S is for Sixth Avenue, Mt. Pleasant, SC

This post continues a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life as part of the Family History Through the Alphabet Challenge. I am remembering living at 160 Sixth Avenue, Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina. We lived there for one year, I was 29 and Jim was 30. We had two daughters – Jilo, four and Ife, almost two. Jim was hired as director of the South Carolina office of the Emergency Land Fund, a group trying to stem the lose of Black Land. We moved from Atlanta, GA to Mt. Pleasant, SC. in October, 1974. His office was in Charleston. We were less than ten minutes from the ocean. For the first time, I was a “housewife”. I was a volunteer teacher with the children’s art program at the Charleston Museum. I learned how to drive. Got pregnant with our third daughter, Ayanna. In early November of 1975 the office was closed and we moved to Simpson County, Mississippi.

Memories:

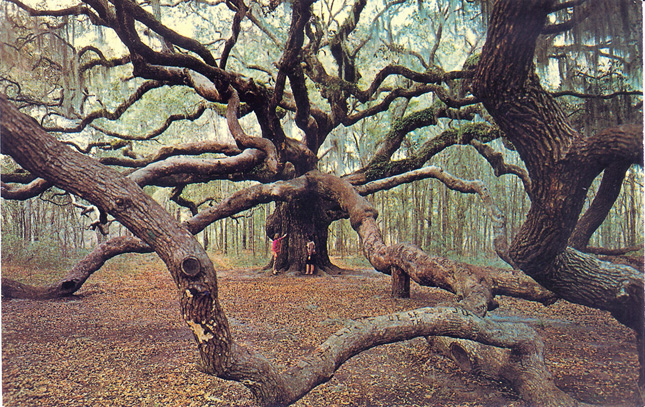

The man plowing the field next to our house with a mule. Spanish moss in the oak trees. The Angel Oak, over 1,000 years, with branches on the ground as big as tree trunks. The local people’s way of talking. Getting shrimp and flounder fresh off the fishing boats. Swimming in the Atlantic. Picking up a bucket of sand dollars. Celebrating Kwanzaa. The family with 5 daughters next door, and next to them, a family with 2 boys and 3 girls and all the children in the three houses playing together in spite of the age differences. Buying day old chicks and all of them dying within a month. My great garden in that silt. Having almost no outside of the house involvement. Feeling outside of the ‘world”. Jilo going to church with the kids next door. Jilo and Ife going trick or treating in their jackets because it was so cold. Taking the bus to Michigan to visit my family, with the kids. Going to St. Louis in the VW bug for our first William’s family reunion. Visitors from Atlanta and Detroit. The end of the War in Vietnam.

October 8, 1974

Hello Mommy and Henry,

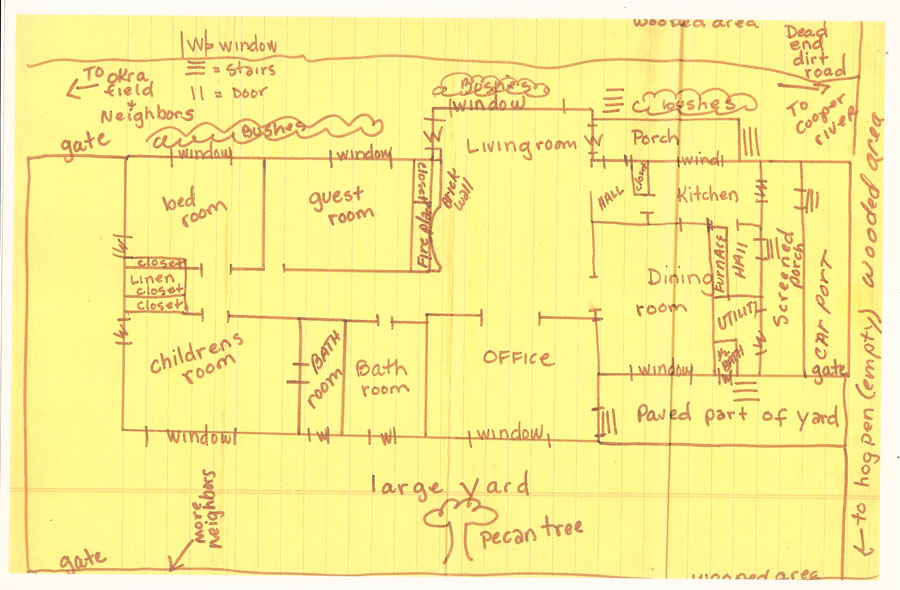

Well, everything here is moving right along. Jim still likes his job. The house is pretty well cleaned up and unpacked, but I’ll be glad when we get the furniture from Nanny and Poppy’s. We would like the dining room stuff too, if it’s available. I have enclosed a layout of our house and some postcards of our scenic view (smile) The only bad part is – the car’s broken down. After Jim drove it from Atlanta, it broke down. He is going to get a used transmission for it. I hope that does it because nothing is within easy walking. There’s a bus into Charleston, but it’s a good walk. I hope you all will be able to get down to visit this winter before we’re back to our normal living conditions. (smile). I read this article in McCall’s telling parents not to worry about their weird kids because around 30 they settle down.. Can this be true???

I found where the people had their garden and plan to put some lettuce, greens etc. in next week. I will be glad when we can meet some people! More soon – WRITE!

A note from Ife (scribble scrabble)

P.S. I may come for a week early Nov. 21, more later.

Love,

Kris

For more about the Angel Oak, go to this post – Trip to Jekyll Island

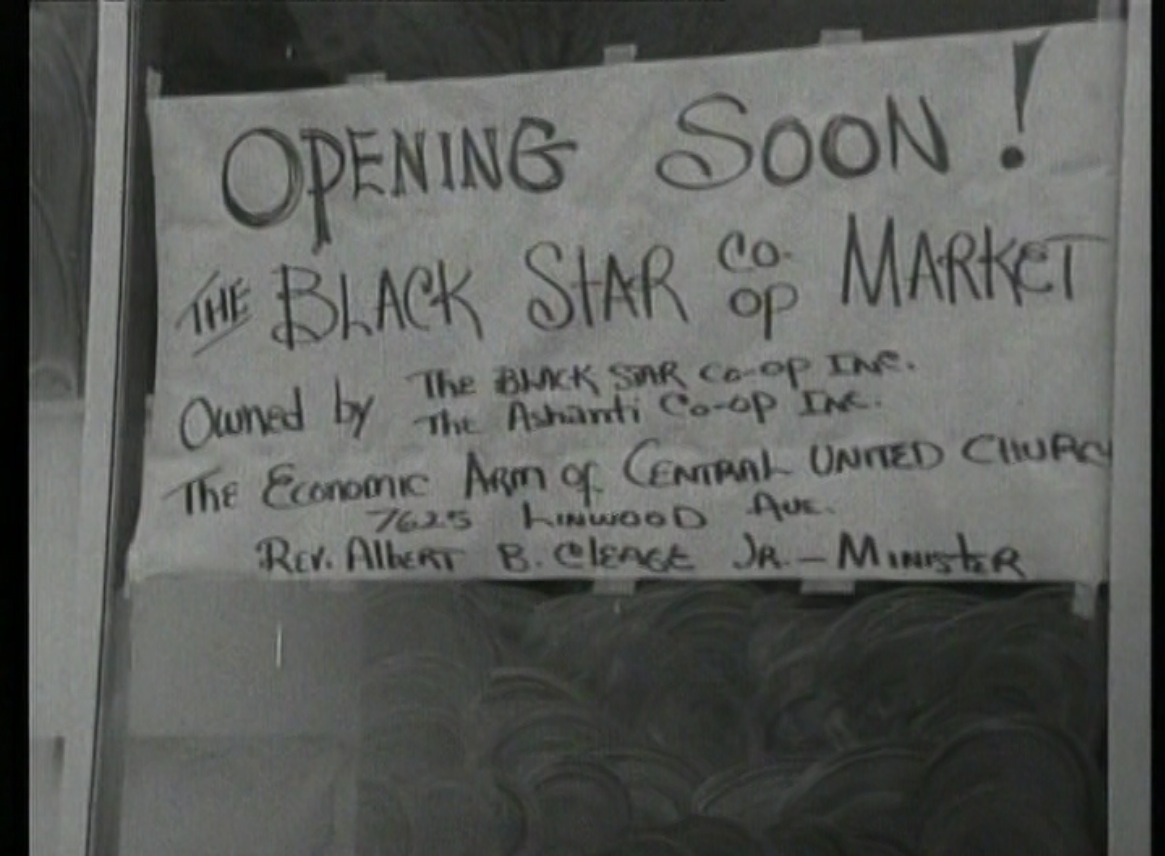

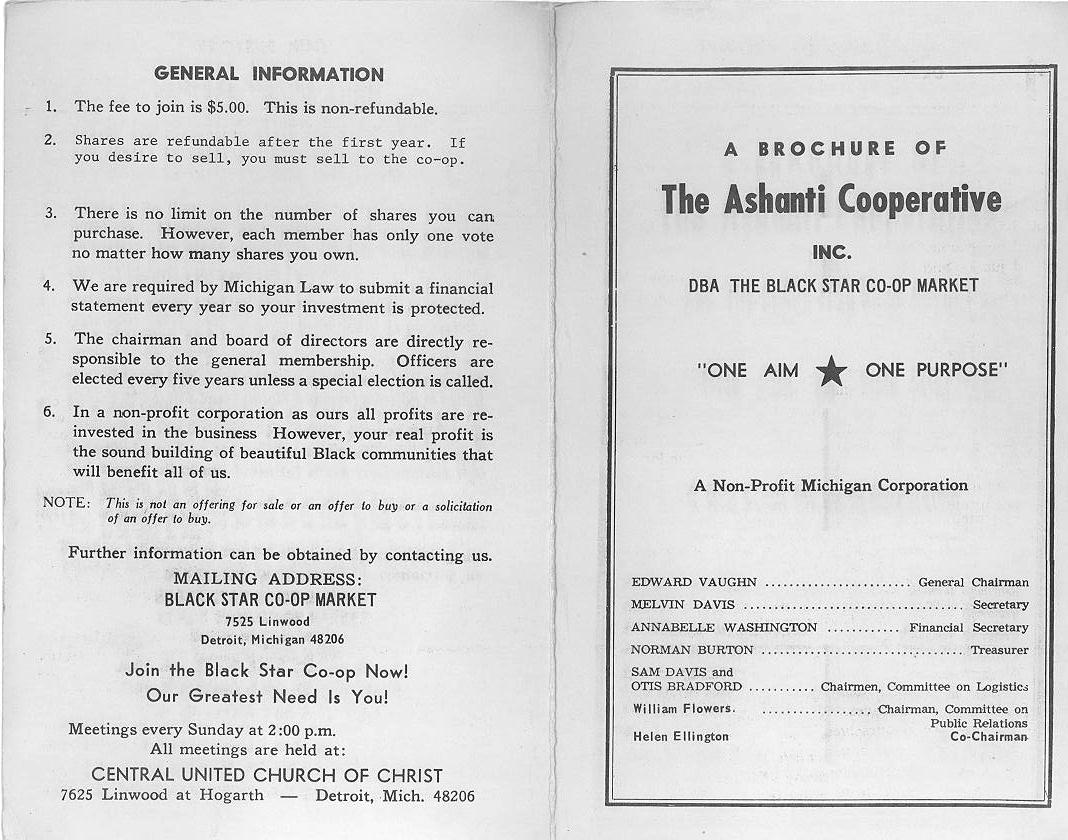

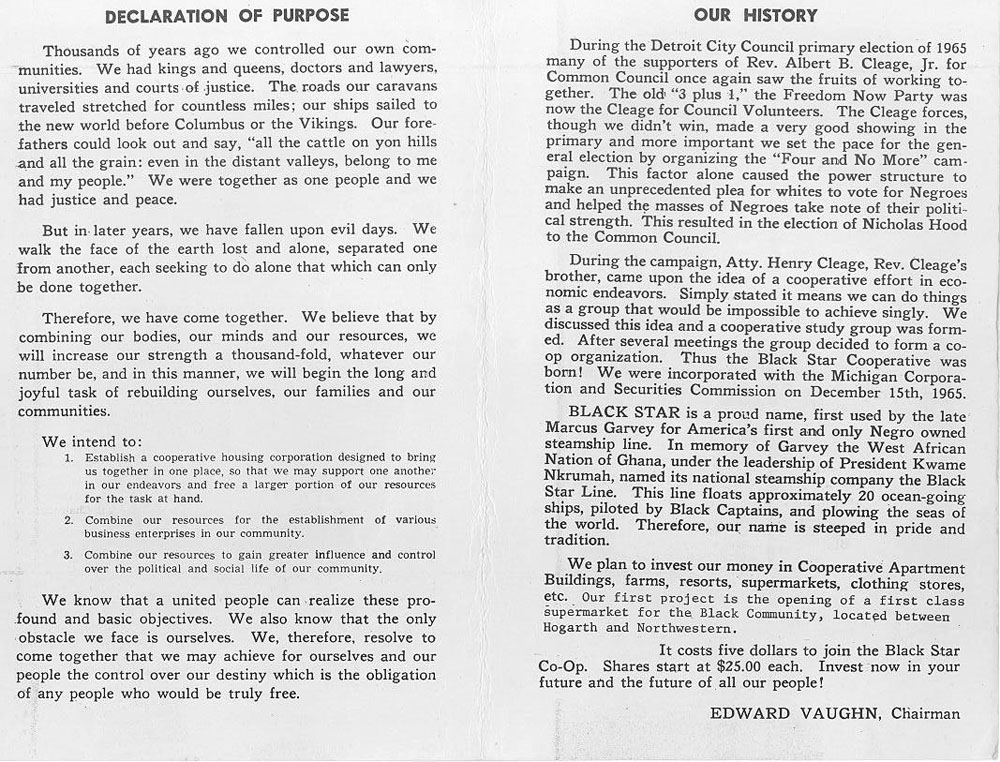

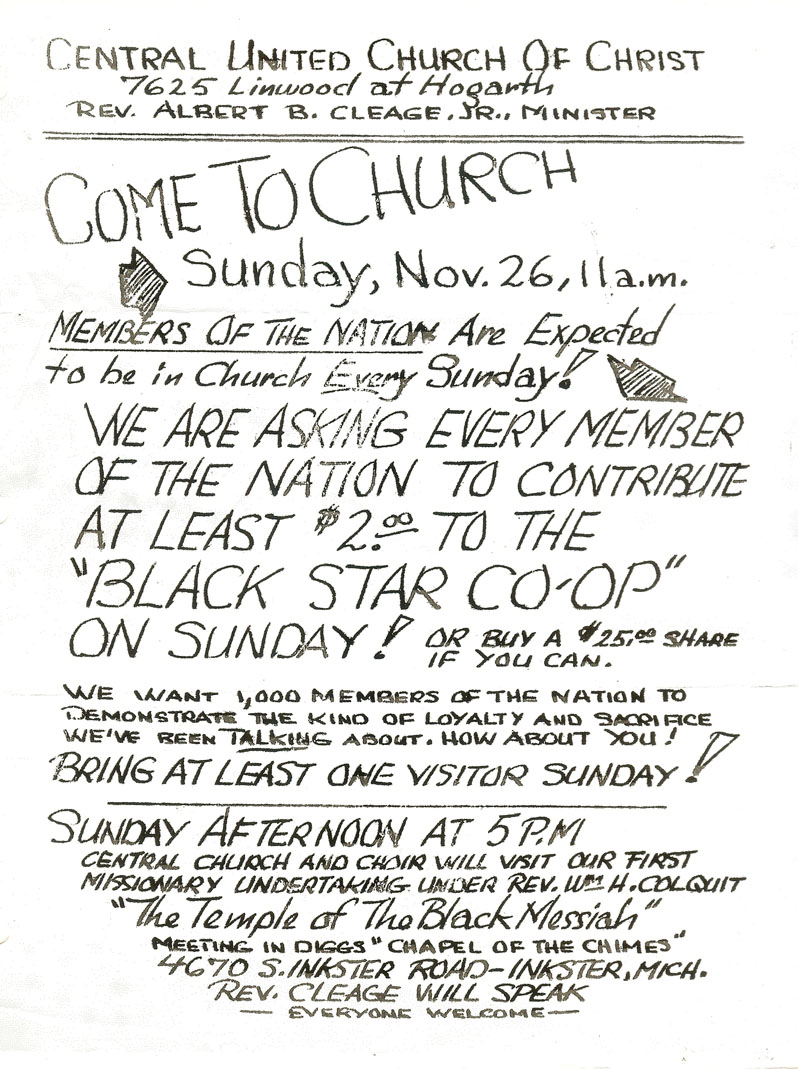

The Black Star Co-op – 1968

In 1965 the idea of the Black Star Co-op was born at Central United Church of Christ. In 1968, the year after the Detroit riot, a grocery store was opened a block from the church. Due to a variety of reasons – inexperience of management and staff, costs of keeping enough stock, high prices – the store did not last long. Later the church operated a long running food co-op. Several people would go down to Eastern Market early Saturday morning and buy produce which was shared by everybody who paid $5 that week. There was no overhead and no paid staff. Later the church had a farm in Belleville, Michigan and the food for the co-op came off of that farm. Below is a short photographic story of the Black Star Market.

To read more about the church and the street it stand on, click on these links: “L” is for Linwood (About the street of Linwood), “H” is for Linwood and Hogarth (About the church).

R is for Route 1 Box 173 & 1/2

This post continues a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life as part of the Family History Through the Alphabet Challenge. This week I remember living on St. John Road in Simpson County, Mississippi. However, since I already have an “S” street coming up and I needed an “R” street, I am using our mailing address, Route 1, Box 173 1/2, Braxton, MS. I don’t have a photo of our mailbox so I am using a return address from a letter I wrote back then.

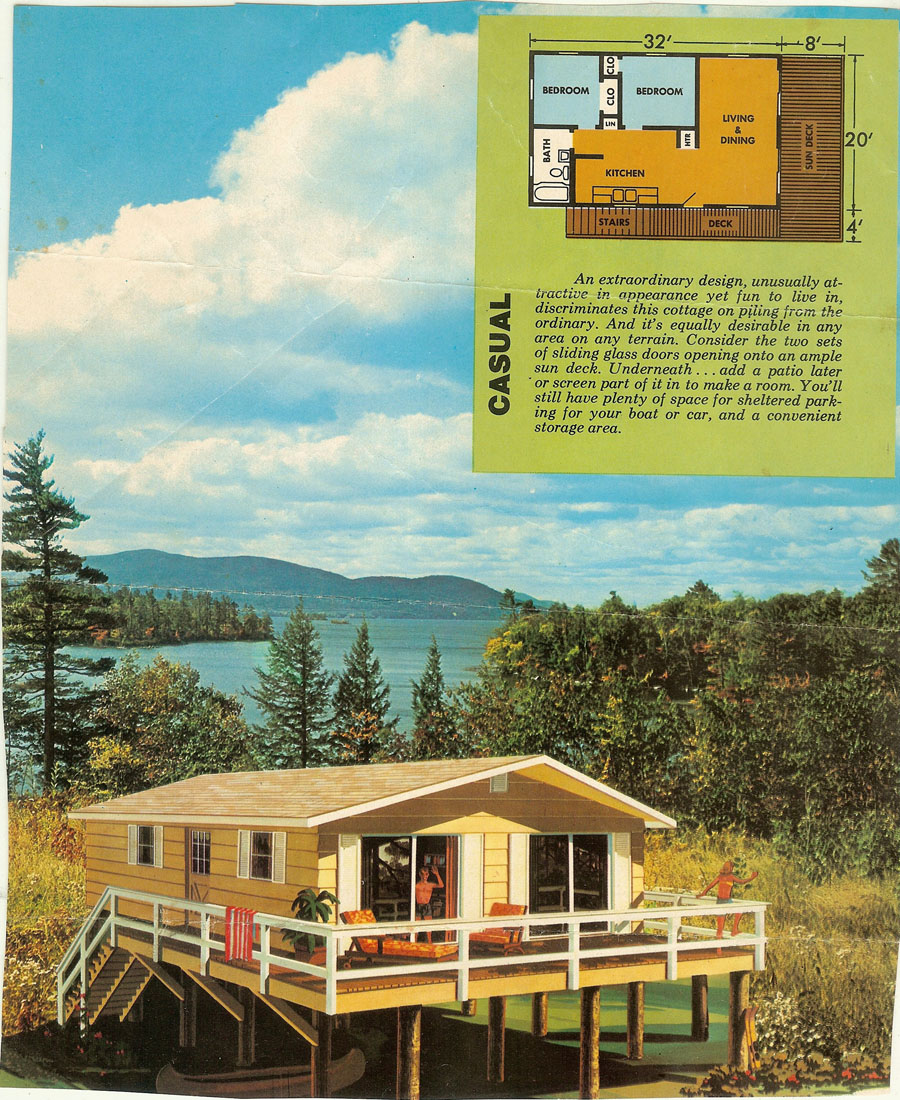

We moved to Simpson County, Mississippi in the fall of 1975. I was pregnant with our third daughter who was born April 12, 1976 at the home of our midwife. We had never lived in the real country before this move. Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, outside of Charleston, was the closest we had been. My husband was working as an organizer with the Emergency Land Fund (E.L.F.), a group to help black farmers save their land, which was being lost at an alarming rate. We first lived at Rt. 1 Box 38 where the Emergency Land Fund had a model farm. Maybe I should say we helped setting up a model farm, complete with rabbits in the pen and tomatoes in Green houses and our own milk goats and chickens. When the Emergency Land Fund wanted to move us to the Mississippi Delta to run a soy bean farm, we opted to stay in Simpson County and Jim quit working for E.L.F. We had to move from the farm and so bought our first house and 5 acres several miles away. The house was a Jim Walters House that had been built by former volunteers to the Voice of Calvary Church in Mendenhall. You can buy the house in various stages of completion and the more you finish yourself, the cheaper the cost. It was from the plans in this picture. Unfortunately there was not a big lake in the yard and there was no danger of flooding. We were much more likely to have a tornado come through and that caused me many anxious nights as storms rolled through and we were 10 feet off the ground. There was indoor water for the bath and the kitchen sink but there was no indoor toilet. There was an outhouse outback. There was electricity and my husband, Jim, hooked up the washing machine. It wasn’t too hard to run pipes since they were all exposed under the house. That caused problems when we forgot to drip the water when temperatures dropped. Eventually we did get an inside toilet but it was several years coming. Three of my six children were born in Mississippi.

A letter I wrote home from Mississippi not too long after we moved in.

January 19, 1977

Dear Mommy and Henry,

Here’s your late gift box. I’m sending some books – not to keep but to read (smile). The Tatasaday book should be read with the Iks in mind. I hope the hats fit and the cake is o.k. It didn’t come out as good as the last but i figured i’d better send it on.

It snowed here – about 2 1/2 inches and it’s still on the ground! Boy oh boy – first time the temp went to 6 degrees here, ever. And the most snow since 1958. Jilo’s school has been closed 2 days. We went for a walk in the woods yesterday. It was nice. Jim’s been going out with a neighbor down the road to cut pulpwood. Do you have those big trucks up there? He likes it fine. But it keeps him busy and working nights.

The goats are fine. 1 month until 3 more are due. The chickens are giving us 6 to 9 eggs daily with 13 hens. Still 4 aren’t laying i think. The midwife’s parents came over and told me to keep them locked up until noon and keep food and water there and they’d probably start up – and they did. The garden isn’t started – luckily for it.

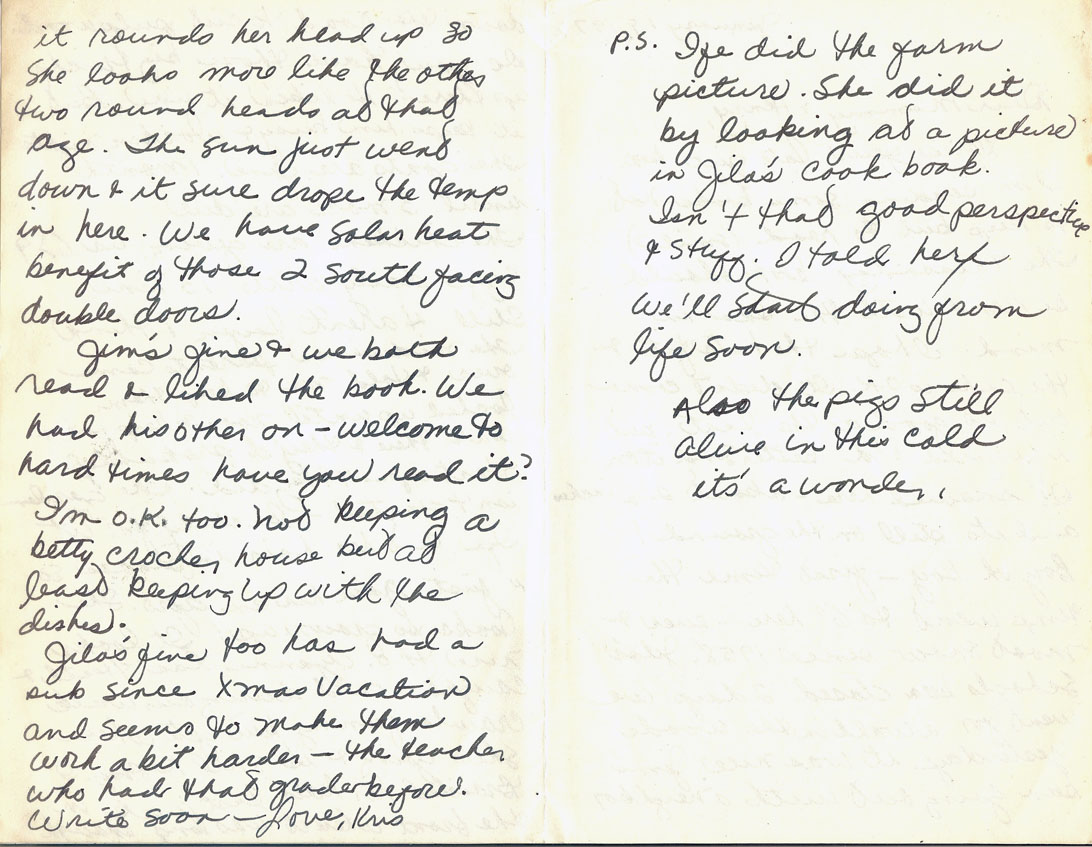

Ife cut her hair in places so i just gave her an afro. She looks so grown up! It looks nice though. Ayanna has 4 teeth and crawls funny but gets where she’s going and is still happy. I braided her hair last week in the front where it was long enough. it rounds her head up so she looks more like the other two round heads at that age. The sun just went down and it sure droped the temp in here. We have solar heat benefit of those 2 south facing double doors.

Jim’s fine and we both read and liked the book. We had his other one – Welcome to Hard Times – have you read it? I’m ok too. Not keeping a Betty Crocker house but at least keeping up with the dishes. Jilo’s fine too, has had a sub(stitute teacher) since Christmas vacation, She seems to make them work a bit harder – the teacher who had that grade before.

Write soon – Love Kris

P.S. Ife did the farm picture. She did it by looking as at a picture in Jilo’s cook book. Isn’t that good perspective and stuff. I told her we’ll start doing from life soon.

Also, the pig is still alive in this cold. it’s a wonder.

For more about living in Mississippi, including goats, killing chickens, heating with a wood stove, midwives, friends and work shoes read these posts.

Three Hats

These are friends of my grandfather, MC Graham (Poppy). I used this photograph before but never as the featured photo. I thought the bowler hat theme was perfect for this. I don’t know who they are. The photograph was probably taken between 1917 in Montgomery before my grandfather married or 1919 in Detroit. Unfortunately it’s undated and unidentified. I am going by the clothes my grandfather wore that day and in other photos that are dated.

My grandfather and unidentified friend.

This photo is un-photoshopped. I couldn’t get the woman’s face right so I just included it as is. You can see more of the coat in this one. We are left to guess at the dress underneath.

Mignon Leaps

Q is for a Quiet street – Water Mill Lake

This post continues a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life as part of the Family History Through the Alphabet Challenge. Amazing I know, but Q is a letter I do not have a street for. Someone suggested I do “A quiet street” for Q so this post will be about the house on Water Mill Lake, the quietest place I ever lived. Except for that one night something was killing something out in the forest. And there were those duck feathers strewn around the pathways as the ducks down the road disappeared, one by one.

In 1976, soon after the birth of my third daughter, my mother and Henry moved from the house on Fairfield in Detroit to the house on Water Mill Lake in Lake county. Water Mill is a much smaller lake than Idlewild and is less than a 5 minute drive away. Lake county is a 4 hours drive from Detroit. The house was separated from it’s lake front by a dirt road. In the back, through trees and underbrush, was the Pere Marquette River. This house was in the Manistee National Forest. Houses were few and far between. My mother and Henry planted a wonderful organic garden, fished and froze the bluegills they caught for winter eating and installed a wood furnace to cut down on the heating bill. I would go up for several weeks in the summer during June, with my children after the Williams Reunion in St. Louis. We lived in Simpson County Mississippi at that time.

In 1978, shortly after the birth of my fourth daughter, my mother was diagnosed with uterine cancer. She had noticed bleeding but ignored it for too long and after several years of treatments that took them to Detroit far too often, she died in 1982. Just after the birth of my son. Henry continued to live there by himself, seeing his brothers, sisters and friends who came up to Idlewild in the summer. In the winter there weren’t too many visitors.

In 1986 we moved to the house on Idlewild Lake. Of course Henry became part of our life, eating dinner with us often, us visiting him and him visiting us. He contributed lively discussion, the same kind I remembered from my growing up years, to my children’s growing up. In 1996, shortly after being diagnosed with liver cancer, Henry died. He left us his house. We rented it out for several years. Our oldest daughter lived there when she returned to Lake County as Assistant principal of the local high school.

In January of 2005, with only one of the children left at home and serious foundation problems with the house on Idlewild Lake, we decided to move to Henry’s. We added a few windows and had the attic turned into another bedroom. We had to replace the septic system which took out a few trees behind the garage so we put a garden in back there. We bought the lot next door at an auction. There were deer in the yard, racoons trying to get into the garbage cans. Racoons are so much bigger then they look in children’s picture books. At one time there had been a lot of people who came to that road to fish but the owner of the property had posted it so there was not much traffic on the road and not many people coming to fish. The lake was too small for jet skis and speed boats, that was nice. We had to walk up to the corner to get the mail because the mail man didn’t come down that road to deliver. There were only 4 houses on the road and only ours and one at the corner were occupied all the time.

Our third daughter moved home after graduating from University of Michigan while searching for a job. The spring of 2005 another of our daughters and her family moved to Idlewild on the way from Seattle to wherever she found a job, which turned out to be Atlanta. During that summer we had visits from the other children. They stayed between our house and the old house on Idlewld Lake. It was good to have everybody close by again. In the fall of 2005, our youngest son moved to Atlanta to work with AmeriCorps, then the second daughter moved to Atlanta. Somewhere in there the third daughter moved to Indianapolis for her new job. Our two elderly dogs died. We were down to one cat. My husband and I were alone for the first time in forever. It was wonderful. It was peaceful.

In 2006 our daughter who lived in Detroit moved to Atlanta. In the summer of 2007 we helped our third daughter move from Indianapolis to Atlanta and decided to look around and see what we could find because it seemed to make sense that we all settle in one place to be both support and company for each other. We found the house with the solarium (which is on Venetian so I will be writing about it in a few more posts) and that decided us. Just as the Michigan housing market went downhill, we sold the Water Mill house and bought the one Atlanta just before that market went downhill. We sometimes talk about how we could have done it differently and held on to that house in Idlewild while spending some of the winter months in Atlanta. Moving made sense but I really miss being on the water and being out of the city.

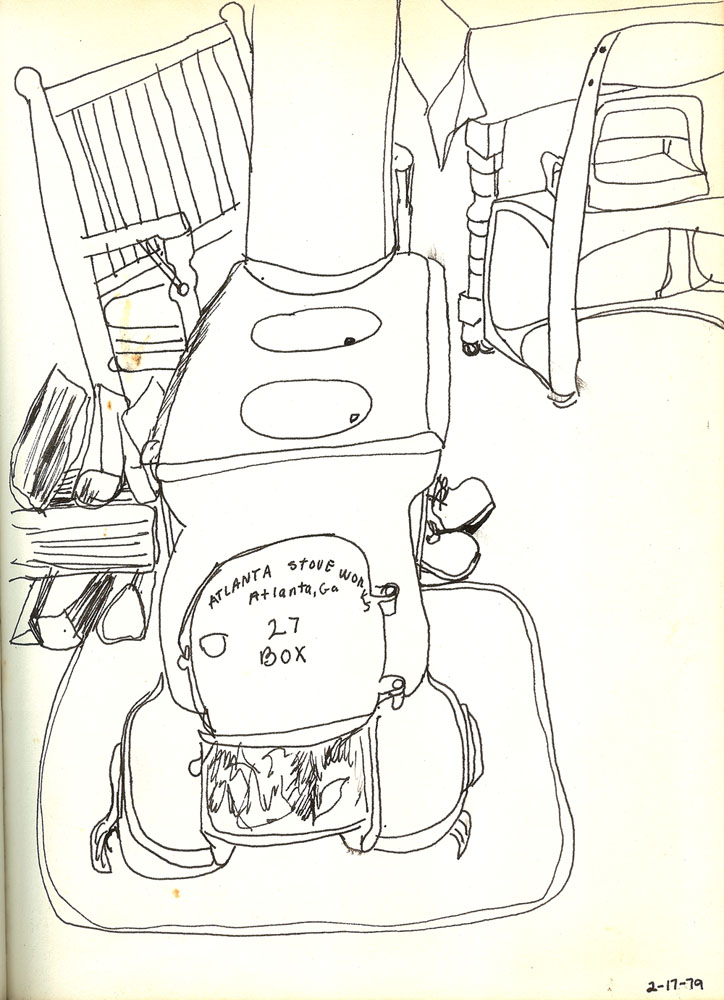

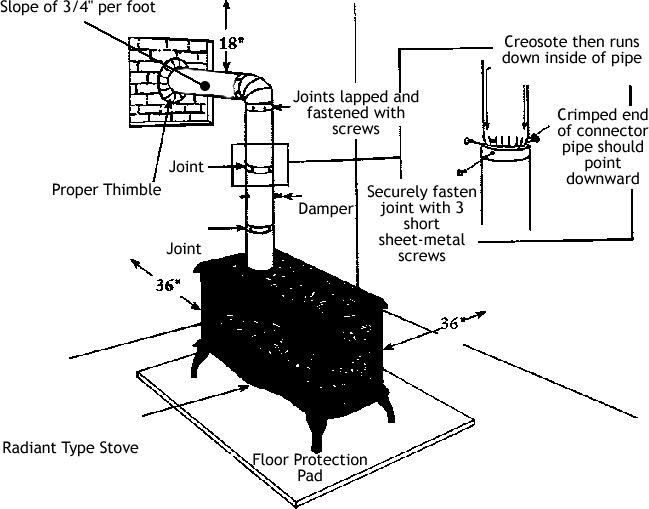

Burning Wood

We used this to heat our small house in Simpson County, Mississippi. We used a pickup or two of wood for the entire winter. Sometimes I cooked on it if the bottled gas ran out. It was also great for drying diapers hung on lines across the room.

For those who haven’t used a wood burning stove like the Atlanta Stove Works we used, here is a diagram of safety measures. When we first started, my husband didn’t realize why the stove was set out so far from the wall and moved it closer. Luckily we just ended up with a scorched piece of paneling and not a house fire.

This was not a very efficient furnace. It took enormous amounts of wood. My husband spent much time cutting, hauling and splitting wood all winter long. Because he worked long hours from spring through fall it wasn’t possible to get all the wood needed during the snow free months. Luckily we lived in the Manistee National forest and there was plenty of wood around. A few times we burned coal. It burned hot but it was so dirty. Soot everywhere. Up and down the stairs all winter long to keep the fire going.

The cook stove we used for several years in the Idlewild Lake house was a combination of wood burning on one side and electric on the other. The only photo in my collection and the one above. The stove was on it’s way from the kitchen to the garage after the insurance inspector said it didn’t meet guidelines for safe use.

When we moved to the house on Water Mill Lake we had a wood furnace like this one. It was very efficient and could burn one load almost all day. That meant a bit less wood (by now we also had a wood splitter) and a few less steps up and down the stairs to keep it going. Wonderful!

When we moved to the house we now live in in Atlanta, Ga we found this stove already in place. The house is passive solar and has a berm against the north wall and a wall of windows on the south side. We burn wood to take the chill off in the winter if there is no sun out. If the sun is out it heats all by itself. We also have an gas furnace we use only rarely when we don’t feel like building the fire. We are back to a couple of pick up loads a winter and with all the trees that topple over in Atlanta we have no lack of wood available. If only we’d brought the wood splitter.

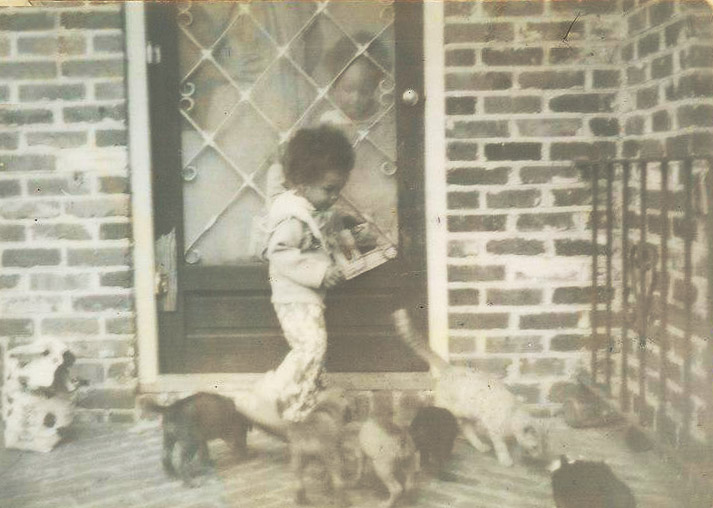

Chickens in Detroit 1919

“P” is for South Payne Drive

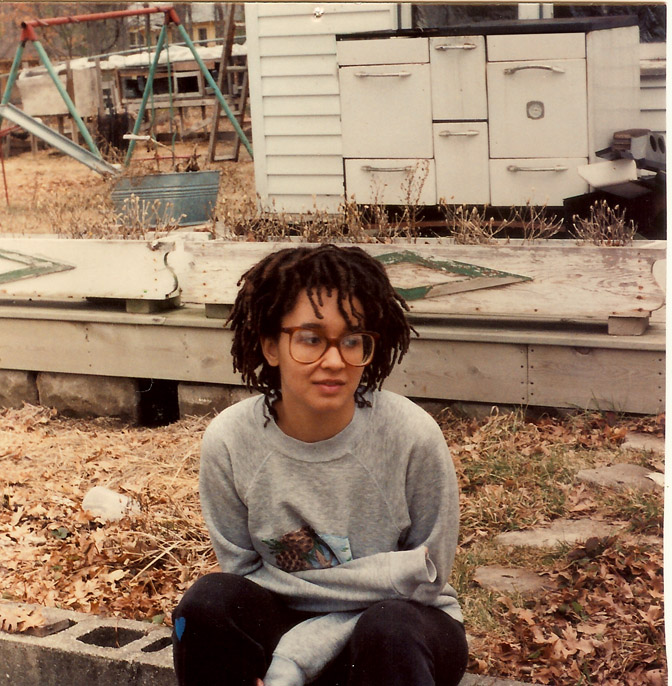

This post continues a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life as part of the Family History Through the Alphabet Challenge. This week we go to S. Payne Drive in Idlewild, Michigan. We moved there in August of 1986 when I was 39 and lived there until January of 2006. Almost 20 years. The longest I have lived anywhere.

When I was growing up we used to go to my Uncle Louis’ cottage in Idlewild. My cousin Barbara and I fantasized about riding our bikes from Detroit to Idlewild and living in a vacant cottage. Our plan fell through because we never came up with the agreed upon $10.00 each. This is still my favorite house of all I have lived in. If only the children and grandchildren had been closer, we would still be there.

Some of the things I remember about living on S. Payne Drive are – the lake in summer for swimming and in the winter for skating. The stone fireplace. The wood burning/electric stove we cooked on for several years before the electric side went out. Cabral joining the family the year after we moved in. The unacceptable local schools and our journey into homeschooling. The years the uncles, aunts and cousins were at their own places in the summer and sometimes the winter. Story rounds and the AOL homeschooling area and my addiction to the computer. Years without television. Dollhouse Doll Ville. Delving deeper and deeper into my family history. Track and basketball and Interlochen. Tulani’s dog sledding. The children growing up and moving out. When you have 6 spaced out 2 to 4 years apart it seems an endless process but end it did.

I remember times when family came from far and wide to be together. The grandchildren being born. My husband Jim traveling hours to work for the Michigan Dept. of Transportation in Ludington, Traverse City and points north. Winter layoffs. His years on the Idlewild volunteer fire department. The short periods of time I worked at the Baldwin and Idlewild Libraries. Our yearly Community Kwanzaa Celebrations. Icicles hanging from the roof. Keeping the wood burning furnace going and realizing the meaning of the saying “Keep the home fires burning.” My most wonderful garden. Henry’s Status Theory. Endless discussions. Walking 4 miles around the lake most days. Developing chronic tendonitis and no longer walking around the lake fast enough to keep the weight off. Deer season and the deer Ayanna, Tulani, James and Cabral skinned and cut up. Relatives selling their places. Louis, Henry and my father dying. Moving to Water Way Drive.

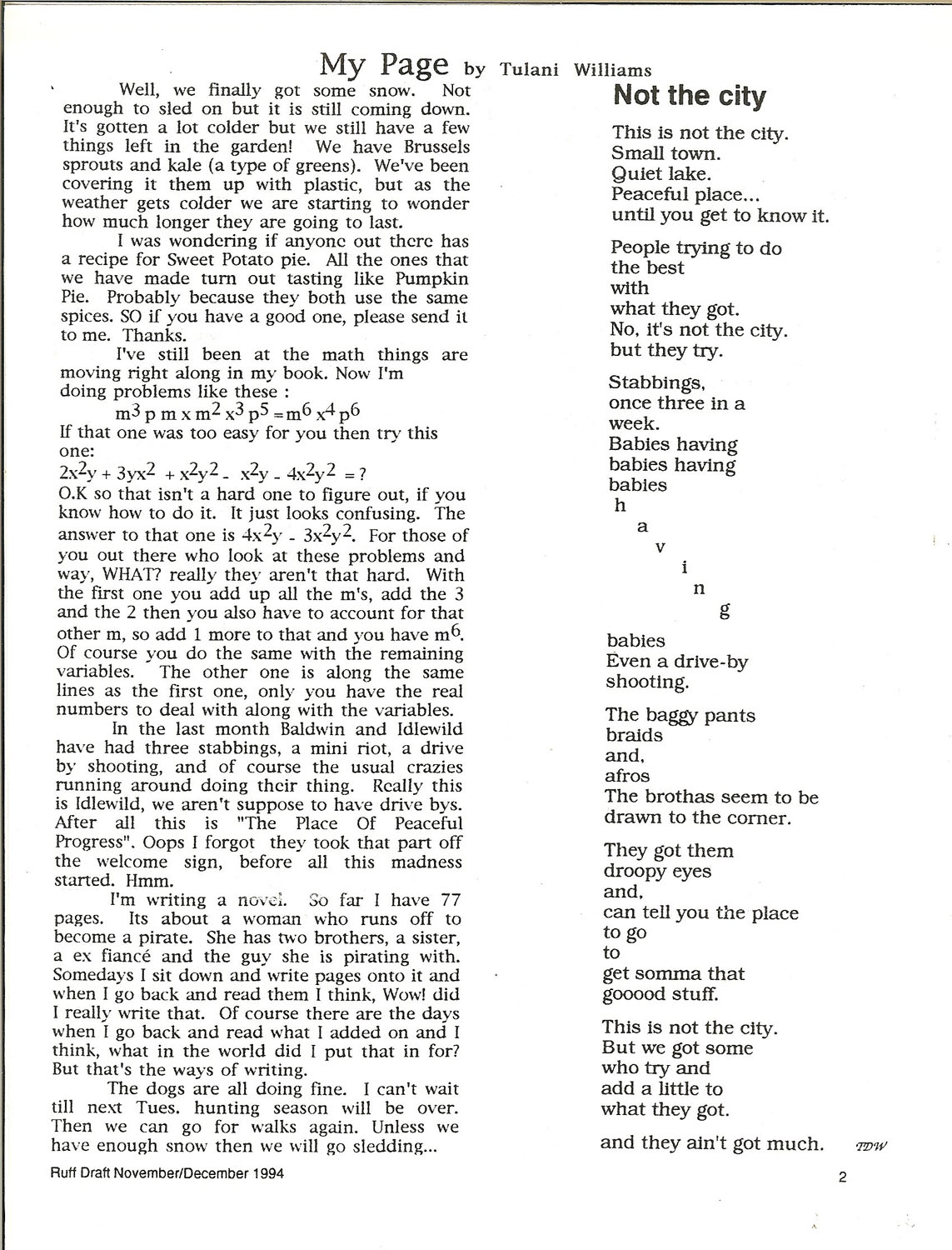

Here is a page from our family newsletter, Ruff Draft, from those years.

Others posts about life at S. Payne Drive