This post continues a series using the Alphabet to go through streets that were significant in my life as part of the “Family History Through the Alphabet” challenge.

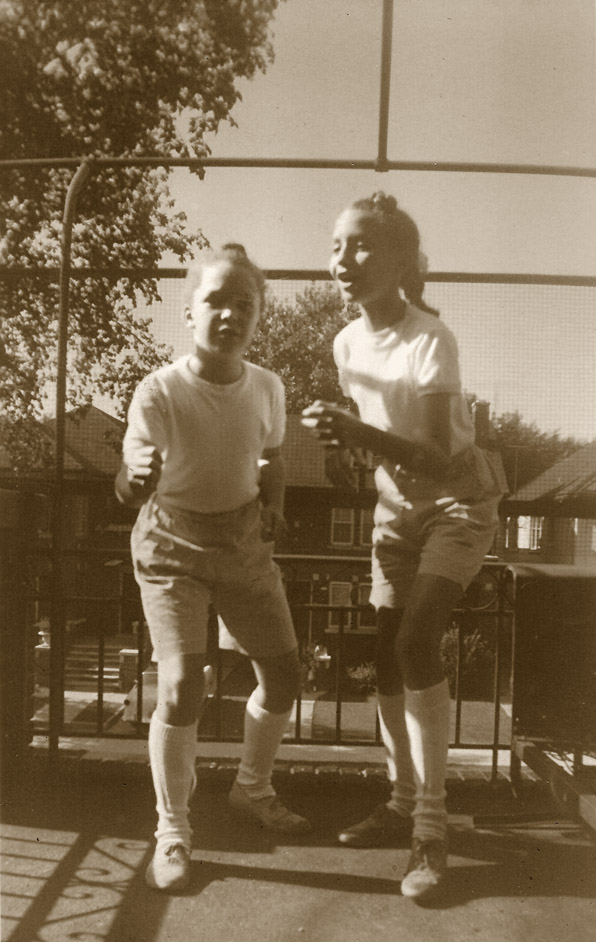

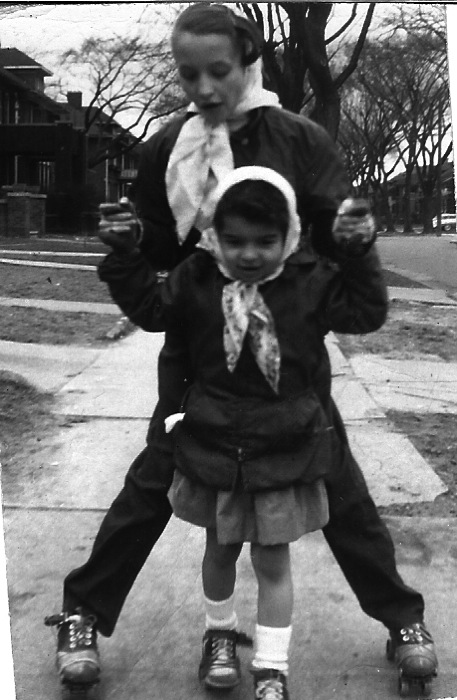

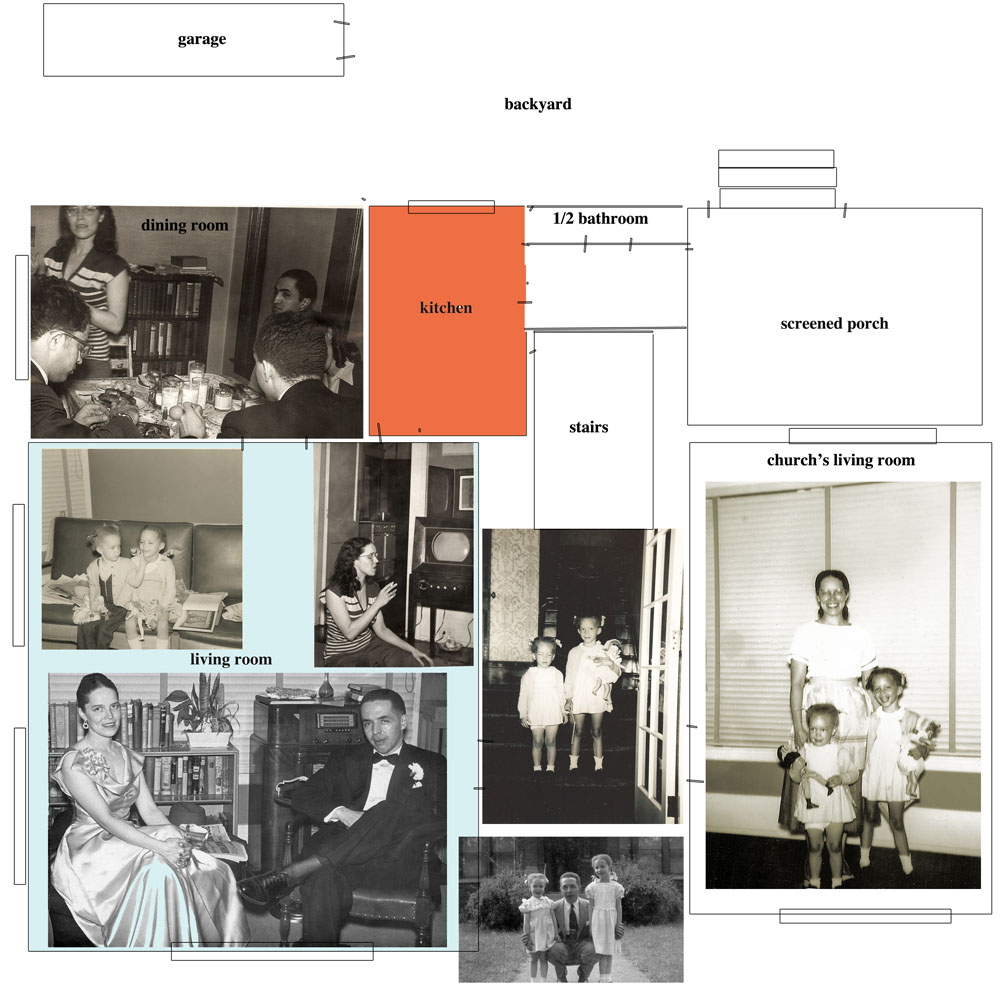

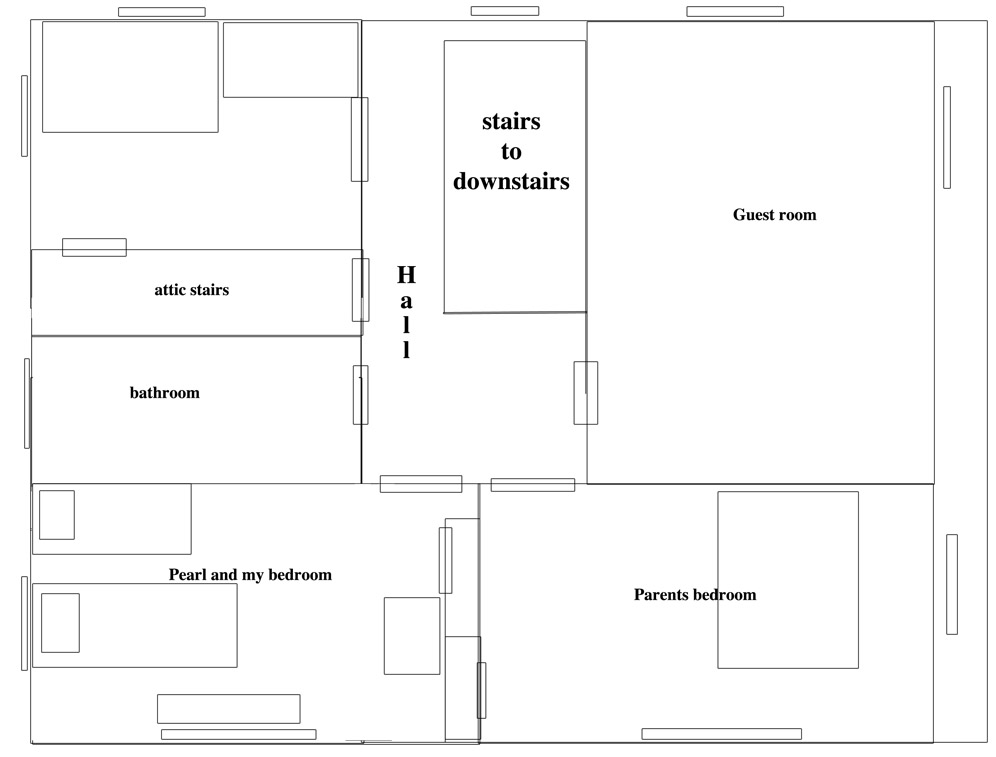

We moved to 2705 Calvert from 2254 Chicago Blvd when my parents separated in the fall of 1954. I was 8 and my sister was 6. We lived upstairs in a two family flat. “Beans Bowles”, the musician and his family lived downstairs. Our elementary school, Roosevelt, was two blocks away. My mother, Mrs. Cleage to her students, taught Social Studies at the same school. I remember playing outside a lot – on the block, at the playground and in a vacant lot at Lawton and Boston. There were many children on the block of all ages. We played “7-Up” where you throw a ball against the side of the house, clap your hands and count higher and higher until you miss. We drew hopscotch grids on the sidewalk and played that. We roller skated and rode our bikes.

There was a drugstore and a small grocery store next to it on the corner of Linwood and Calvert. My mother bought rotten meat at the grocery once and the man didn’t want to take it back until she threatened to call the health department. We still bought penny candy there – wine candy, lick-a-maid. My mother never shopped there again. That whole business section of the block is empty now.

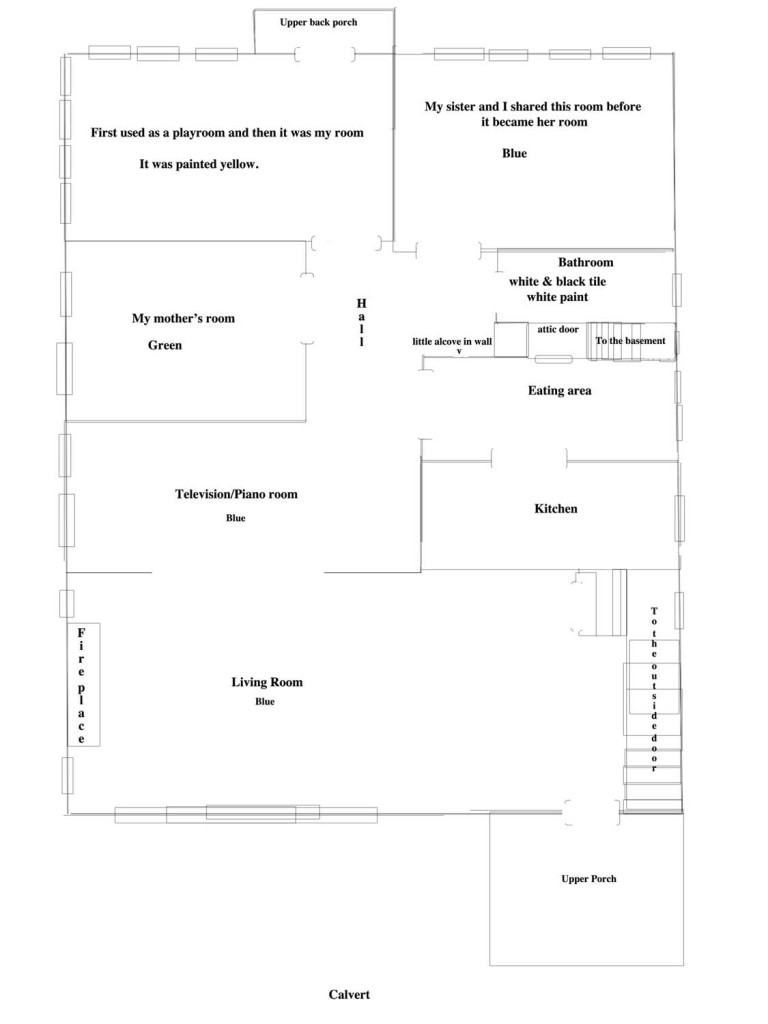

I have no photographs taken inside the house but I do remember the layout.

One day my sister and I were sitting on the upper back porch playing paper dolls when one of the younger boys from downstairs climbed up from his back porch to ours. That’s what his plan was anyway. As his hand came over the edge I started beating it with my fist. He went back down in a hurry. Thankfully he didn’t fall down and break his neck, but as I said to my sister at the time “You can’t let that get started.”

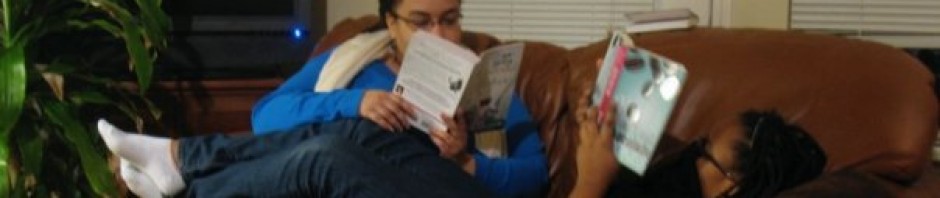

I remember my cousin Dee Dee babysitting us. We were laying on the floor trying to make something rise with the power of our minds, when she hollered “GAS!” and ran into the kitchen. Gas was indeed escaping from an unlit burner on the stove. She turned it off and we opened up all the windows and lived. I remember having the measles during Spring break and laying in the darkened room. My sister and I still shared a room so we had company in our misery.

In my mind’s eye I can see a puzzle I did of sheep grazing on a hillside, and the view of the houses across the alley out of our bedroom window. I remember a disaster of a birthday party where nobody came, and cleaning the bathroom on Saturdays. I remember going to sleep while my mother played Richard Crooks, Paul Robeson and Harry Belafonte. I remember playing “water wars” in the bathtub with our poor, soggy dollhouse dolls floating around in plastic bag covered Kleenix boxes.

There were ballet lessons at Toni’s School of Dance, piano lessons from Mr. Manderville and violin at school that I never practiced. I remember pet turtles, always with the same names and always dying from soft shell disease, in spite of being dosed with cod liver oil. I read Songberd’s Grove and The Little Princess. While my mother was taking classes towards her master’s at Wayne I read Peyton Place, Mandingo and The Second Sex.

I remember walking home from school under a canopy of elm trees before they lost to Dutch Elm disease. And walking to school through 2 feet of snow after a March storm. I remember walking down Lasalle to our old house on Chicago, where my father still lived, everyday for lunch. There were plays at Central High School we attended with my cousins. And the days at Roosevelt when there were only a few students because everybody else was celebrating the Jewish Holidays I remember graduating from Roosevelt Elementary school and the confusion of Durfee Junior high school.

My mother’s sister and her three daughters lived two blocks down Calvert in a lower flat. Later my Aunt and Uncle – Anna and Winslow, bought the flat next door and my father moved into the downstairs flat while they lived upstairs.

Before my mother’s sister Mary V. Elkins and her family, moved into the flat on Calvert, my father’s sister, Gladys Evans and her family, lived there. Jan was a baby. They had just moved back to Detroit after their father got out of the service and stayed with us for a minute on Chicago, then moved to Calvert. When they moved from Calvert to Pasadena, the Elkins family moved into the flat. The Wallaces, who were members of my father’s church, lived upstairs and probably passed on the information that the flat was available.

Related Posts

Some posts about living on Chicago Blvd. I Once Was a Brownie, Dinner Time (this one also mentions meals on Calvert) and We Never Had Outdoor Lights.