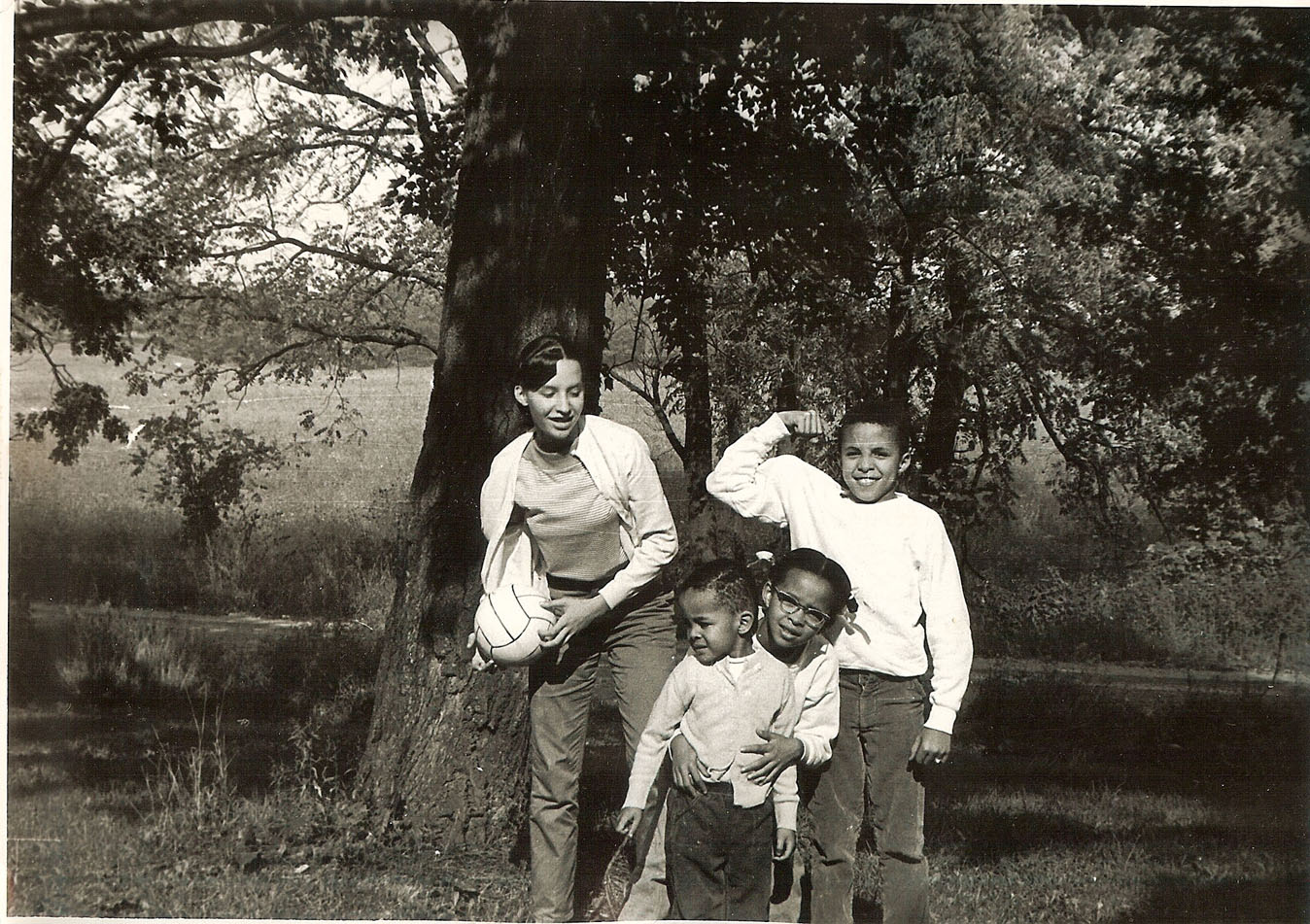

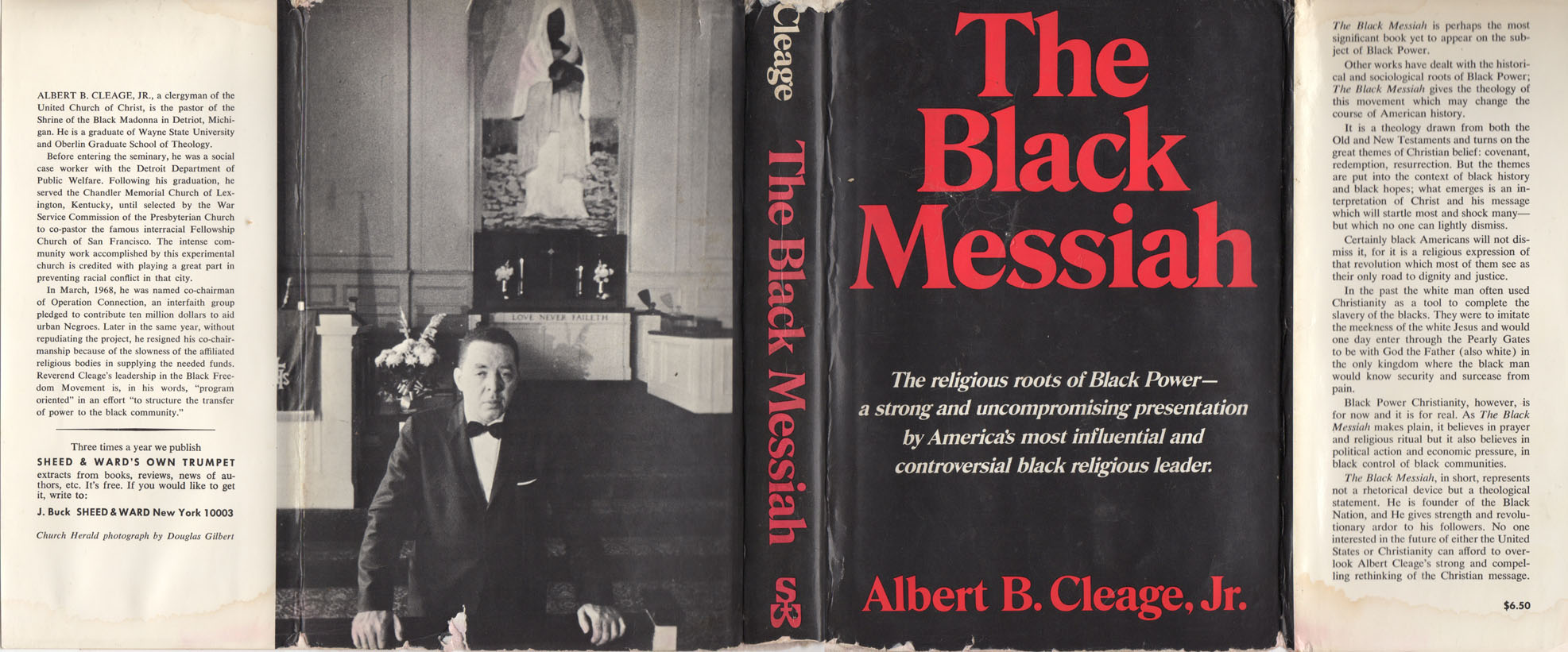

Taken at Old Plank about 1963. Me with my cousins, Blair, Jan and Dale. They seem to be trying to pose for the photographer while I am about to cause trouble with that ball. I was a senior at Northwestern High School in Detroit. Old Plank was 30 minutes outside of Detroit near Wixom. We had 2 acres with a big house and although there was talk of moving there, we didn’t. We went for weekends to get out of the city until 1967, after the riot when the printing business lost the businesses that burned or left. At the same time, a man bought the barn and let his chickens and hogs run lose. Before he and Henry came to blows, they sold him the house.

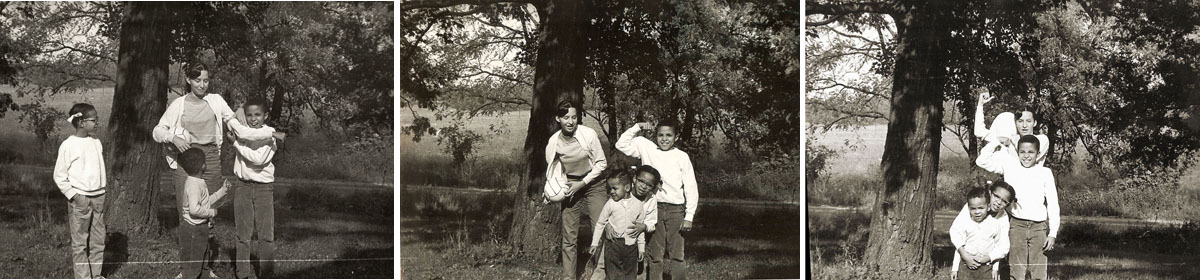

There were two more photographs taken that same day. I think they were taken in the order shown below. My uncle Henry took the photos and developed them at the print shop that he and Hugh ran at the time – Cleage Printers.