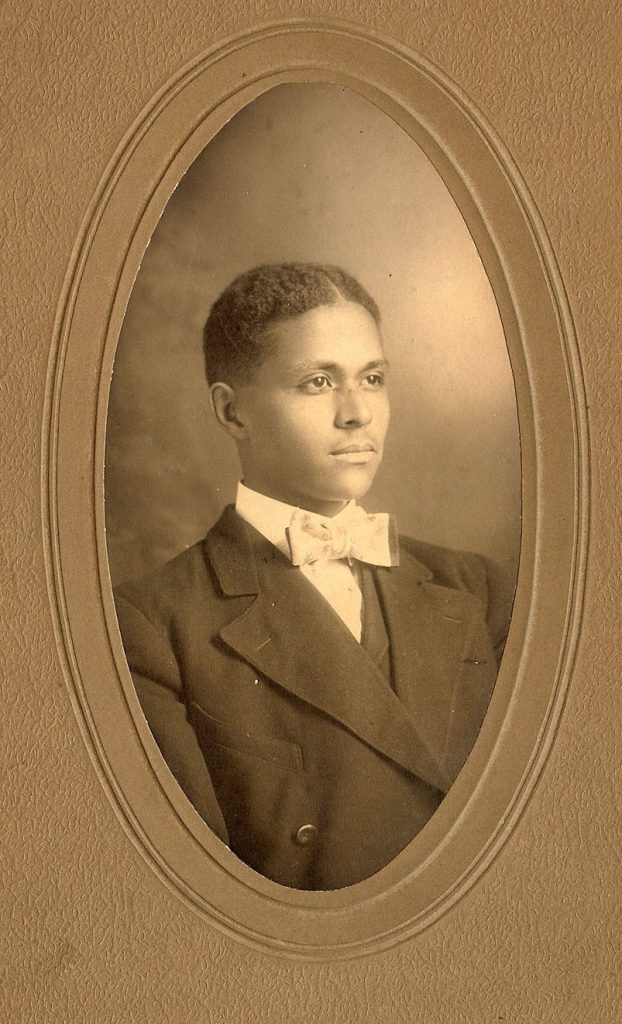

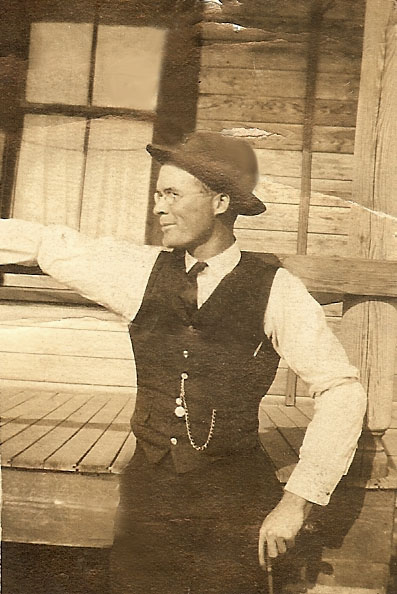

We called my maternal grandfather, Mershell C. Graham, “Poppy”. My grandmother, Nanny, and his friends called him “Shell”. His co-workers called him “Bill”.

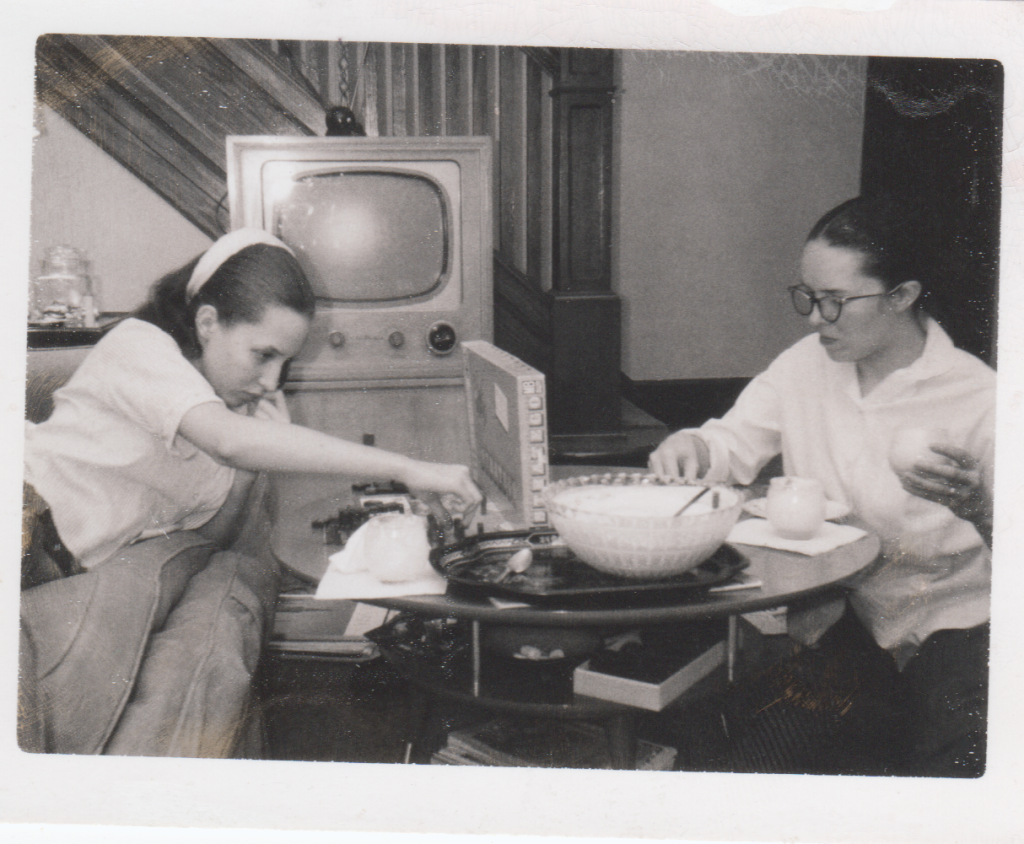

In the summer of 1953 my mother, sister and I stayed with my grandparents while my father was organizing a new church and parsonage across town. He stayed with his parents. We didn’t have a car and each morning we walked our mother around the corner to the bus stop where she caught the bus to Wayne State University. She was taking classes to get her teaching certification.

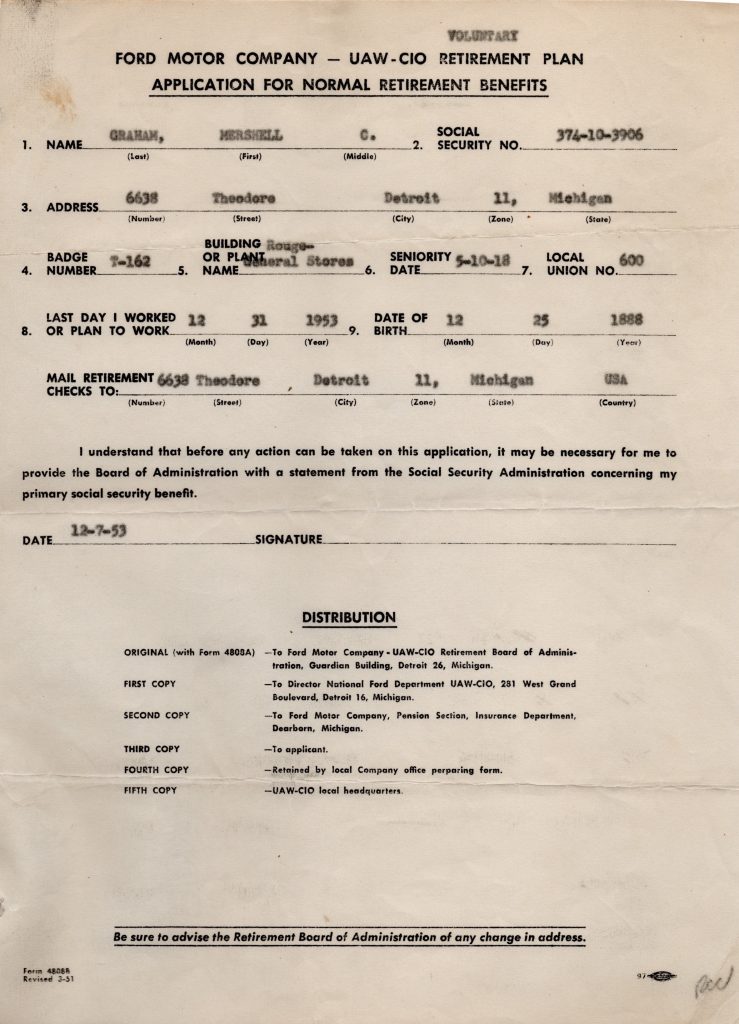

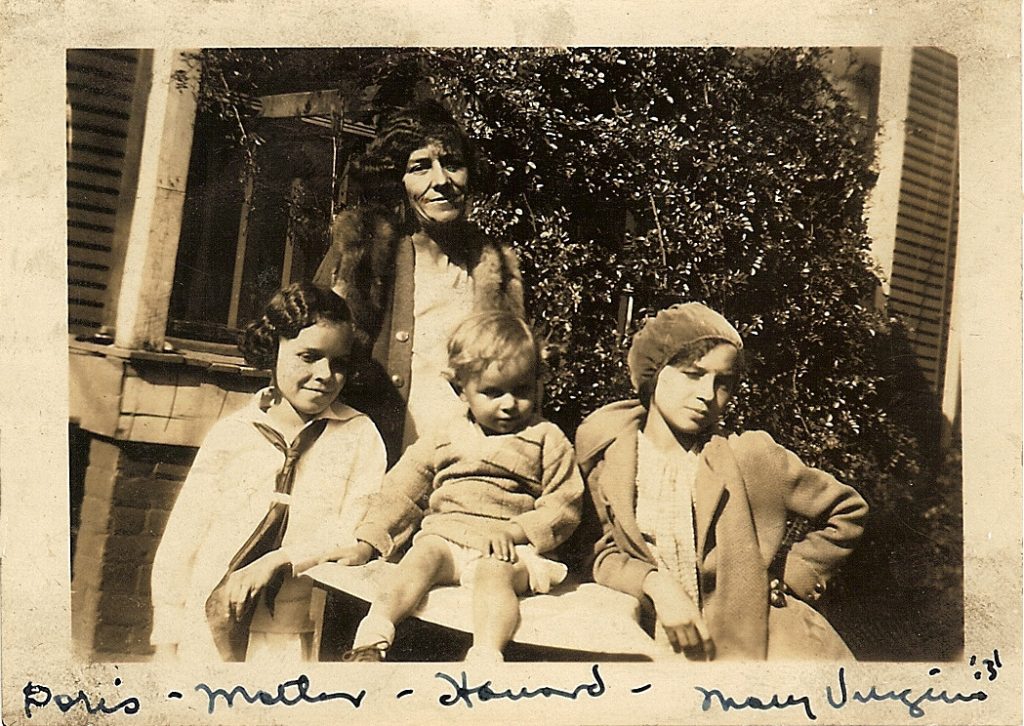

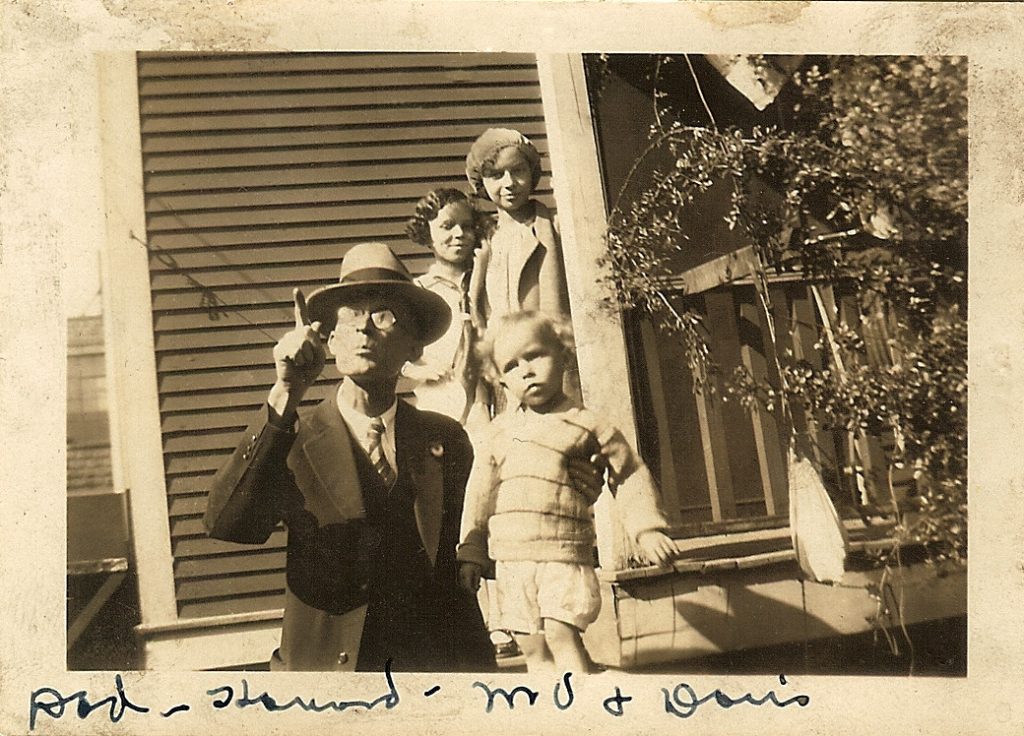

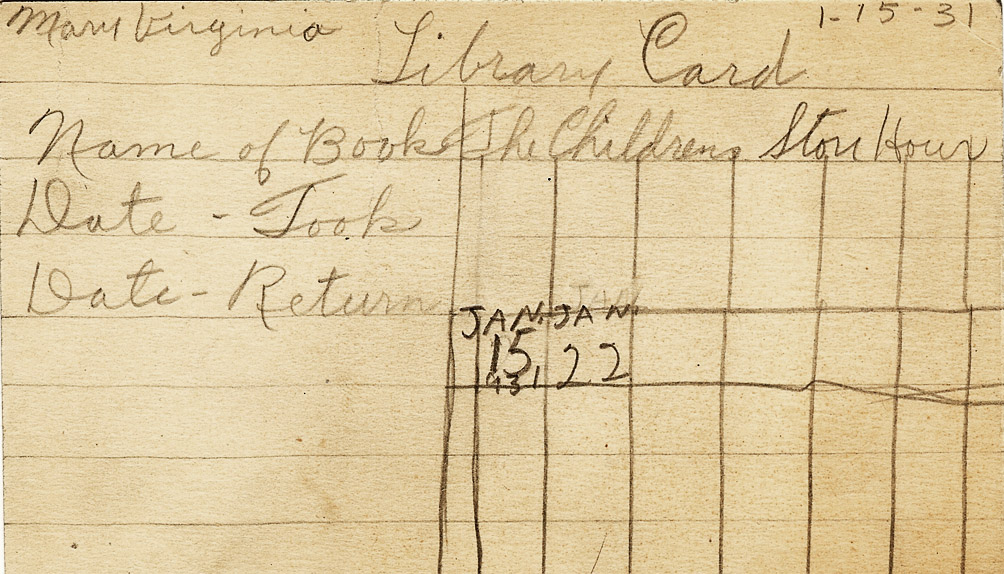

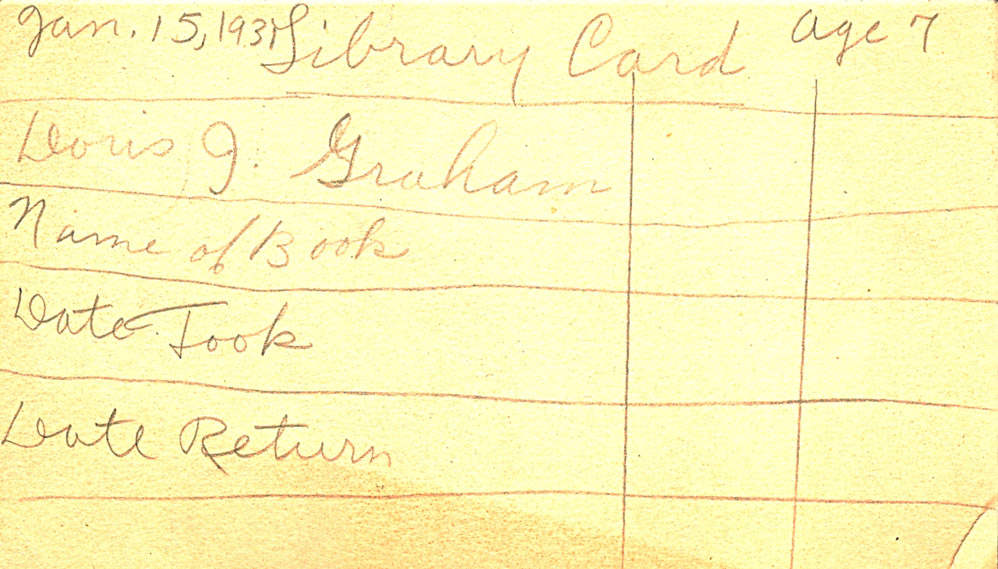

I was almost seven and my sister Pearl was four. I remember spending most of the summer playing in the backyard. My grandmother would be doing what she did in the house, my great aunt Abbie mostly stayed up in her room looking out of the window. After 35 years, my grandfather was working his last months at Ford Motor Company. He retired on December 31.

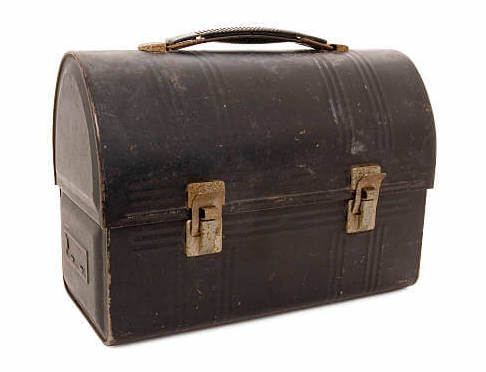

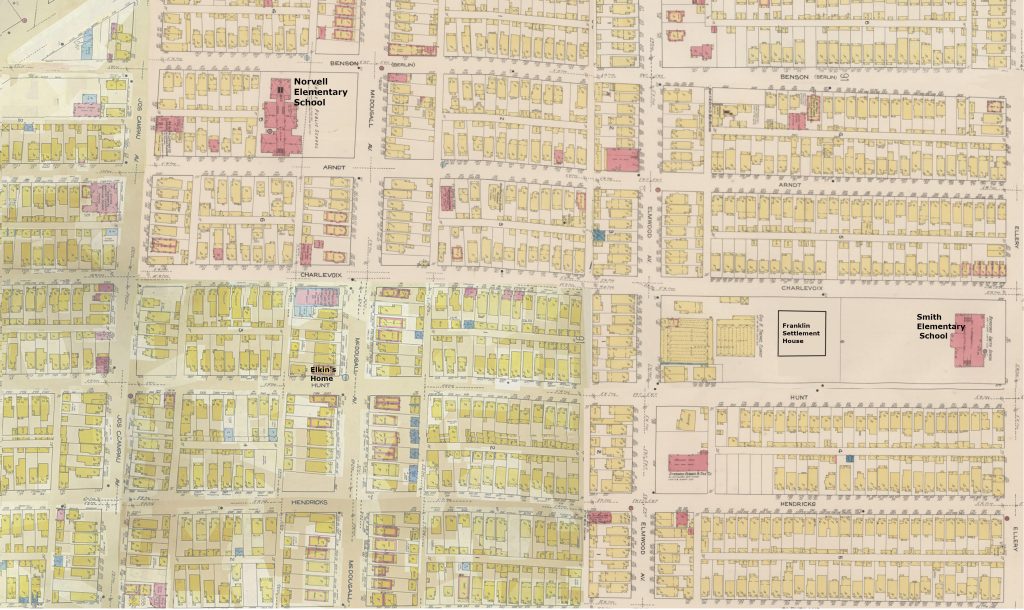

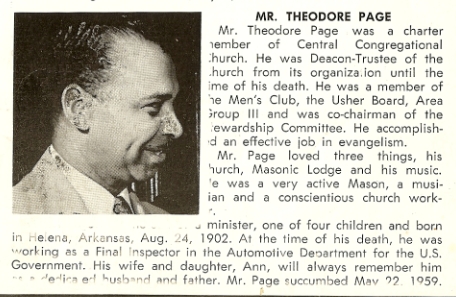

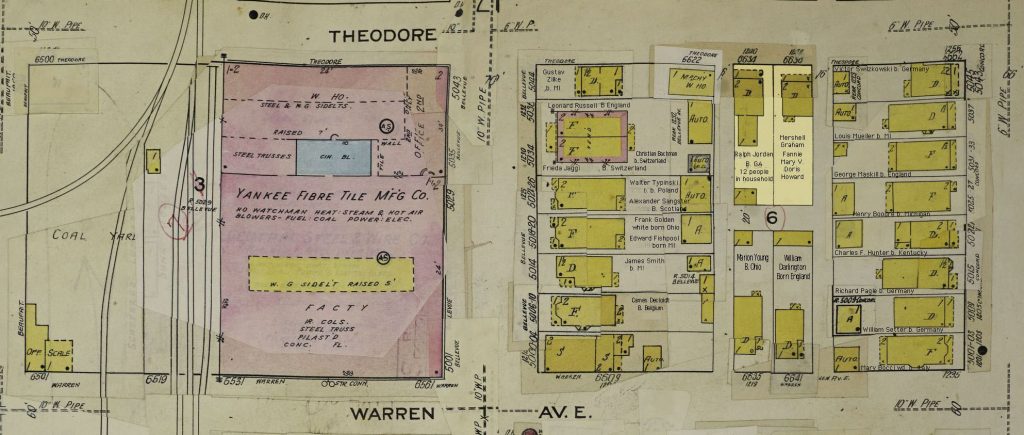

My grandparent’s house and yard was surrounded by an alley on two sides. On the third side was the Jordan’s house next door and on the other side of them was the third arm of the alley. You can see on the map below that the long arms of the alley went through from Theodore to Warren Ave, which is where the bus stop was. My grandfather did have a car, but he didn’t use it to go to work. He caught a streetcar and it took him right to the River Rouge Plant. He had built a little ramp against the back fence against the wooden fence. We could see him coming home through the alley carrying his lunch box.

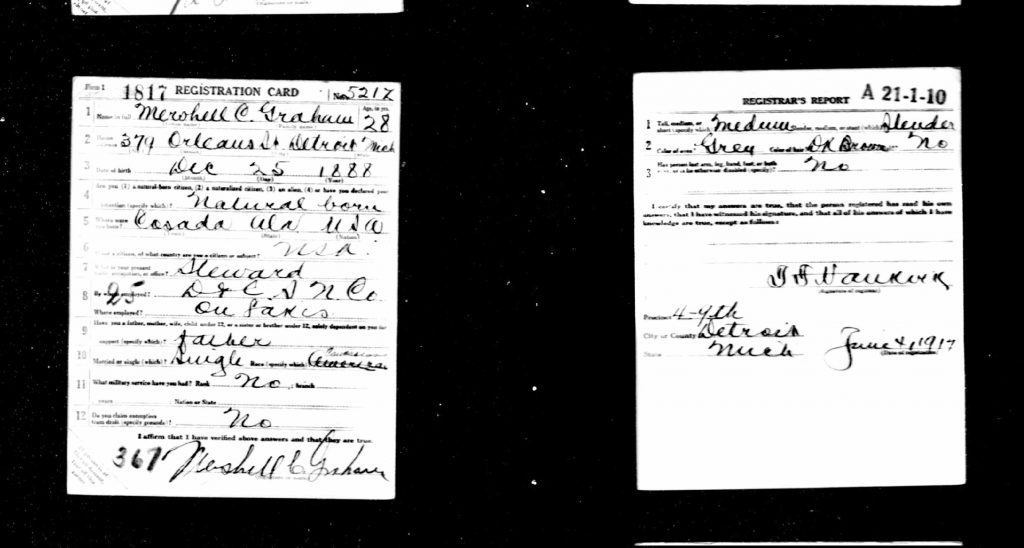

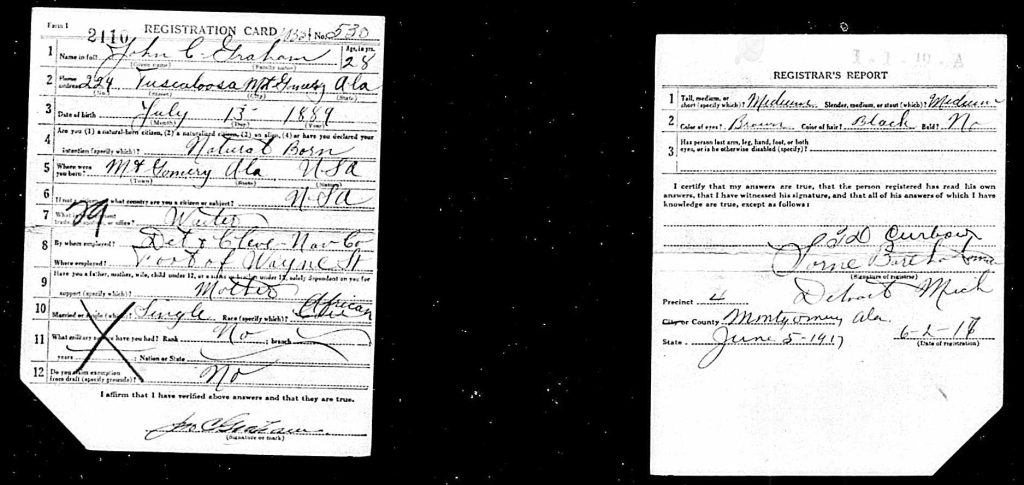

My grandfather began work at Ford’s Highland Park Plant on May 10, 1918, as a machinist. He was 30 years old and single. During that time Ford’s was paying five dollars a day, to qualifying workers, for a forty hour week. There were no benefits.

He returned to Montgomery and married my grandmother, Fannie Mae Turner, in 1919, they returned to Detroit the same day. In the 1920 census his occupation was an “auto inspector”. He was transferred from the Highland Park plant to Rouge plant on March 14, 1930 and went to work as an electrical stock clerk, which is the position he held until his retirement in 1953.

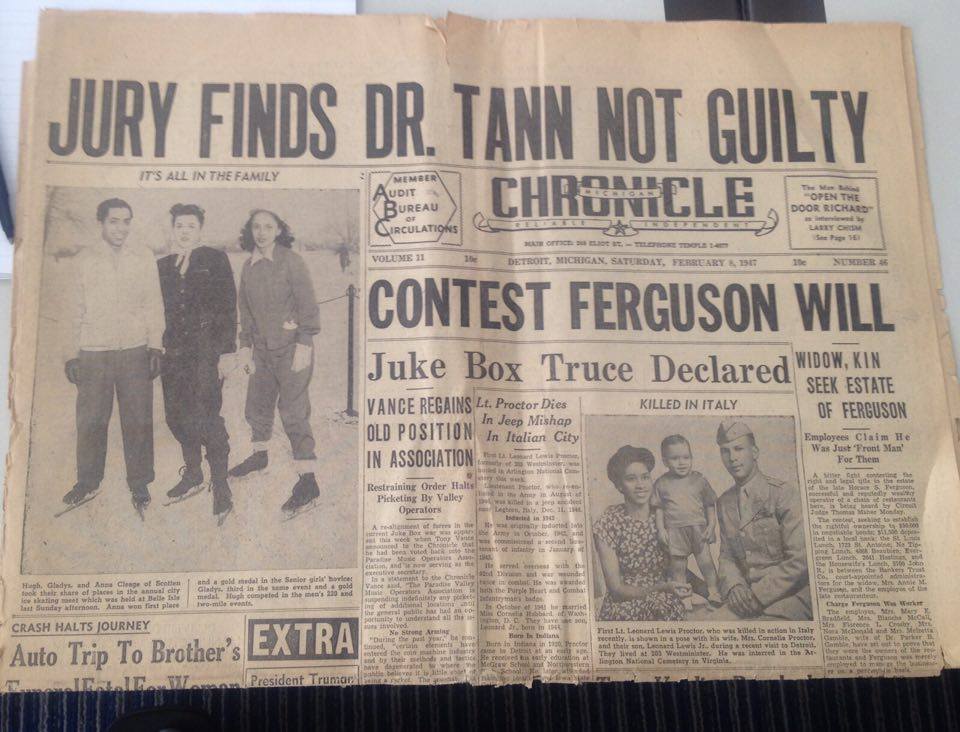

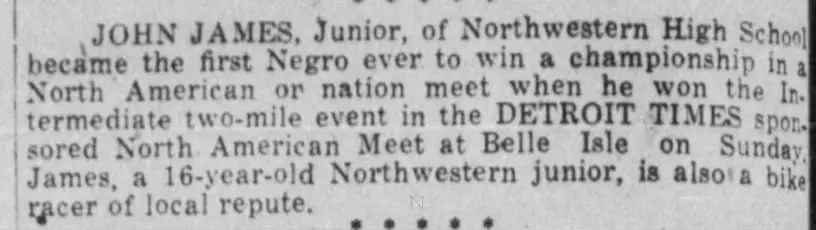

He was at the Rouge Plant during the May 26, 1937: Battle of the Overpass and the unionizing of the auto plants. My mother told me that after he joined the union, he carried a gun to work for protection. Unfortunately, I never heard my grandfather talk about any of this.

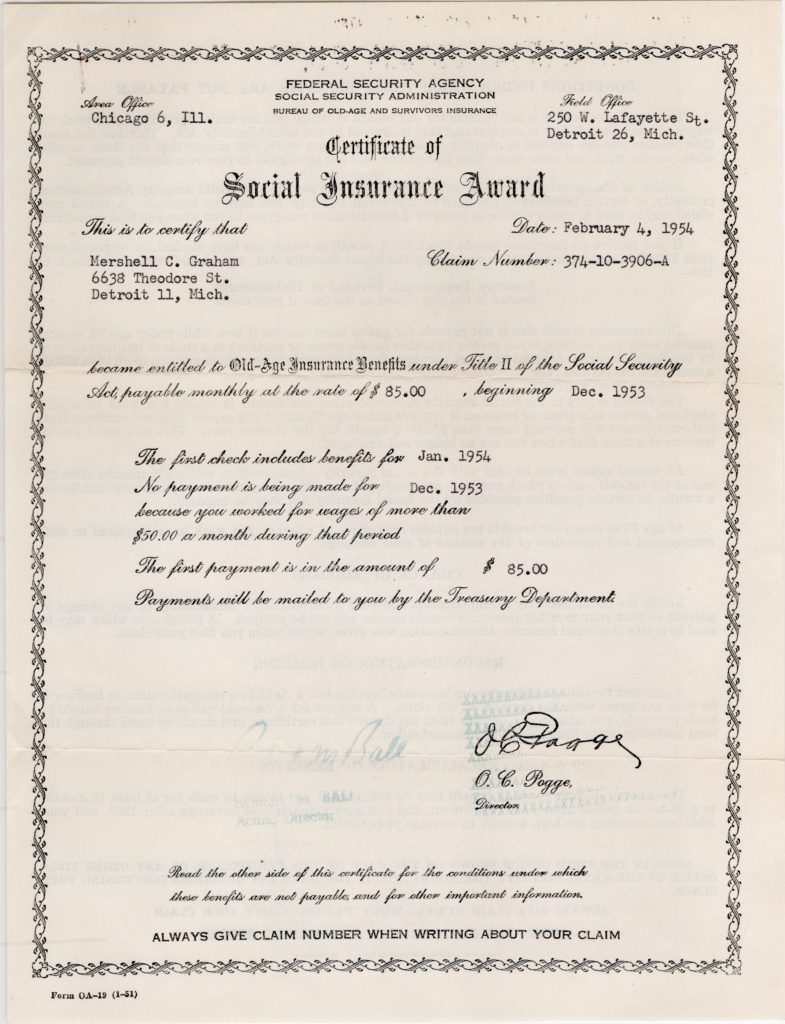

In September 1949 the UAW won a $100-a-month pension, including Social Security benefits , averaging $32.50 a month, for those age 65 with 30 years of employment with Ford’s. My grandfather was among the earliest workers to receive the pension when he retired at age 65 after working there for 35 years. His Social Security benefit was $85 a month. My grandmother received $42.50 as his homemaking wife.

Other posts about my grandfather’s life.

One Way Ticket

From Montgomery to Detroit – Plymouth Congregational Church – 1919

Mershell Graham and Fannie Mae Turner

Graham-Turner Wedding – 1919 Montgomery Alabama

F – FAMILY, MY GRAHAMS in the 1920 Census

The Graham’s in the 1930s

Mershell Graham’s Notebook – 1930s

Lizzie – 1934

1940 Census – The Grahams

The Graham’s in the 1950 Census