Another unlabeled photograph from my Cleage collection. Photographer one of the Cleages. Taken in Detroit. Probably in the 1940s.

Another unlabeled photograph from my Cleage collection. Photographer one of the Cleages. Taken in Detroit. Probably in the 1940s.

My father, then Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr, me, my mother Doris Graham Cleage, my step-father and uncle Henry Cleage. Summer of 1966.

My father, then Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr, me, my mother Doris Graham Cleage, my step-father and uncle Henry Cleage. Summer of 1966.

Sitting on the couch, braiding my hair with my mother and sister Pearl. 1963. My son James walking across the room summer of 2017.

Sitting on the couch, braiding my hair with my mother and sister Pearl. 1963. My son James walking across the room summer of 2017.

I had just come in from the Association of Black Students’ Symposium at Wayne State in February of 1968.

I had just come in from the Association of Black Students’ Symposium at Wayne State in February of 1968.

Other posts about 5397 Oregon.

Detroit Then and Now – Other then and now photographs

“O” is for Oregon Street – Memories of living in the house on Oregon.

My cousins lived upstairs in a 4-family flat on the corner of McDougall and Hunt Street on the East Side of Detroit. Their mother, Mary V. Graham Elkins, was my mother’s sister. She worked as a secretary at the County Building.

Their father, Frank “Bud” Elkins, graduated with honors from Cass Technical high school in the late 1930s. As an electrician, he tried to join the Electricians Union but as a black man was barred. He set up his own shop as an independent Electrician. He drove a truck with “Elkins Electric Company” on the side. I remember riding in it a few times. There were not seats for all and we sat on the floor.

Some other stories about this family:

Remembering Barbara Lynn Elkins

In 1951 our family moved from Springfield, MA to Detroit, where my father, Rev. Albert B. Cleage, Jr., was called as pastor of St. Marks United Presbyterian Community Church at Twelfth and Atkinson. My paternal grandparents lived several blocks up Atkinson. The parsonage was right down the block from them. He was there until 1953 when there was a church split. My father and 300 members started a new church that became Central Congregational Church and finally The Shrine of the Black Madonna.

Here are links to two blog posts about these events, Moving Day – Springfield to Detroit 1951, A Church and Two Brothers .

Below are some then and now photographs of St. Mark’s and the parsonage at 2212 Atkinson.

After church at St. Mark’s Community United Presbyterian Church in 1953 combined with a 2011 photograph taken by Benjamin Smith. In the group near the door I see myself, my sister Pearl, my mother Doris Graham Cleage, my uncle Henry Cleage and Choir director Oscar Hand leaning out of the door.

In front of St. Marks 1953. I see my mother in the dark suit and part of my little sister Pearl behind her in a light colored dress. Combined with another photograph by Benjamin Smith. This photo and the one below first appeared in the blog post “A Sunday After Church About 1953“

The parsonage now and us back in 1953 before the church split. This photograph first appeared in the blog post “Then and Now – Atkinson About 1953″.

Recently my son James was in Detroit and visited many of the sites that were important in my life and my family’s life. He was lucky enough to have historian Paul Lee and Sala Adams as guides. I have matched photographs from the 1960s with some of the photos that they took last week.

Today’s photographs were taken at 5397 Oregon, on the West Side of Detroit. Ten years ago when I went around taking photos of places I had lived, there were people living here. Today the house and many in the area are wrecks. In one photo not shown here, I could see holes in the roof. The house on the left still has someone living there. The two houses to the right are also falling to pieces. It’s tragic.

I would never have imagined that this area would look like this when I lived there some 48 years ago. Today I’ve been looking at the house I live in right now and thinking about which parts would fall apart first if it were vacant for a decade. I doubt it would be in as good a shape as this one because it was built with much cheaper materials.

You can read about my life in this house here “O” is for Oregon Street. This is the first of a series.

My sister Pearl patting goat while being held by my mother. The back of my head is visible on the lower right. This is probably at the petting zoo on Belle Isle in Detroit, Michigan. Taken in 1952 when Pearl was 3.

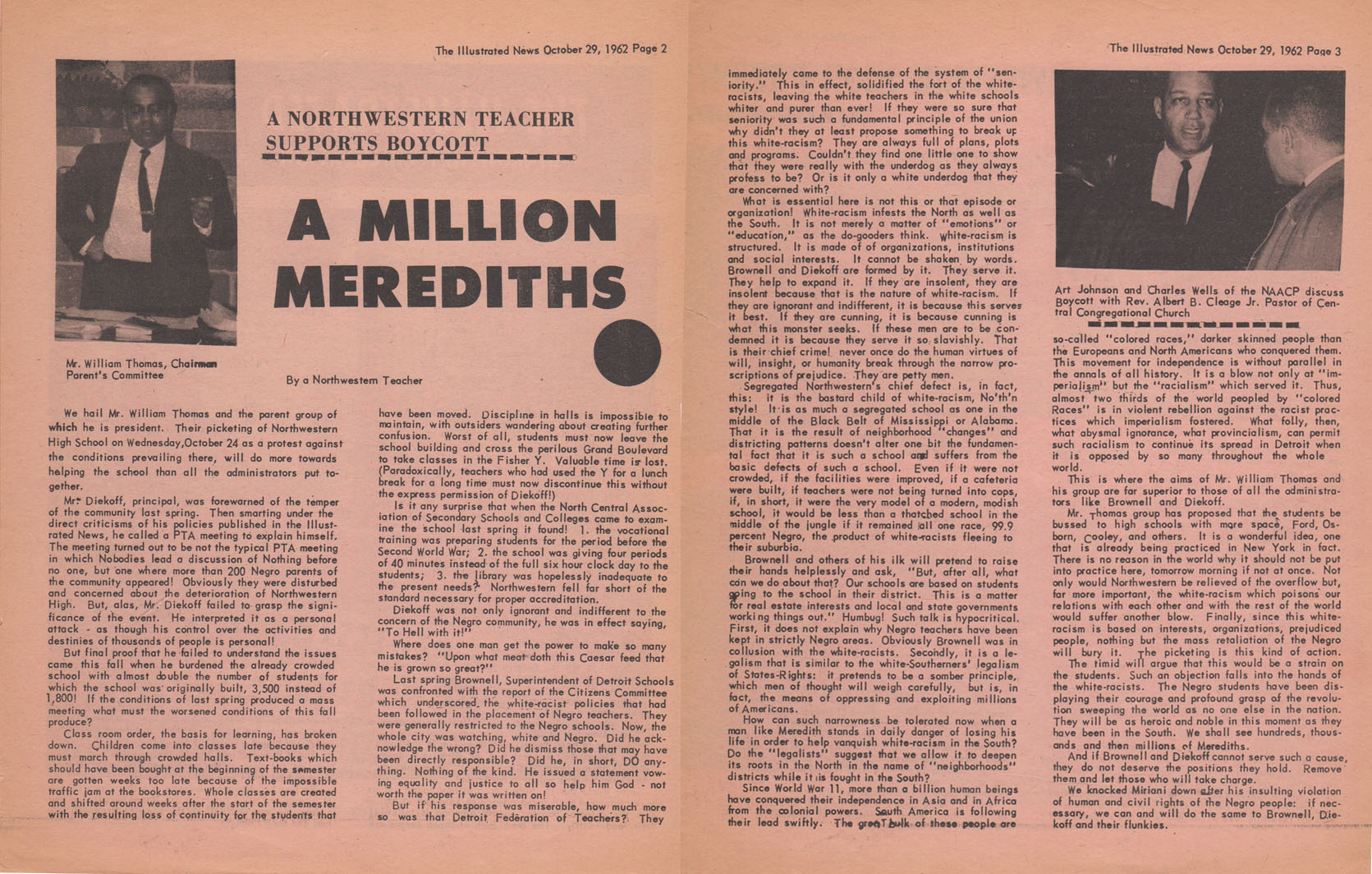

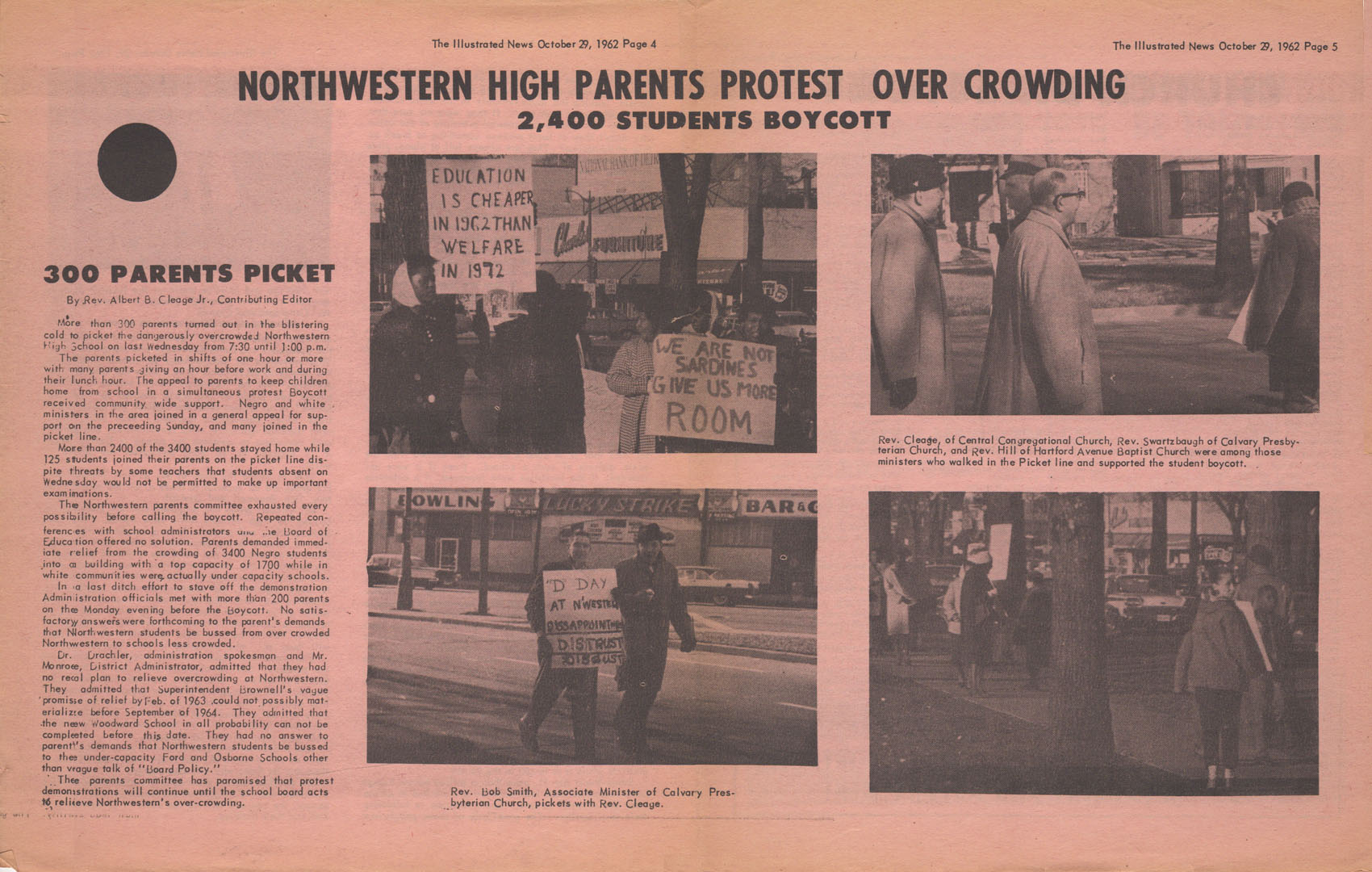

Reading about the present teacher’s sick out and the student walkouts in Detroit reminded me of this boycott of Northwestern High School in 1962. I was a junior and remember picketing in the cold. Several students from our church Youth Fellowship came and picketed with us even though they were students at Cass. Most of my classmates went to school that day, I particularly remember one of my friends said she was not going to stay home because she didn’t want to miss a day at school. Sometime later students from Northwestern were bused out to the white schools with vacant seats.

Click any of the images to enlarge for reading.

My sister Pearl in the checked pants carrying the sign. My father on the far right side walking towards Pearl.

I am pretty sure “A Northwestern Teacher” was Ernest Smith, an activist and member of my father’s church.

I am in the front bottom right photo, turning backwards with the high water pants.

While looking through old copies of The Illustrated News for something completely unrelated, I came across this advertisment for Vicki’s Bar-B-Que. I noticed the oven and immediately thought of the Sepia Saturday prompt for this week. I decided to google Vicki’s and see if there were any photographs or other ads from the past. Imagine my surprise when I found that the restaurant is still operating and that the same family still owns it!

Although I do not remember ever eating at Vicki’s or tasting their sauce, I was able to find a family member who has been to the restaurant recently and she said, “Yes. Vicki’s is still there. Some people love it! I’m not a fan but I’ve only been there once. Maybe it was a bad day. They have the kind of bbq that is grilled meat and then you dip it on the sauce instead of grilling and caramelizing the sauce while grilling.”

You can see an interview with the present owner, the oldest son of the original family, and photos of the food and building, plus reviews of the present food and service at this link Vicki’s Yelp Page. The link to the video is just under the photos of the restaurant at the top of the page.

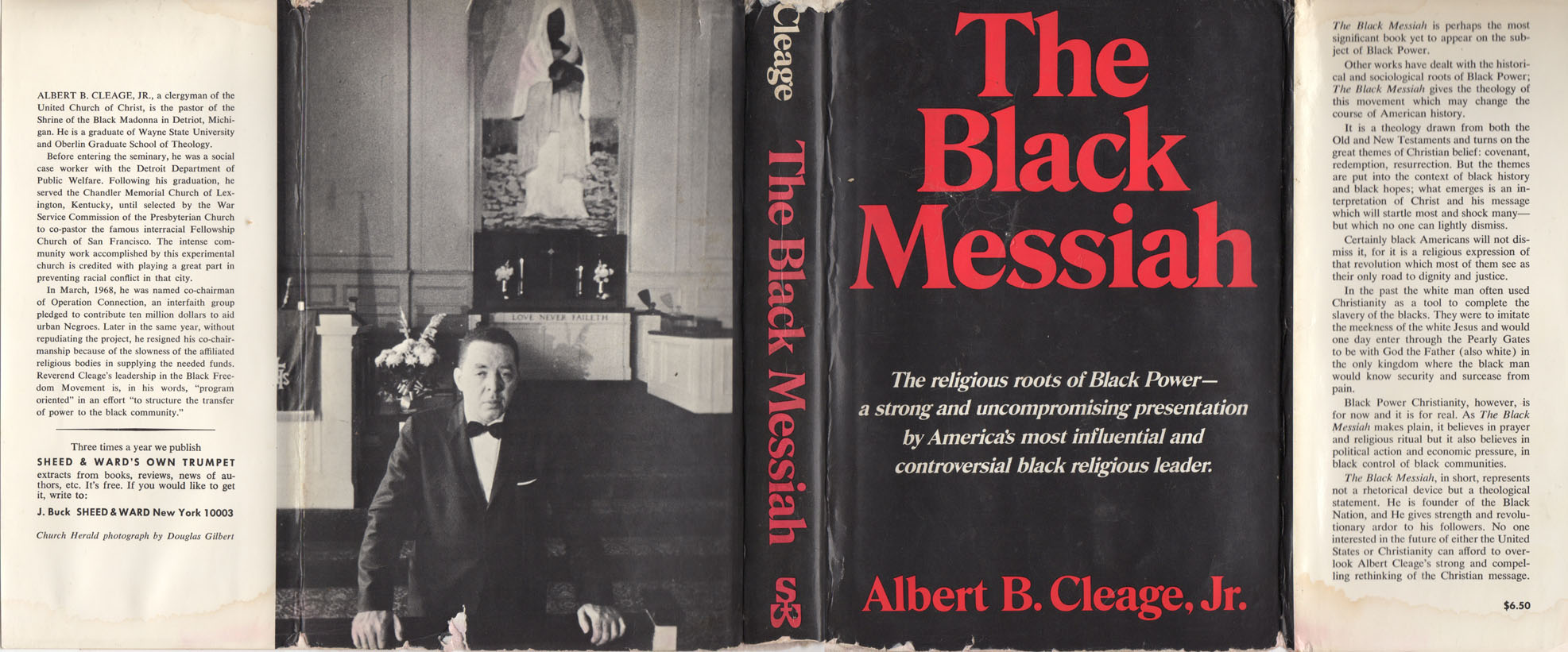

The Black Messiah was published in 1968. It was taken from sermons that my father made about black power and the black Jesus. I have all of those sermons am thinking about putting them online in the coming year.

I remember taking my copy with me when I went on my cross country bus/train/plane trip after graduating from Wayne State University. At the train station in San Francisco, as I waited to catch a train to D.C., a young white guy came up and started talking to me. He asked about the book but mainly he wanted to talk about waiting for his girl friend (or a woman he hoped would be his girl friend) coming in on the next train.

I also remember lending my mother-in-law my copy when she was visiting us in Simpson County, Mississippi. She didn’t finish reading it before she was scheduled to take a flight back to St. Louis. She carefully covered the book with a brown paper bag cover because she didn’t want anybody to see the cover.

Below, Rev. Albert B. Cleage, Jr., interviewed by Scott Morrison, Mutual News (New York: Radio Station WOR-AM, November 1968)

The Advent sermon below was preached on the first Sunday of Advent, November 27, 1966 by my father, Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr., who was later known as Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman.

First Sermon – Advent November 27, 1966

Second Sermon & notes – Advent December 4, 1966

The Star and The Stable – Sermon & Notes – Dec. 11, 1966

A Christ to Carol – Christmas Sermon & Notes Dec 22 1966