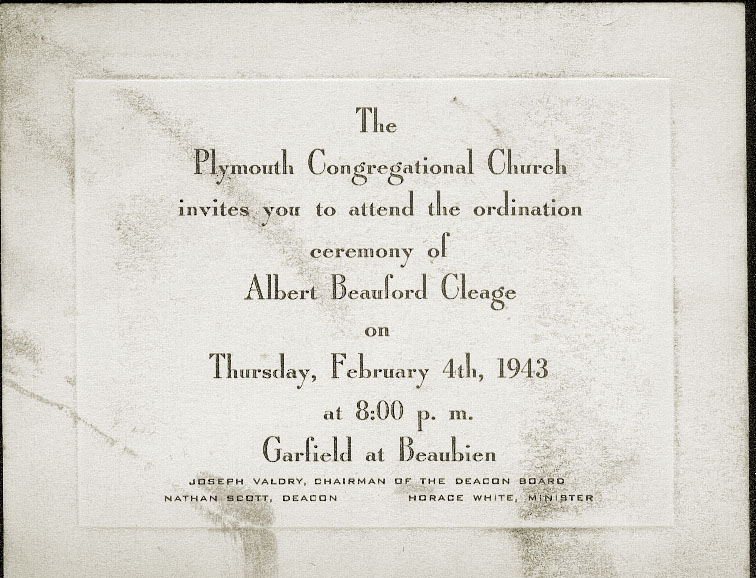

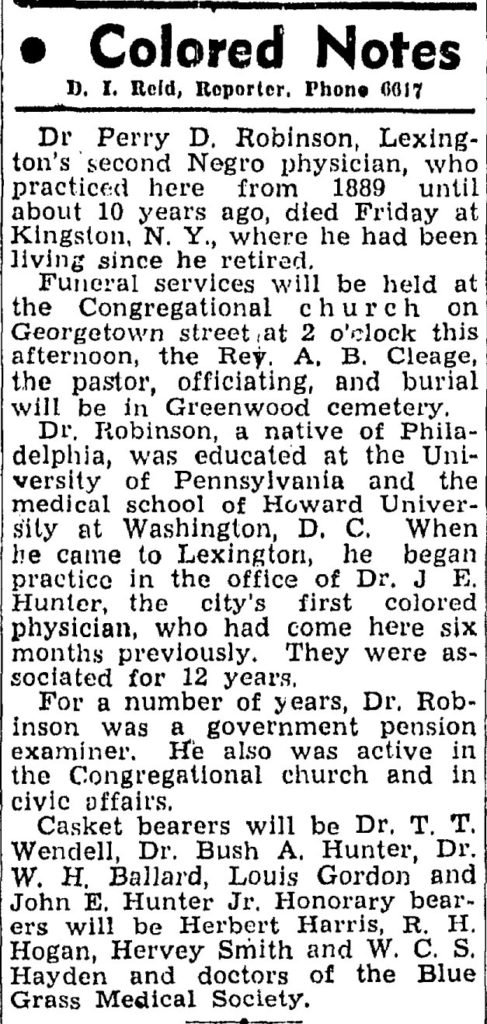

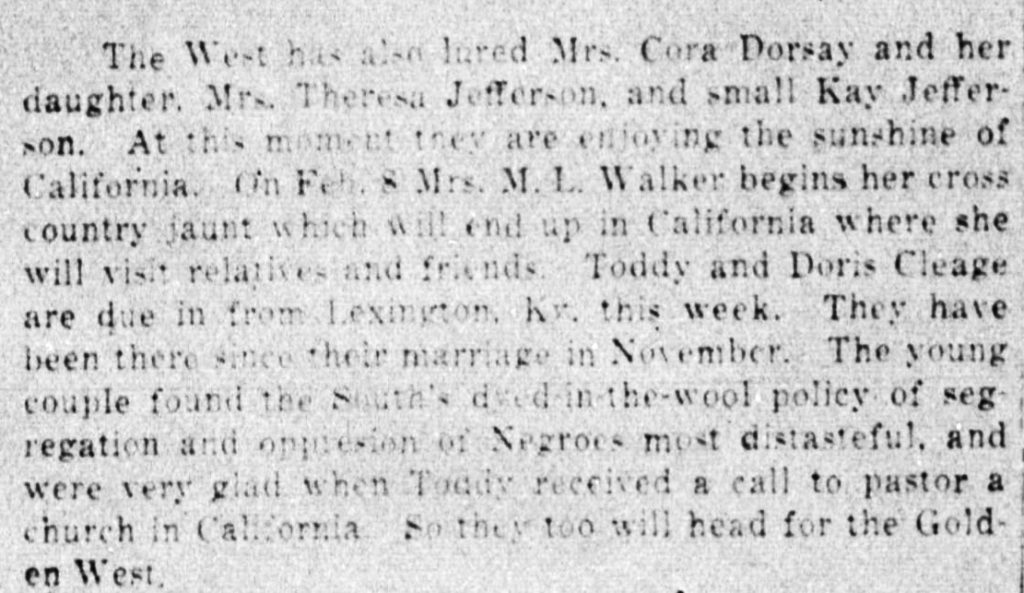

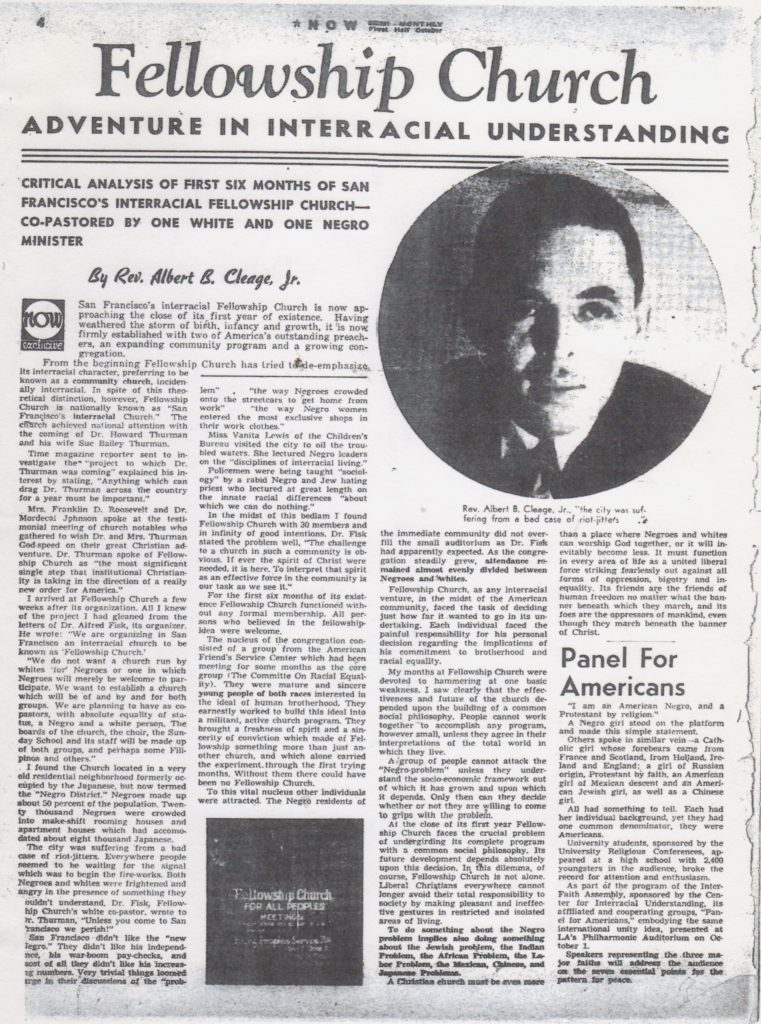

After leaving Chandler Memorial Church in Lexington in January of 1944, my parents traveled across county, by train to San Francisco, CA where my father, Rev. Albert B. Cleage, Jr. became co-pastor of the interracial Fellowship Church. Here is an article he wrote in October, 1946, about the experience after he had moved on to St. John’s Congregational Church in Springfield, MA. At the end of the transcription, there are links to other posts about the time in San Francisco.

San Francisco’s interracial Fellowship Church is now approaching the close of its first year of existence. Having weathered the storm of birth, infancy and growth, it is now, firmly established with two of America’s outstanding preachers, an expanding community program and a growing congregation.

From the beginning Fellowship Church has tried to de-emphasize its interracial character, preferring to be known as a community church, incidentally interracial. In spite of this theoretical distinction, however, Fellowship Church is nationally known as “San Francisco’s Interracial Church.” The church achieved national attention with the coming of Dr. Howard Thurman and his wife Sue Bailey Thurman.

Time magazine reporter sent to investigate the “project to which Dr. Thurman was coming” explained his interest by stating, “Anything which can drag Dr. Thurman across country for a year must be important.”

Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt and Dr. Mordecai Johnson spoke at the testimonial meeting of church notables who gathered to wish Dr. and Mrs. Thurman God-speed on their great Christian adventure. Dr. Thurman spoke of Fellowship Church as “the most significant single step that institutional Christianity is taking in the direction of a really new order for America.”

I arrived at Fellowship Church a few weeks after its organization. All I knew of the project I had gleaned from the letters of Dr. Alfred Fisk, its organizer. He wrote: “We are organizing in San Francisco an interracial church to be known as ‘Fellowship Church.’

We do not want a church run by whites ‘for’ Negroes or one in which Negroes will merely be welcome to participate. We want to establish a church which will be of and by and for both groups. We are planning to have as co-pastors, with absolute equality of status, a Negro and a white person. The boards of the church, the choir, the Sunday School and its staff will be made up of both groups, and perhaps some Filipinos and others.”

I found the Church located in a very old residential neighborhood formerly occupied by the Japanese, but now termed the “Negro District.” Negroes made up about 50 percent of the population. Twenty thousand Negroes were crowded into make-shift rooming houses and apartment houses which had accommodated about eight thousand Japanese.

The city was suffering from a bad case of riot-jitters. Everywhere people seemed to be waiting for the signal which was to begin the fire-works. Both Negroes and whites were frightened and angry in the presence of something they couldn’t understand. D. Fisk, Fellowship Church’s white co-pastor, wrote to Dr. Thurman, “Unless you come to San Francisco we perish!”

San Francisco didn’t like the “new Negro.” They didn’t like his independence, his war-boom pay-checks, and most of all they didn’t like his increasing numbers. Very trivial things loomed large in their discussions of the “problem”, “the way Negroes crowded onto the streetcars to get home from work” “the way Negro women entered the most exclusive shops in their work clothes.”

Miss Vanita Lewis of the Children’s Bureau visited the city to oil the troubled waters. She lectured Negro leaders on the “disciplines of interracial living.”

Policeman were being taught “sociology” by a rabid Negro and Jew hating priest who lectured at great length on the innate racial differences “about which we can do nothing.”

In the midst of this bedlam I found Fellowship Church with 30 members and an infinity of good intentions. Dr. Fisk stated the problem well, “The challenge to a church in such a community is obvious. If ever the spirit of Christ were needed it is here. To interpret that spirit as an effective force in the community is our task as we see it.”

For the first six months of its existence Fellowship Church functioned without any formal membership. All persons who believed in the fellowship-idea were welcome.

The nucleus of the congregation consisted of a group from the American Friend’s Service Center which had been meeting for some months as the core group (The Committee On Racial Equality). They were mature and sincere young people of both races interested in the ideal of human brotherhood. They earnestly worked to build this ideal into a militant active church program. They brought a freshness of spirit and a sincerity of conviction which made of Fellowship something more than just another church, and which alone carried the experiment through the first trying months. Without them there could have been no Fellowship Church.

To this vital nucleus other individuals were attracted. The Negro residents of the immediate community did not overfill the small auditorium as Dr. Fisk had apparently expected. As the congregation steadily grew, attendance remained almost evenly divided between Negroes and whites.

Fellowship Church, as any interracial venture, in the midst of the American community, faced the task of deciding just how far it wanted to go in its undertaking. Each individual faxed the painful responsibility for his personal decision regarding the implications of his commitment to brotherhood and racial equality.

My months at Fellowship Church were devoted to hammering at one basic weakness. I saw clearly that the effectiveness and future of the church depended upon the building of a common social philosophy. People cannot work together to accomplish any program, however small, unless they agree in their interpretations of the total world in which they live.

A group of people cannot attack the “Negro-problem” unless they understand the socioeconomic framework out of which it has grown and upon which it depends. Only then can they decide whether or not they are willing to come to grips with the problem.

At the close of its first year Fellowship Church faces the crucial problem of undergirding its complete program with a common social philosophy. Its future development depends absolutely upon this decision. In this dilemma, of course, Fellowship Church is not alone. Liberal Christians everywhere cannot longer avoid their total responsibility to society by making pleasant and ineffective gestures in restricted and isolated areas of living.

To do something about the Negro problem implies also doing something about the Jewish problem, the Indian Problem, the African Problem, the Labor Problem, the Mexican, Chinese and Japanese Problems.

A Christian church must be even more thank a place where Negroes and whites can worship God together, or it will inevitably become less. It must function in every area of life as a united liberal force striking fearlessly out against all forms of oppression, bigotry and inequality. Its friends are the friends of human freedom no matter what the banner beneath which they march, and its foes are the oppressors of mankind, even though they march beneath the banner of Christ.

________________

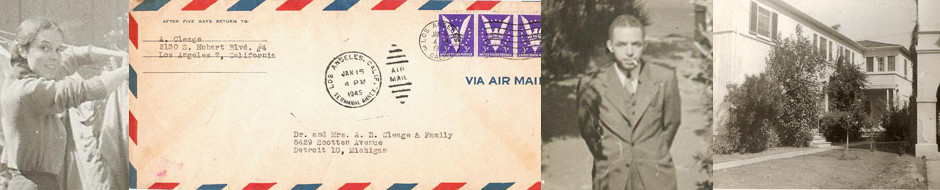

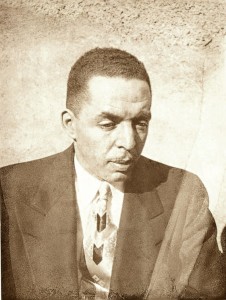

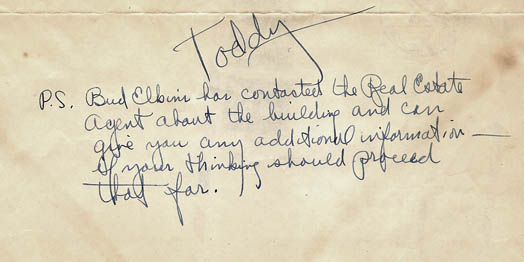

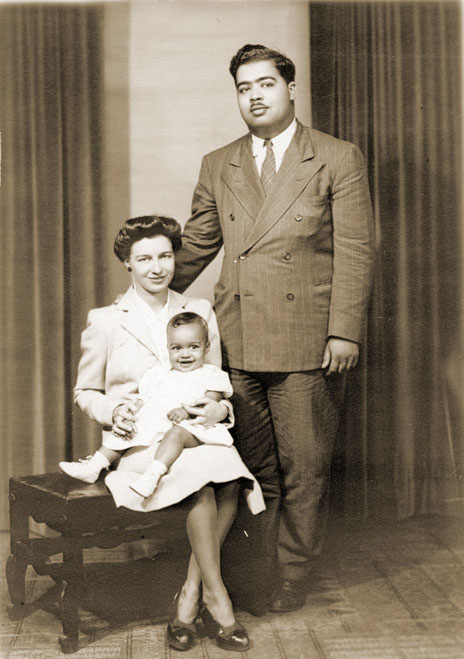

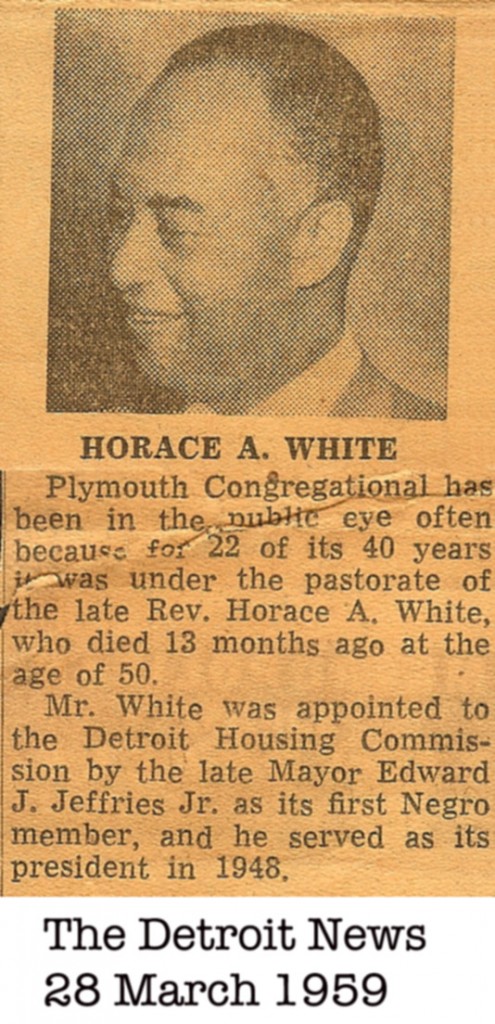

My Parents Time in San Francisco

Newspaper Clipping of My Parents in San Francisco 1944

Hanging Up Laundry