My Uncle Hugh Cleage playing tennis in the alley behind their house on Scotten. Seems to be quite dressed up for alley tennis. I don’t know who he is playing with.

This post continues a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life as part of the Family History Through the Alphabet Challenge.

This post continues a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life as part of the Family History Through the Alphabet Challenge.

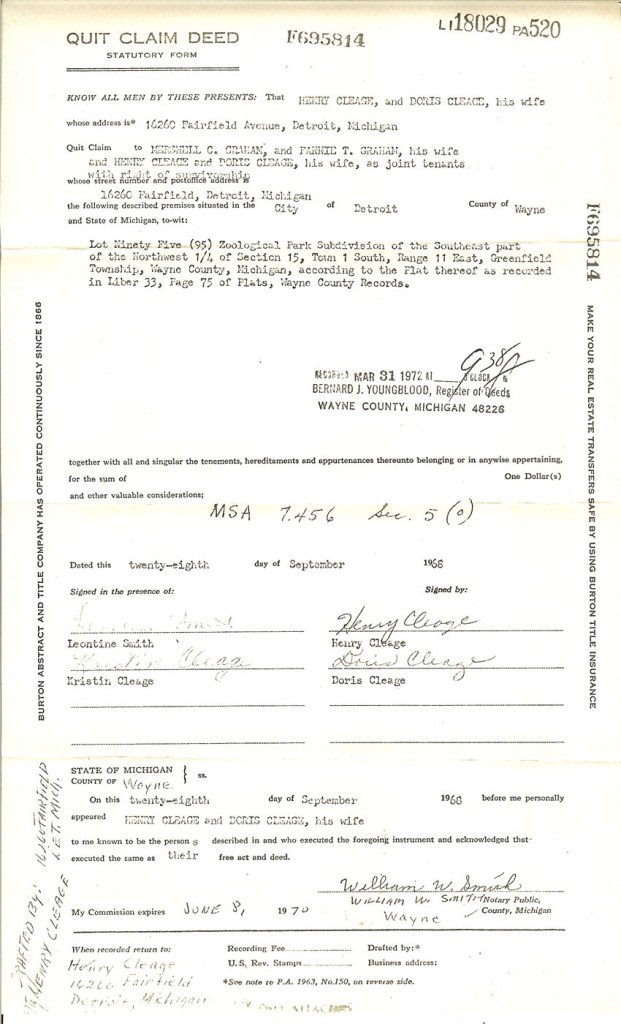

In the fall of 1968, Henry, my mother and her parents, Mershell and Fannie Graham, bought the flat at 16201 Fairfield. The Graham home on Theodore had been invaded, shot into and suffered an attempted armed robbery. Nobody had been hurt.

In the spring of that same year an insurance salesman was shot to death in front of our house on Oregon. The murderer cut through our backyard during his escape. Although nobody was home, my mother never felt the same about living there. They began to look for a flat to share.

I lived there from the fall of 1968 until I left home in the spring of 1969. My grandparents lived there until they died in 1973 and 1974. My mother and Henry were there until 1976, when they moved to Idlewild. My sister, Pearl, was a sophomore at Howard University when we moved and never lived there, although she came home for holidays.

The people in the photos are, starting upstairs and going from left to right – Henry looking firm, me the night before I left on my cross country tour, Pearl and my mother. Downstairs we have my aunt Mary Virginia who lived with her parents for some months, Alice (my grandmother’s youngest sister), my grandmother Fannie, my grandfather Mershell and my mother holding my daughter, Jilo. I got the idea for this photo house from a photograph I saw via twitter of a house in Detroit. You can see it at Detroitsees here.

The flat on Fairfield was kitty-corner from a University of Detroit field. The only thing I remember happening on that field while I lived there was a high school band rally with different bands doing routines throughout a Saturday. I remember staying up late working on art projects and catching the bus across the street to go to campus. Most of my memories are of returning to visit with my oldest daughter. I know that I didn’t spend half as much time as I could/should have spent talking with my grandparents when they were right downstairs.

This house is still standing and looking very good. You can see it on the corner in the street sign photo above. Although the hospital that used to be directly across the street is gone, the rest of the block is all there! Whooooohooooo!

You can see my mother and grandfather’s wonderful garden and read more about Poppy in “Poppy Could Fix Anything.”

Here is a photograph that has quite a bit of damage but still, it is one of my favorite pictures of my father. It was taken on the front porch of my grandparents house at 2270 Atkinson. Today would have been my father’s 101 birthday. He has been gone for 12 years.

My Grandmother Pearl Reed Cleage with a pot of tea, early 1940s.

My Grandmother Pearl Reed Cleage with a pot of tea, early 1940s.

My grandmother always had a pot of tea on the dinner table. My sister, cousins and I grew up drinking cambric tea. She made it for us by pouring a bit of tea in the cup and filling the rest with milk. The first time I had chai at an Indian restaurant, it took me right back to my grandmother’s cambric tea. When my daughters call to say they are on the way over, I put on the water for tea. Some drink cambric and some drink herbal. I still prefer cambric, without sugar.

More information about cambric tea and how to make it. It’s not that exact but for those who want the recipe click Mr. Peacock: The Comfort of Cambric Tea. Mr. Peacock seems to be pouring his tea from a chocolate pot, I notice.

These cows appear to be coming to the barn for milking. I believe they were on the farm my uncles Henry and Hugh Cleage had during WW2 as conscientious objectors. They had to milk a certain number of cows and they also had chickens. Henry was 26 and Hugh was 24 when they started farming. Hugh had a degree in agriculture from Michigan State University. They were conscientious objectors because of segregation and discrimination both inside and outside of the military. All of the training camps were located in the segregated south and the officers were all white. Henry wrote several of his stories while working on the farm, which was called “Plum-Nelly”, as in “Plum out the county, nelly (nearly) out the state”. Their farm was located near Avoka in St. Clair county, 62 miles north of Detroit.

___________________

I found an interesting interview with Ernest Calloway that reminded me of talking with Henry about being a conscientious objector below. You can read the full interview here – INTERVIEW WITH ERNEST CALLOWAY where he talks about other aspects of his long and interesting career as a labor organizer.

CALLOWAY: “Of course, in the first instance, I was a conscientious objector on the grounds of racial discrimination. I had the first…mine was the first case, you know. I refused to go into the Army as long as the Army was Jim Crow. And, oh, this was a battle for about two years. Over local draft board and state appeals board. I don’t think they ever actually settled the case…I think the case is still on the files somewhere…they just forgot about it. But I had pointed out on my questionnaire, the military wanted this questionnaire that I was given, the question was asked, “Are you a conscientious objector on moral grounds?” I scratched out the word “moral” and wrote in “special”, social grounds. And then I submitted a statement to explain that on the question on racial discrimination, under no condition did I feel like I was obligated, you know, to accept service in the Army. Of course, the chairman of the draft board thought I was kidding. And I insisted to him that I wasn’t kidding. I pointed out to him that if I was going to die then I was going to insist that it be on the basis of equality, you know. And, of course, finally, finally I did. Finally, the Communists wanted to take over the case in Chicago…then I get a telegram from Walter White of the NAACP that the NAACP would be interested in pushing the case. And White suggested that I contact the Legal Redress Committee there in Chicago, at the Chicago NAACP. And I went down to meet with the Legal Redress Committee which included such people as Earl Dickerson and some of the top black lawyers, you know, in the city of Chicago. But I found myself on the defensive because they were primarily concerned on…to determine what was my political background and my attitude about war in general. At that time, I was associated with the Keep America Out of War Congress which was headed, I think, by Norman Thomas… Norman Thomas, at the time…and a number of other liberal, socialists and liberals. And after about an hour and a half of this being on the defensive, trying to explain myself, I finally pointed out to these, to the lawyers, that I’m here at the invitation of Mr. White…that he asked me to come down and said the NAACP was interested in the case… that they would like to pursue the case of discrimination in the Army, but if you fellows are not interested in this, and I do not have to explain my political, you now…political motives and that sort of thing. That I can take care of myself, you know. I know what to do to take care of myself. Then I walked out of the room and, of course, one of the young lawyers followed me and he said he felt that I was right, that he would like to work with me on the case. And finally I was called into the office of the State Appeals Chairman who happened to be a Negro. And he wanted to know what was, and, of course, evidently a lot of publicity was being given to the thing, the national magazines, the black press, and that sort of thing. As a matter of fact, we had decided to form a little organization of our own, which included Sinclair Drake, who at that time was working with Horace Keaton on that Chicago, black Chicago project, Enoch Waters who was the editor of the Chicago Defender at the time, and a number of other youngsters; we were all youngsters. That was something like… Committee Against Jim Crow in the Army. And what we had discussed was the question if we could ever get a public hearing before the Appeals Board…we could put on a show, you know. And this was what we were after, you know. So, finally, the Chairman of the Appeals Board called me into his office. And he wasn’t clear about what in the hell this thing was all about. Of course, there were two technical aspects to it. Number one, the local draft board had refused to issue me, at that time…what was called Form 47, which is the form that is supposed to be issued to conscientious objectors to build their cases, you know. And, secondly, he had denied me the right to appeal from the decision of 1-A. I couldn’t appeal from this decision. Now we used to have more damn hassles, he used to, he called one day and he said, “You think you’re a smart nigger. But you think you’re gonna come in here and mess up this draft board, but you ain’t gonna do it to my draft board.” I said, “Well, you know, when I, when they, when I registered up here at the school, they told me I should look upon my draft board as a committee of friends and neighbors, and if I had any problems, I should discuss it with them, with the draft board.” And I said, “Gentlemen, I got a problem. I ain’t going into no damn Jim Crow Army. How we gonna work this thing out?” And, oh, we would sit there and argue like cats and dogs. And, of course, I had problems with my own organization, too, which was the redcaps union. The President of the Union, Thompson, felt that this would be bad for the union. Very bad for the union, you know. But the secretary-treasurer, we…I was very friendly with the secretary-treasurer… he felt I was not handling the thing properly…that I should keep from getting into arguments with these people and play it cool and that sort of thing. I said, “Well, John, you come on over to the draft board with me. Let me see how cool you can be with these guys.” And, you know, he said, “Mr. Calloway, let’s look at it this way.”…I think what they were trying to do is change my mind… he said, “Let’s look at it this way. Two neighbors are fighting, like cats and dogs, and so one neighbor’s house catches fire, what you do is stop fighting and help the neighbor put the fire out,” he said. “You understand…you understand what I’m talking about?” I said, “I don’t understand a word you’re saying. I’m not going in any Jim Crow Army. I don’t know who’s fire you’re talking about.” But, anyway, then I explained to the Appeals Chairman the technical problems and he said, “Well, hell, they can’t do that to you.” He said, “You have the right to appeal the 1-A and you have a good case. And I don’t know anything about this Form 47 for conscientious objectors, but I’ll go and get you one of those forms.” And he was a Negro, a Negro lawyer, and he said, “These people made me the chairman of the appeals board, but I been a black, too long…been a Negro too long, you know…I think you’ve done the right thing.” He said, “I’m going to get you a…this conscientious objector thing…and I don’t know, you talk about on social grounds, but it says something about moral. But you take as much time as you want, and you put your best foot forward.” And, of course, I did work out the statement and submitted it to the Appeals Chairman. And I haven’t heard from the case since. So, that’s been from 1940, this was, of course, all of this was before Pearl Harbor. All, most of this was before Pearl Harbor.”

This post continues a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life as part of the “Family History Through the Alphabet” challenge.

In 1969 I moved into my first apartment at 11750 N. Martindale and Elmhurst in Detroit. I was working at the Black Star Clothing Factory. To get to work I would walk a block down Elmhurst to Broadstreet. There I stopped by for a fellow sewer who lived on the corner. We would walk the 1.2 miles down Broadstreet to the Black Star Clothing Factory on Whitfield. According to Google Maps it takes 24 minutes to walk it. I think we were faster.

By the time the factory moved into the basement of the Shrine of the Black Madonna Cultural Center on Livernois, at the other end of Broadstreet, my walking partner was no longer working at the Clothing factory and I walked the 1.1 miles by myself. Google Maps says it takes 22 minutes.

I worked at sewing from March 1969 to November of 1969. I was not chased by dogs, accosted by maniacs, or any other disasters on my walks. The only outstanding event was that one day I bought an ironing board after work and carried it home the whole 1.2 miles.

View Broadstreet Avenue in a larger map

We would have cookies and coffee or tea. One time Winslow was making oatmeal, so I had oatmeal. They would tell me about how things used to be in Detroit, how it was living there now. And always had a good family story or two.

While working on this post I spent several hours “walking” through my old Detroit neighborhoods on Google Maps. Seeing the buildings that are gone, the ones that are trashed, the ones that are well kept and the ones that are boarded up, was depressing. When I do the next street, I will try not to go traipsing down side streets to see how the neighborhood is doing because most of my old neighborhoods are doing terrible. Here’s something good though, Anna said that one thing that made their house livable through all of the decline was that there was a park across the street so that she could look out of the window at trees. The park seems to still be in good condition.

This post begins a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life, as part of the “Family History Through the Alphabet” challenge.

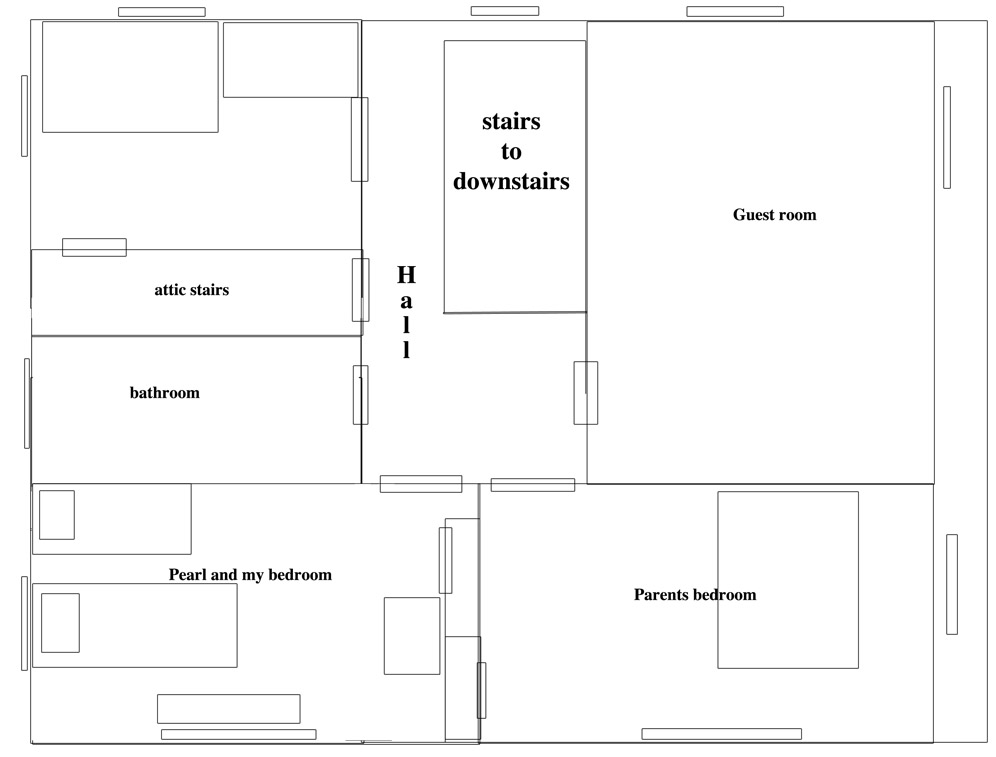

I will start with Atkinson in Detroit. The layout of the house isn’t exact as far as scale, but it is as close as I remember it. The last time I was in this house was in 1953. I was 6 years old.

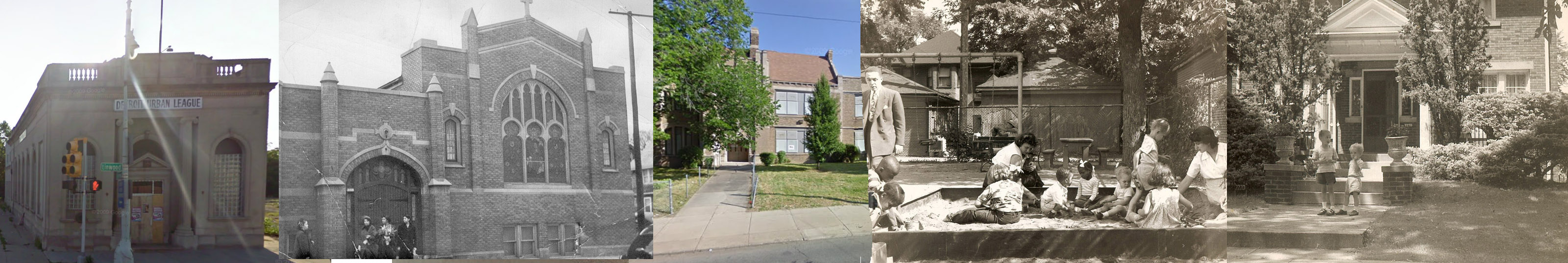

In 1951, when I was four, my father received a call to St. Marks Presbyterian church in Detroit. We left Springfield, Massachusetts and moved into 2212 Atkinson, down the street from my paternal grandparents who lived at 2270 Atkinson. St. Marks was located a block away, in the other direction, on 12th Street. The 1967 Detroit riot started a block from the church.

I attended kindergarten at Brady Elementary School. I was eager to start school and there were no tears or fear. I remember a cartoon with the white corpuscles battling it out with germs, painting everyday on the easel. I don’t remember my regular teacher but a substitute teacher stays in my mind. She was short and wore her white hair piled high on top of her head, kind of like a wedding cake. I remember her as wearing a purple dress and being mean.

I walked to school by myself – two blocks down Atkinson, a short distance on Linwood to the light and a long block next to Sacred Heart Seminary. Usually there were no other walkers because I was late. I especially remember being late when I started first grade and came home for lunch. I must have been a slow eater because I was late just about everyday. I didn’t mind walking alone but I didn’t like being late. One day I was coming home for lunch and as I was passing the neighbors house, two girls around my age, were outside with their dog Duchess. The dog came up growling and caught my wrist in her mouth. They just stood there and I just stood there. Soon my mother came out and rescued me. She said she heard me calling her but actually I hadn’t said a word. My father kept a big stick by the door to hit Duchess with when she ran out to attack.

Pearl and I shared a bedroom. For much of the time she was still in her crib. She was 2 or 3 when we moved. She would tell me stories about Oliver Olive and a tear on the wallpaper right over her crib that we called Tecumseh. Later, after I learned to read, I taught Pearl to read when we were supposed to be going to sleep. We had a little table over by the window and the street light gave us enough light. Out of our side window we would watch our neighbors, the two girls with the mean dog, playing in their fantastic attic playroom. We had to go to bed at 8pm all year long, light outside or not. They did not. When it was light outside and I was in bed, I imagined pictures from the folds in the curtains.

We were not allowed to play outside of the backyard, even though I was walking alone blocks and blocks through rain and snow and sleet to school. There was a large screened in porch on the back of the house but we couldn’t play on it because it never got cleaned off and we would have tracked dust and dirt into the house. It was a really nice porch and I longed to play on it. But I didn’t. My mother bought us some easels and paint because I liked to paint at school so much and I used to paint in the basement when she was washing or hanging up clothes.

We didn’t have a car and we took the 14th street bus to go downtown and to go over to my grandparents on the east side on Saturdays. There must have been a streetcar around there too because I didn’t get sick when we rode the streetcar but when we took the bus we sometimes had to get off and walk because I would be getting ready to throw up. My mother’s bank was on Linwood and I remember the black and white squares on the floor that my sister and I used to walk around on. Down the street was a Dime store where we use to buy tiny little dolls with tiny blue bath tubs and a comparatively big bottle. There were a lot of little toys but that is all I remember buying. The bank is now deserted and the rest of the block is empty.

During first grade I told my mother I didn’t feel good one morning. She thought I was just trying to get out of school, although I don’t remember trying to get out of school, and made me go. By the time I came home for lunch I had a fever. It turned out I had pneumonia and missed half of that year of school. I was moved into my parents room and I guess they moved to the guest room. My uncle Louis, who was a doctor and lived down the street at his parents house came by to see me everyday. I remember him singing “Oh if I had the wings of an angel over these prison walls I would fly…” as he came up the stairs. For a while I had to use a bedpan and I remember holding on to the wall for support when I finally was allowed up. By the time I got to go downstairs it was like being in a new house it had been so long since I saw it.

In 1953, my father was involved in a church fight and led a faction of 300 out to start another church which became Central Congregational Church, then Central United Church of Christ and finally The Shrine of the Black Madonna. My sister Pearl and I spent that summer with my mother’s parents on Theodore. My father stayed with his parents on Atkinson. In the fall we moved to a new parsonage on Chicago Blvd.

I found this description of 2212 Atkinson online. Built in 1921, it is a single family 2,222 square foot residence. Has two stories with a basement. (I recall an unfinished attic.) It has one full and one partial bathroom. The heating is by hot water. (I remember the radiators) The exterior walls are brick and there is a fireplace. (The fireplace was in the room designated for the use of the church only.)

View Atkinson Street Detroit, Michigan in a larger map

Other posts that relate to the house on Atkinson and St. Marks;

Dinner Time

Ghost photo of Atkinson then and now

A Day in 1953 Merges with a day in 2011

Politics