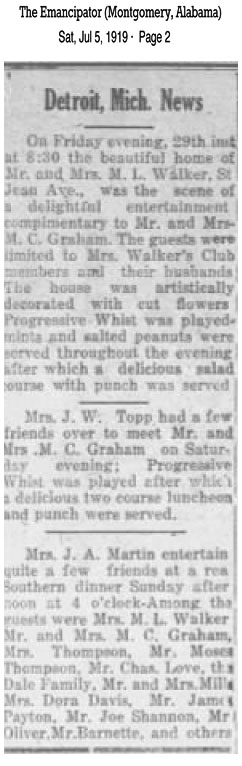

This year I am going through an alphabet of news items taken from The Emancipator newspaper, published between 1917 and 1920 in Montgomery, Alabama. Most are about my grandparent’s circle of friends. Each item is transcribed directly below the clipping. Click on any image to enlarge.

____________

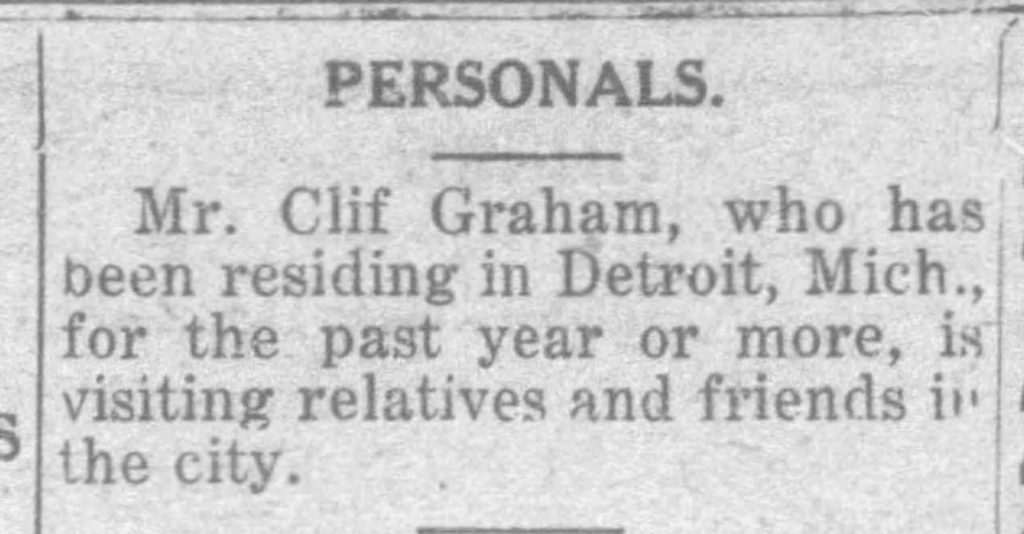

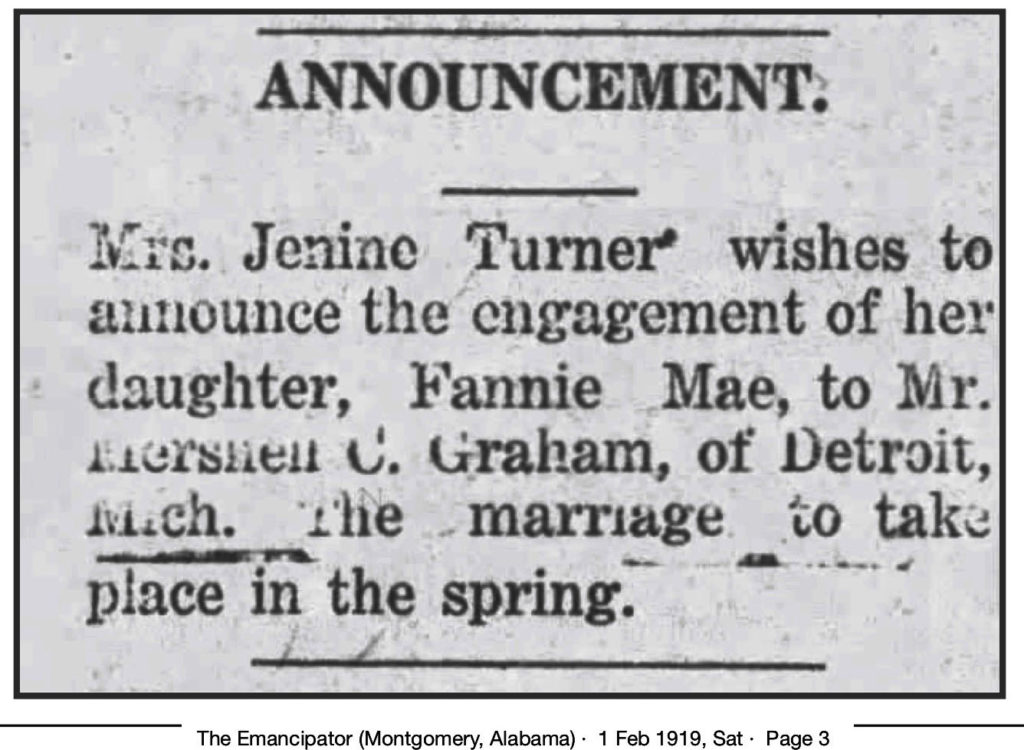

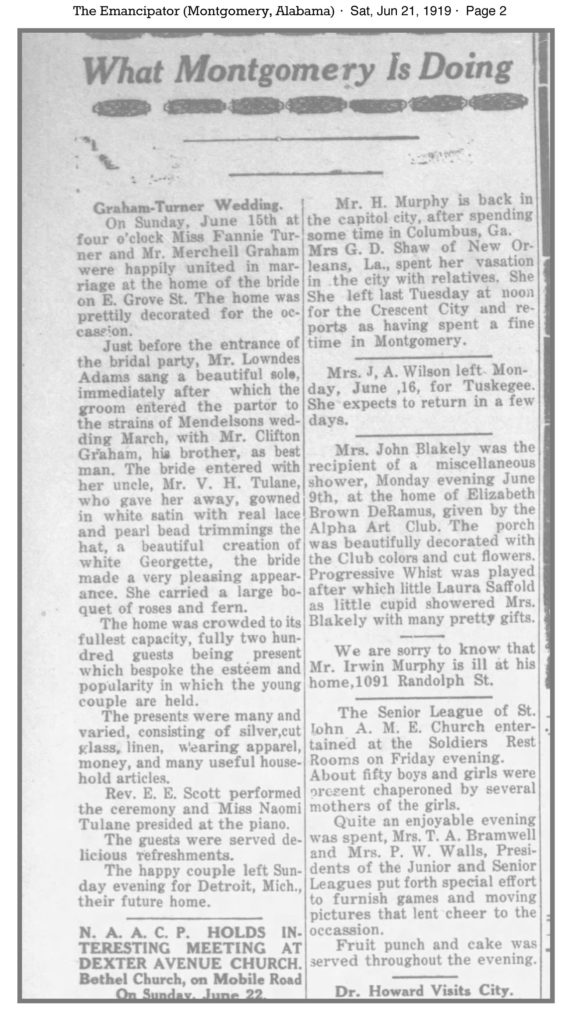

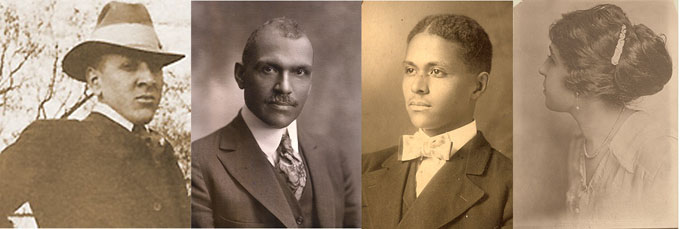

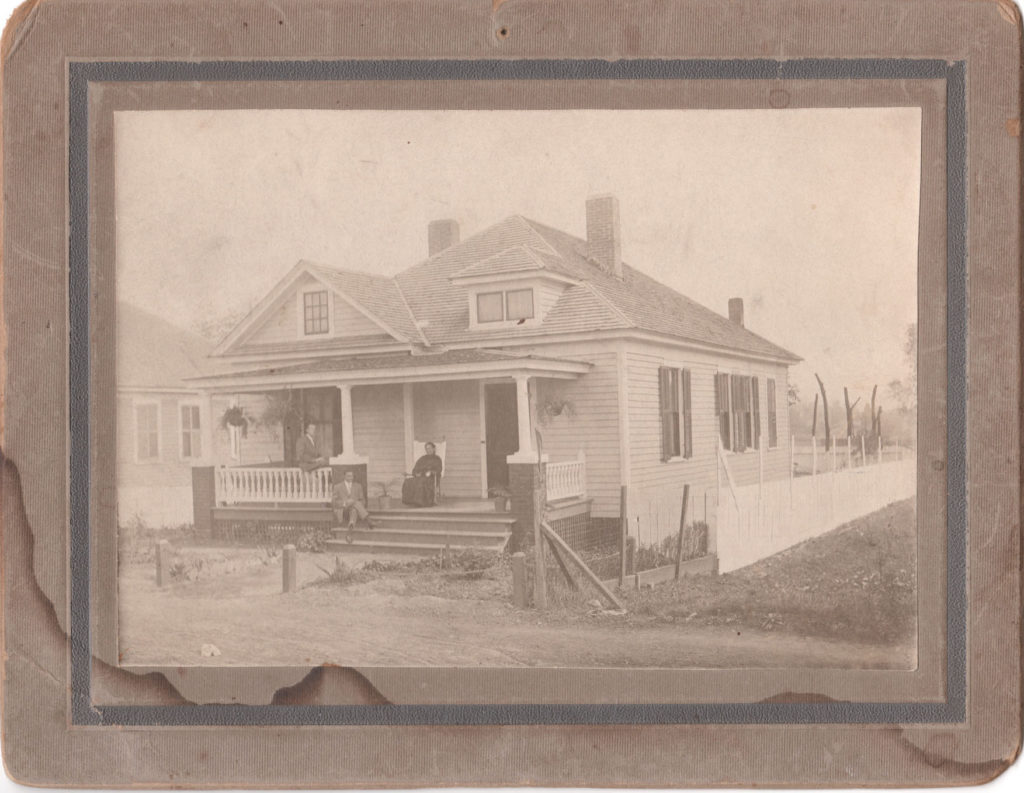

Clifton Graham was the best man at my grandparent’s wedding.

“Mr. Clif Graham, who has been residing in Detroit, Mich., for the the past year or more, is visiting relatives and friends in the city.”

Clifton Graham and his family were always referred to as my grandfather Mershell Graham’s adopted family. He wasn’t raised by them and we all knew his birth family was in Coosada, Alabama. I never asked why he had adopted them as his family. I always assumed it was because he was friends with Clifton and they shared the name of “Graham”. Now everybody I could have asked is gone.

Clifton Graham was born July 13, 1889 in Montgomery, Alabama. He was the fifth of the five children of Joseph and Mary (Rutledge) Graham – Callie, William, Joseph, Mattie and John Clifton. Four of the children survived to adulthood.

Callie married when she was 18 and remained in Perry County when the family relocated to Montgomery in the late 1880s. William disappeared after the 1880 census and never reappears. Joseph, Mattie and John moved with their parents to Montgomery.

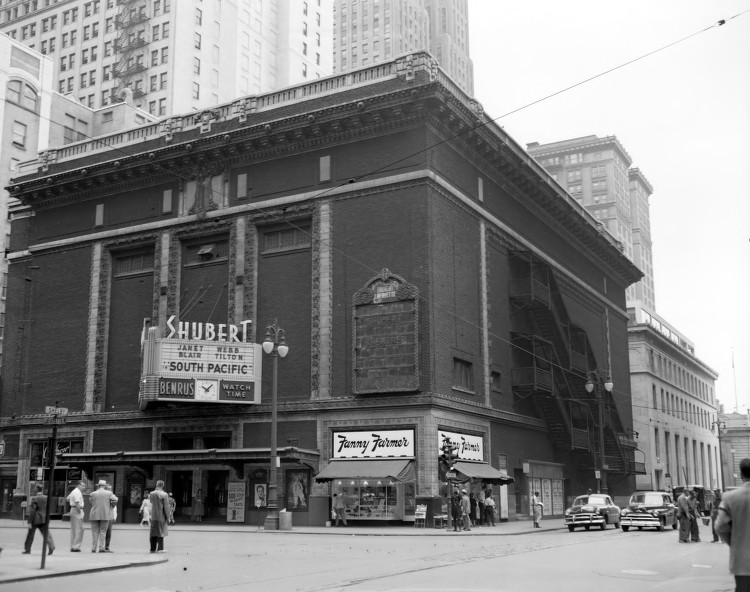

Both Clifton and his older sister Mattie attended college for several years. He was drafted in July of 1918, married Gwendolyn Lewis the following month and was released from the army in March 1919. While Clifton was in the army and before their son was born, Gwendolyn taught school. Their first son, John Clifton Jr. was born in Montgomery. They moved to Detroit and the second son, Lewis, was born there. In the 1930 Census Clifton Graham worked as a prohibition agent. Later he continued to work for the government.

Clifton’s sister and mother also moved to Detroit. Gwendolyn’s brother, Lafayette Billingsly Lewis moved with their mother to Chicago around the same time.

__________________

I found this information on Ancestry.com in Census Records, Directories, Death Records, Military Records and Marriage Records. News items were found on Newspapers.com. I also use Google Maps. The photograph is from my family photos.