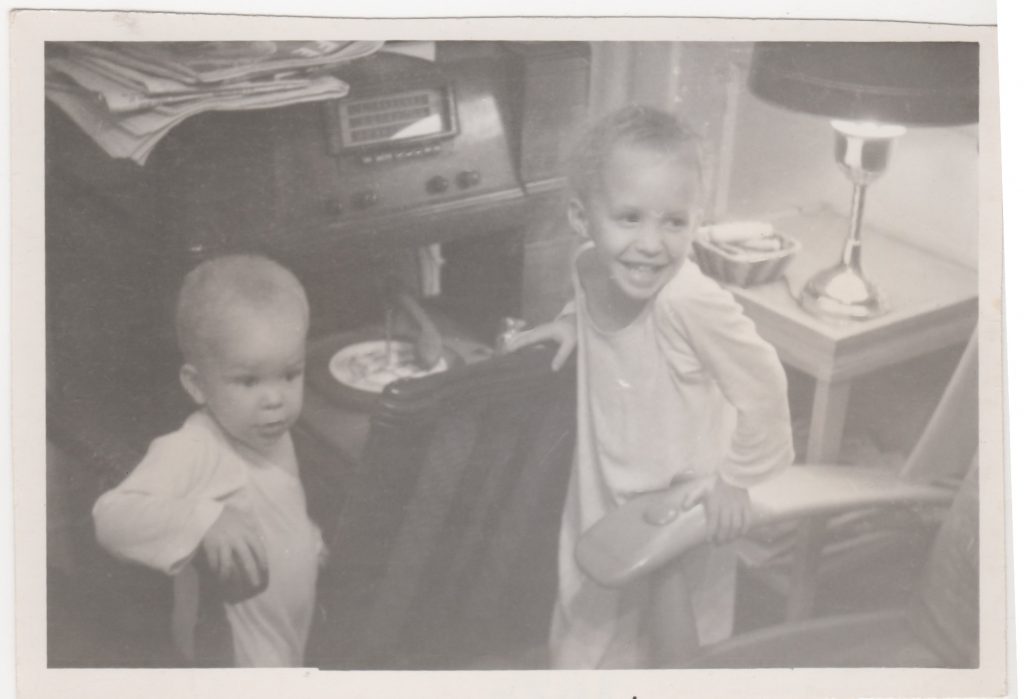

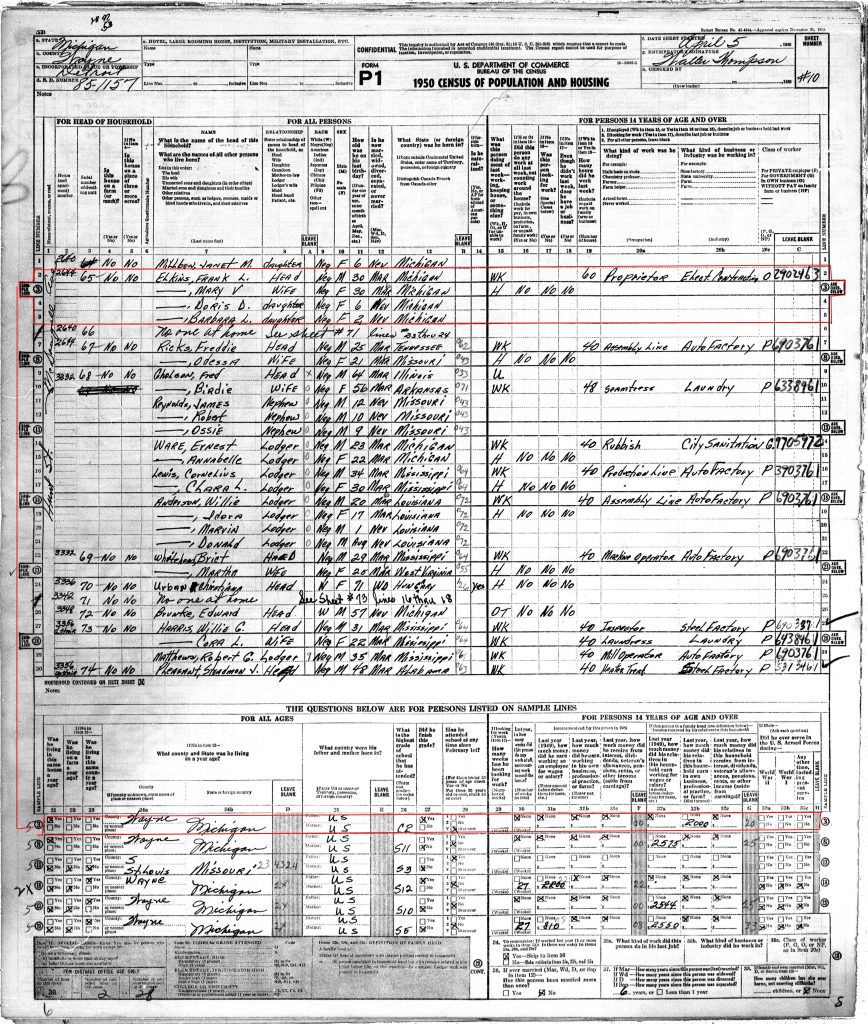

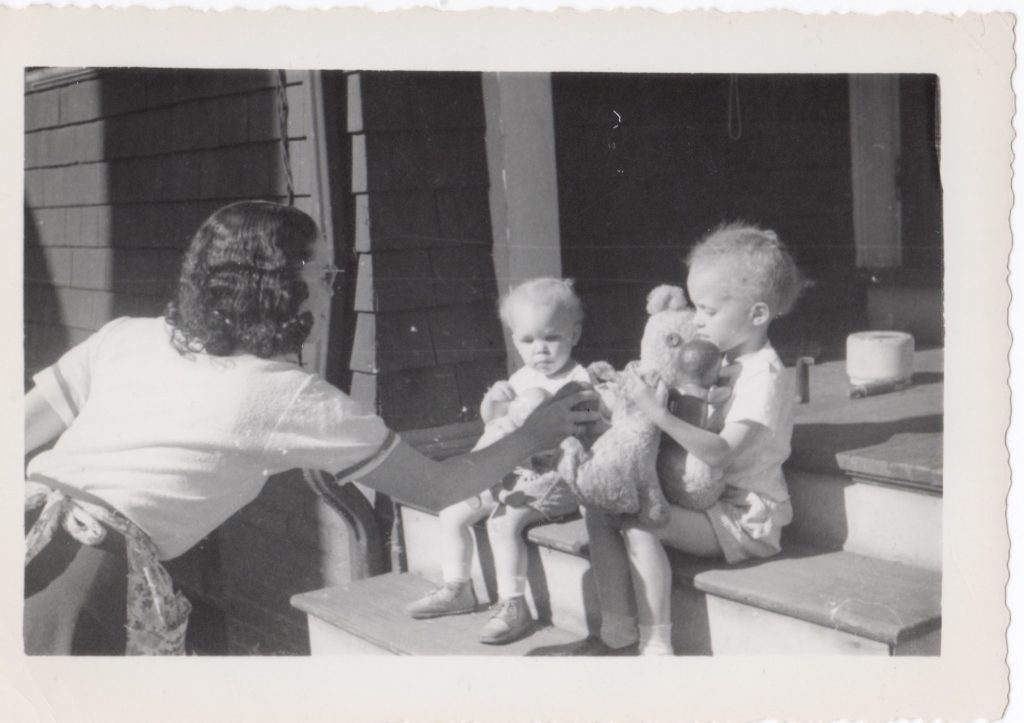

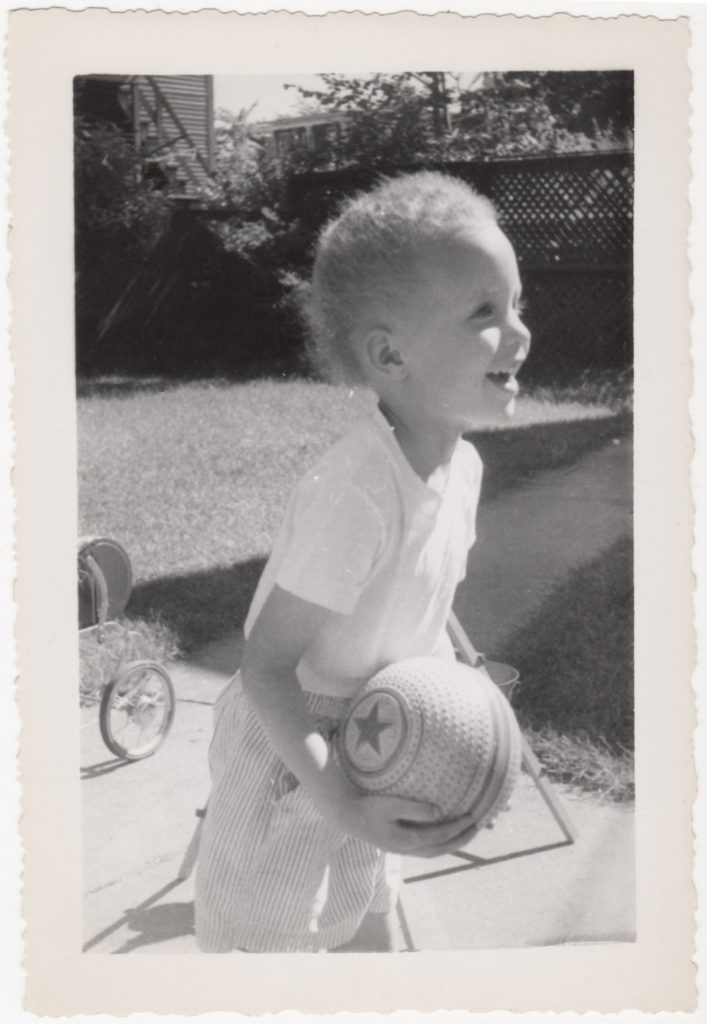

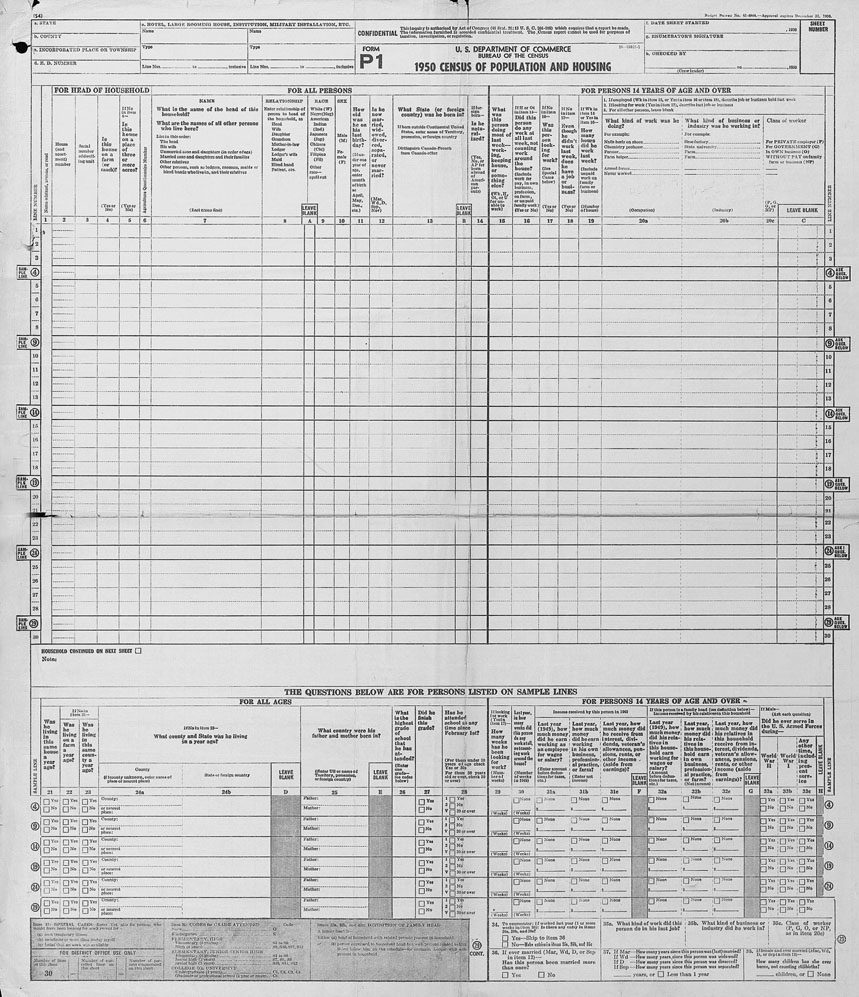

This is my ninth year of blogging the A to Z Challenge. Everyday I will share something about my family’s life during 1950. This was a year that the USA federal census was taken and the first one that I appear in. At the end of each post I will share a book from my childhood collection. Click on all images to enlarge.

I thought I would define “Congregational” for those that don’t know what makes this denomination different from other protestant denominations. Congregationalism emphasizes the right and responsibility of each congregation to determine its own affairs. It eliminates bishops and presbyteries. Each individual church is autonomous.

St. John’s Congregational Church is one of the oldest African American churches in New England. It was founded in 1844. First as the Sanford Street Church. After a few years, it was known as the Free Church. Many members were actively involved in the Underground Railroad and in the movement to abolish slavery.

In 1892, the Sanford Street Church merged with the Quincy Street Mission to form St. John’s Congregational Church, which was named in honor of John Brown, who was a member of the congregation during his three year residency in Springfield. Some years later Brown launched the attack on Harper’s Ferry leading up to the Civil War.

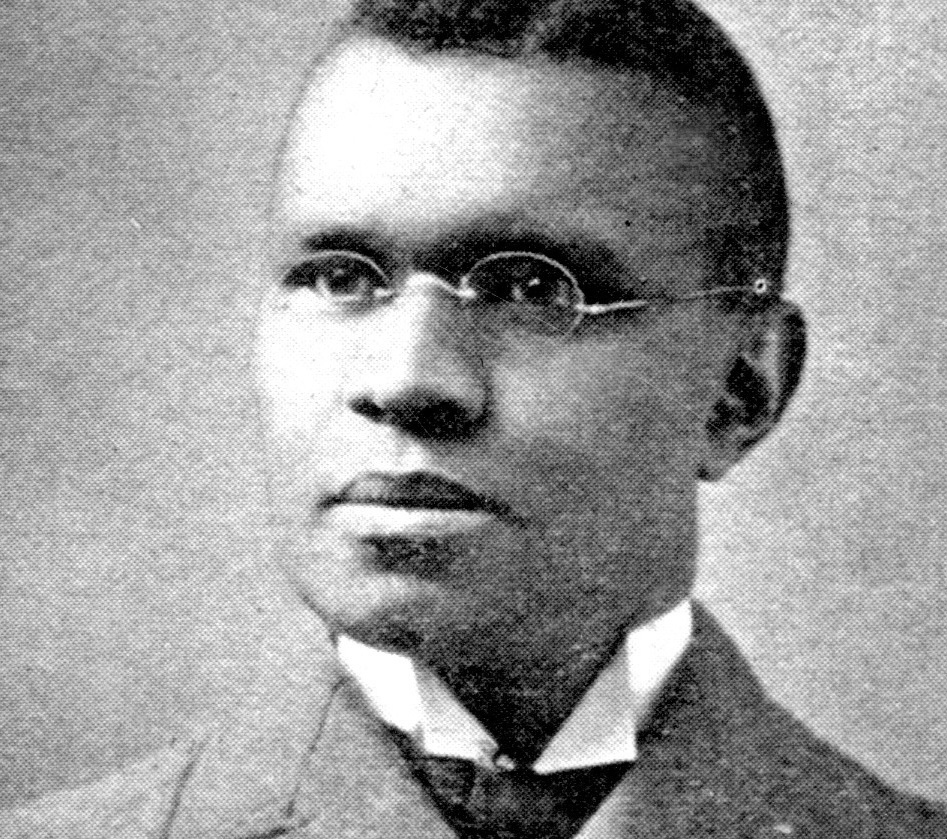

Reverend William DeBerry came to Springfield in 1899, a week after graduating from Oberlin Theological Seminary in Ohio. He was ordained as pastor of St. John’s Church on June 28, 1899.

By 1911 the congregation had raised the funds and built a new church at the corner of Hancock and Union Streets. Some subterfuge was needed as the original white owner would not sell to African Americans. Another white man agreed to purchase the property for the church, with their funds, and deed it over to them after the sale.

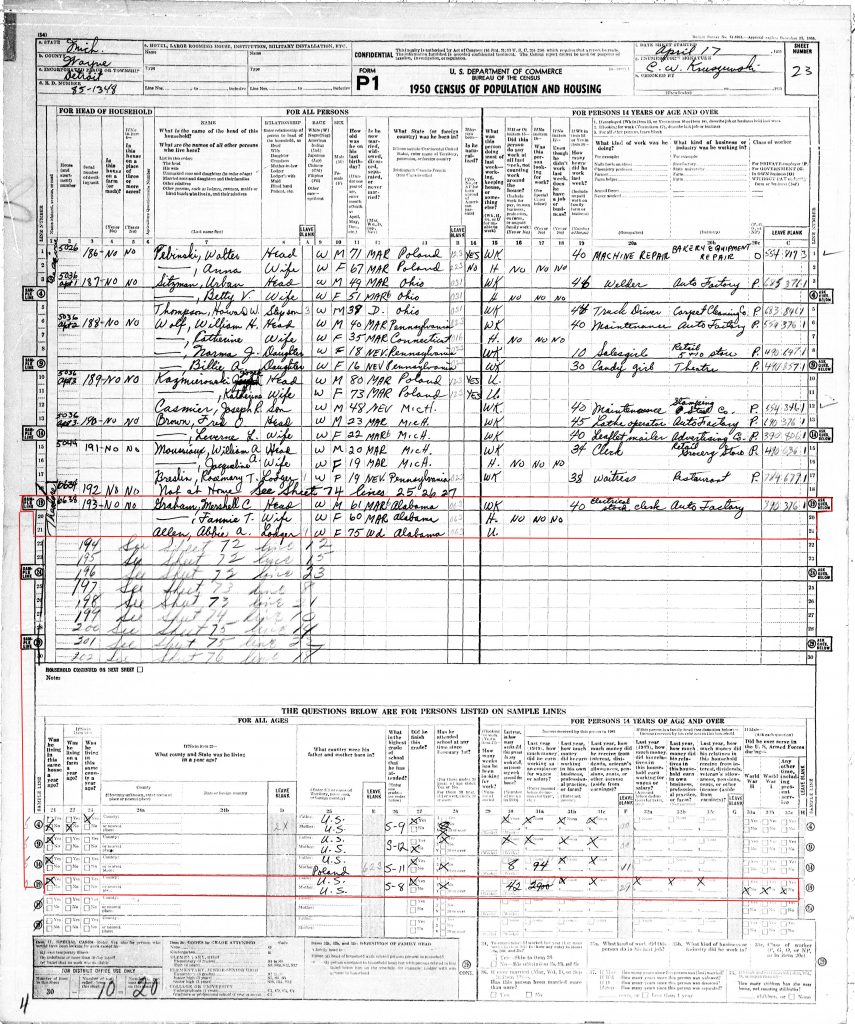

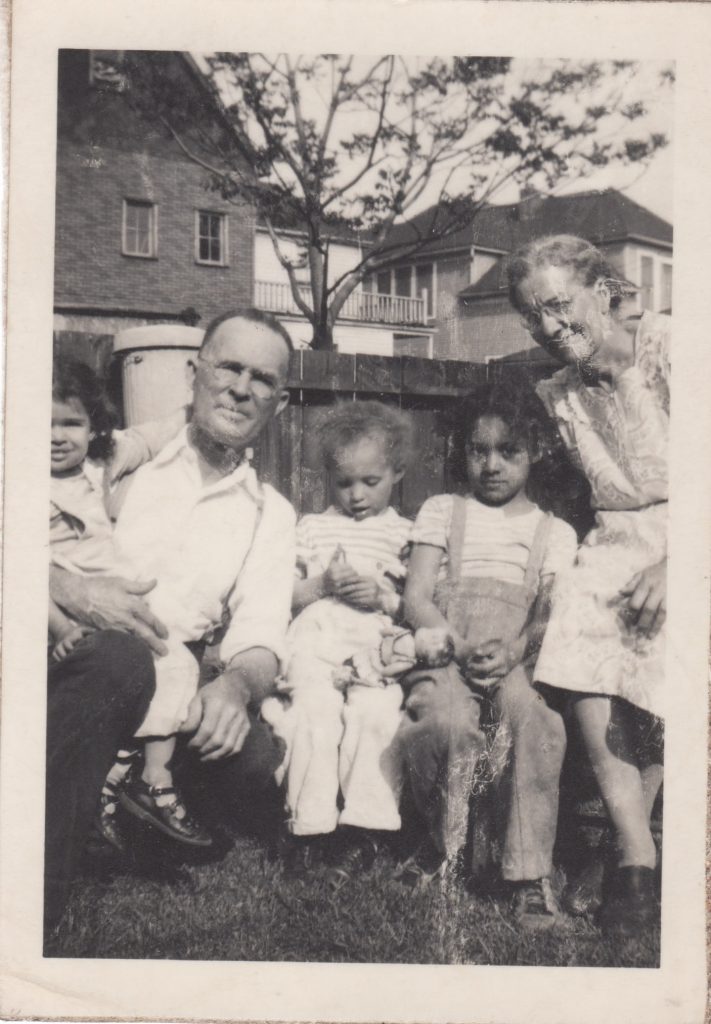

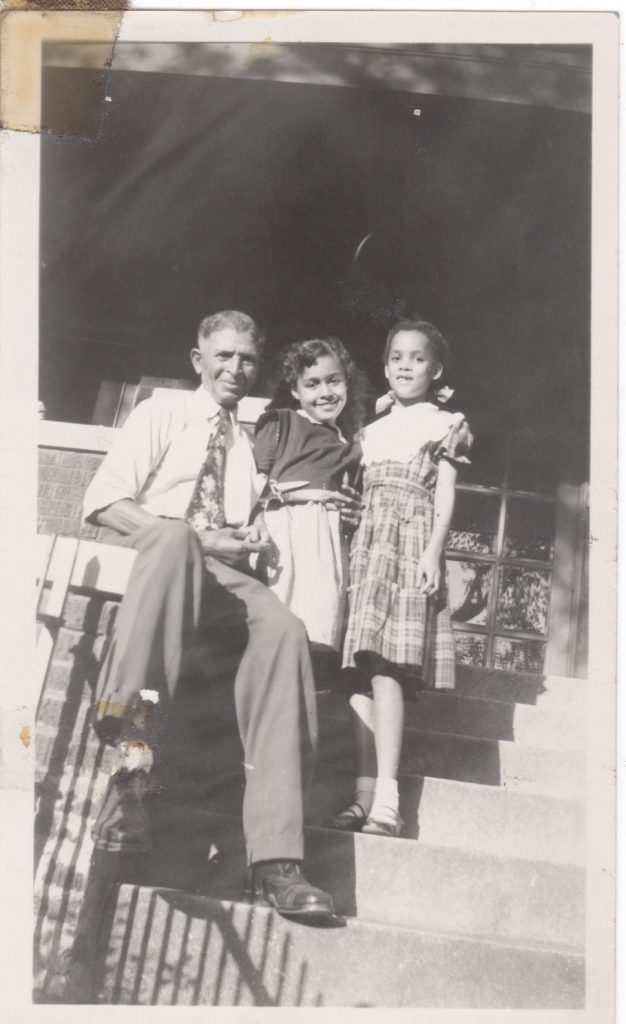

Rev. DeBerry believed in combining traditional religious services with community involvement. In 1913 St. John’s Parish Home next to the church on Union Street was opened to provide safe residential accommodation for working girls and women. It also included quarters for the minister and his family. This is where we lived in 1950. A free employment bureau was opened for men and women, along with a night school which taught domestic science. The Women’s Social Union and the Boys Club were formed to provide social and sports activities for young people.

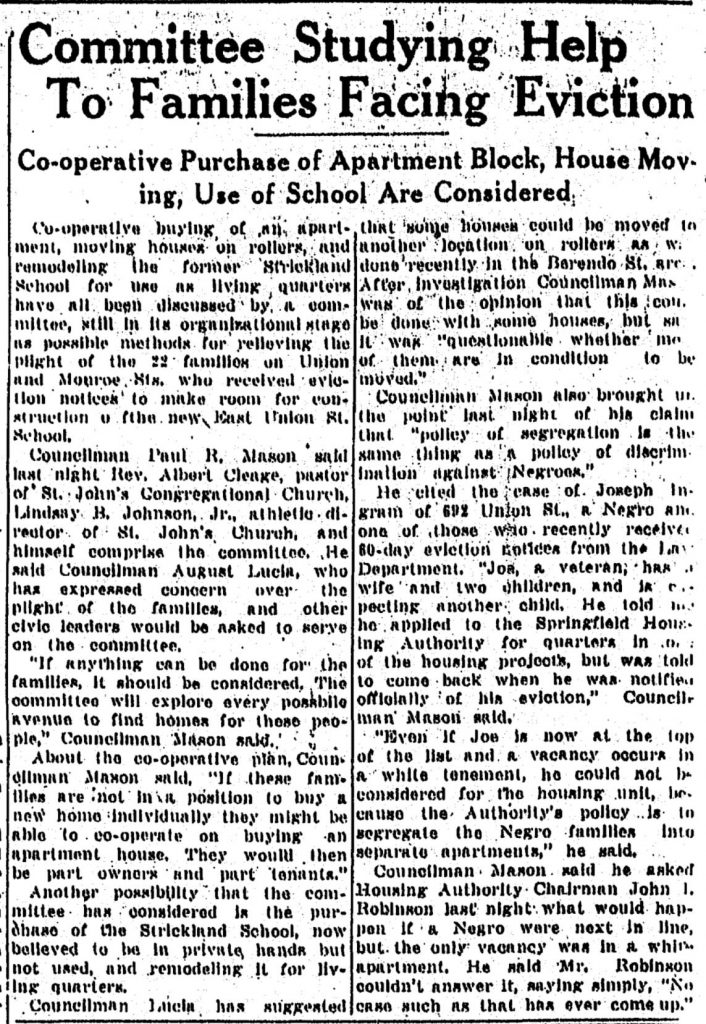

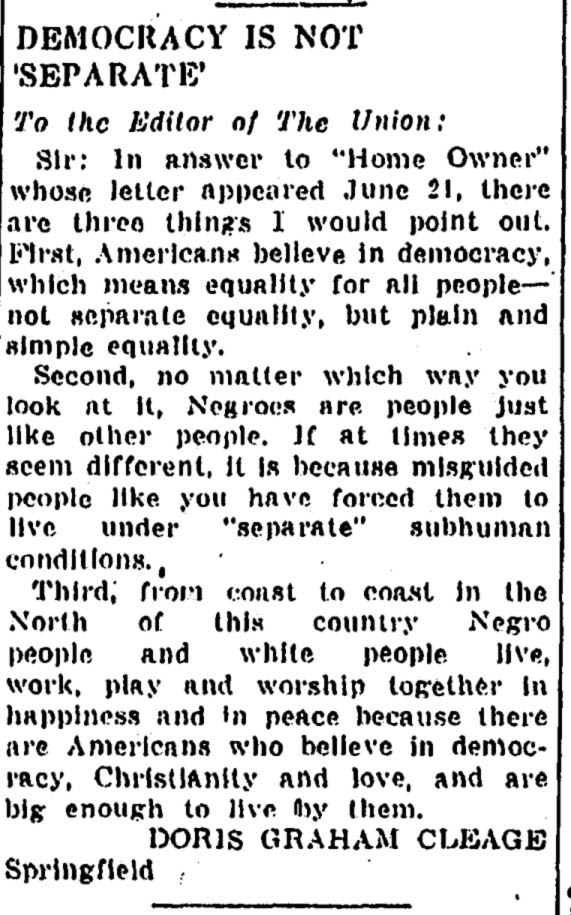

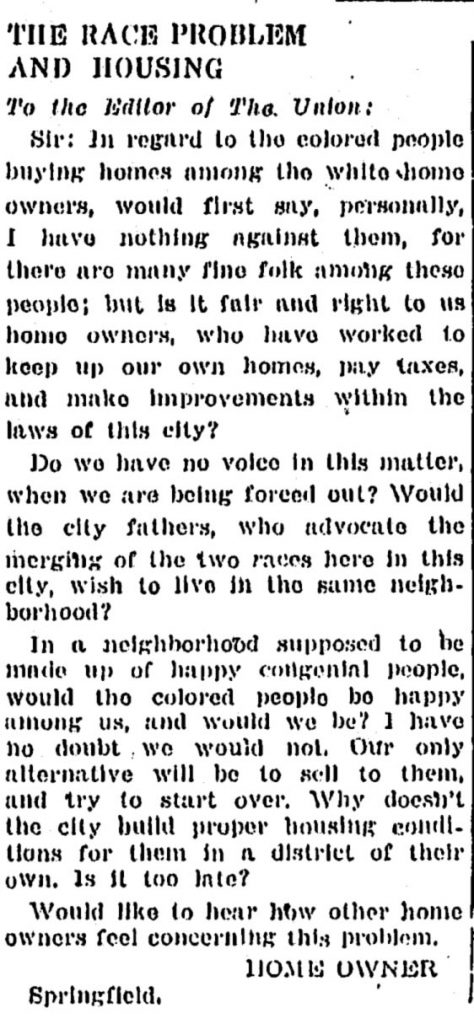

Springfield’s Black population almost doubled between 1917 and 1922 as people from the South moved North. Due to the population increase and housing segregation in Springfield, there was a need for housing. The church purchased buildings on Quincy Street and Orleans Street and rented it to black families.

In 1920 property was purchased for a summer camp in East Brookfield. Camp Atwater continues to this day as the oldest African American camp in the United States.

In 1924, DeBerry separated the social programs division from the church in order to bypass restrictions on the funding of religious programs. He resigned from the pulpit to lead the new organization, reorganized in 1931 as the Dunbar Community League. The church found itself in the midst of the Depression and without much of it’s social programming and income.

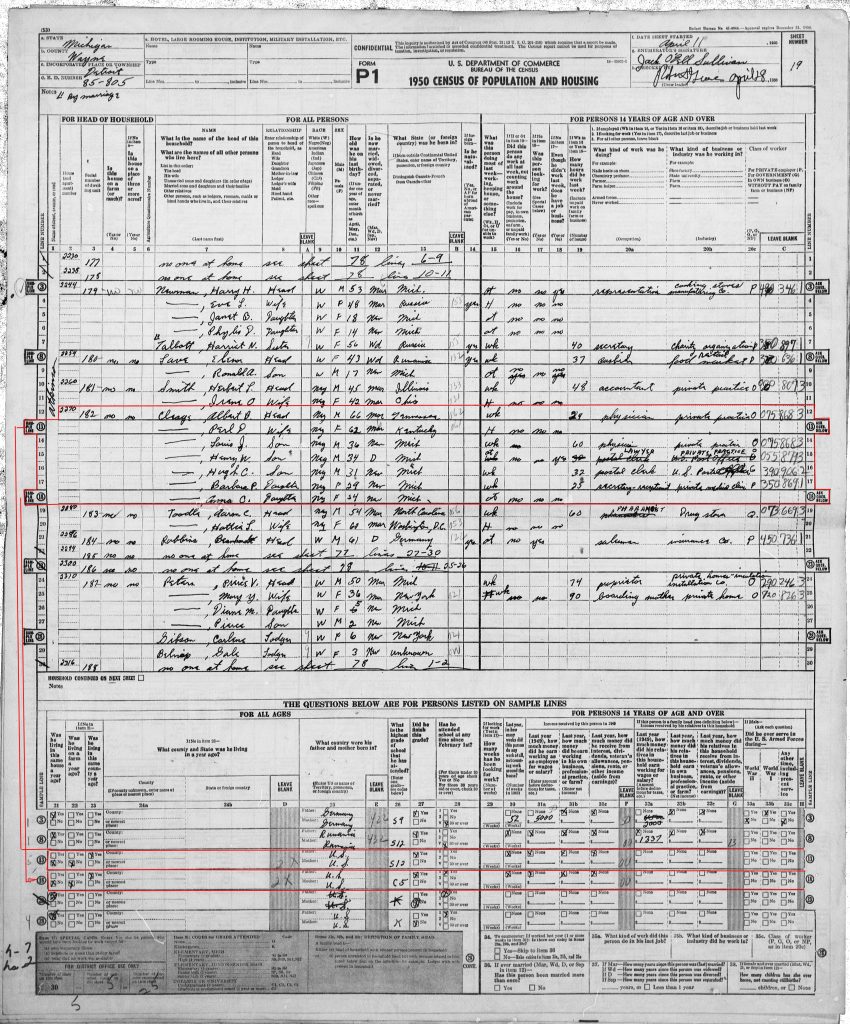

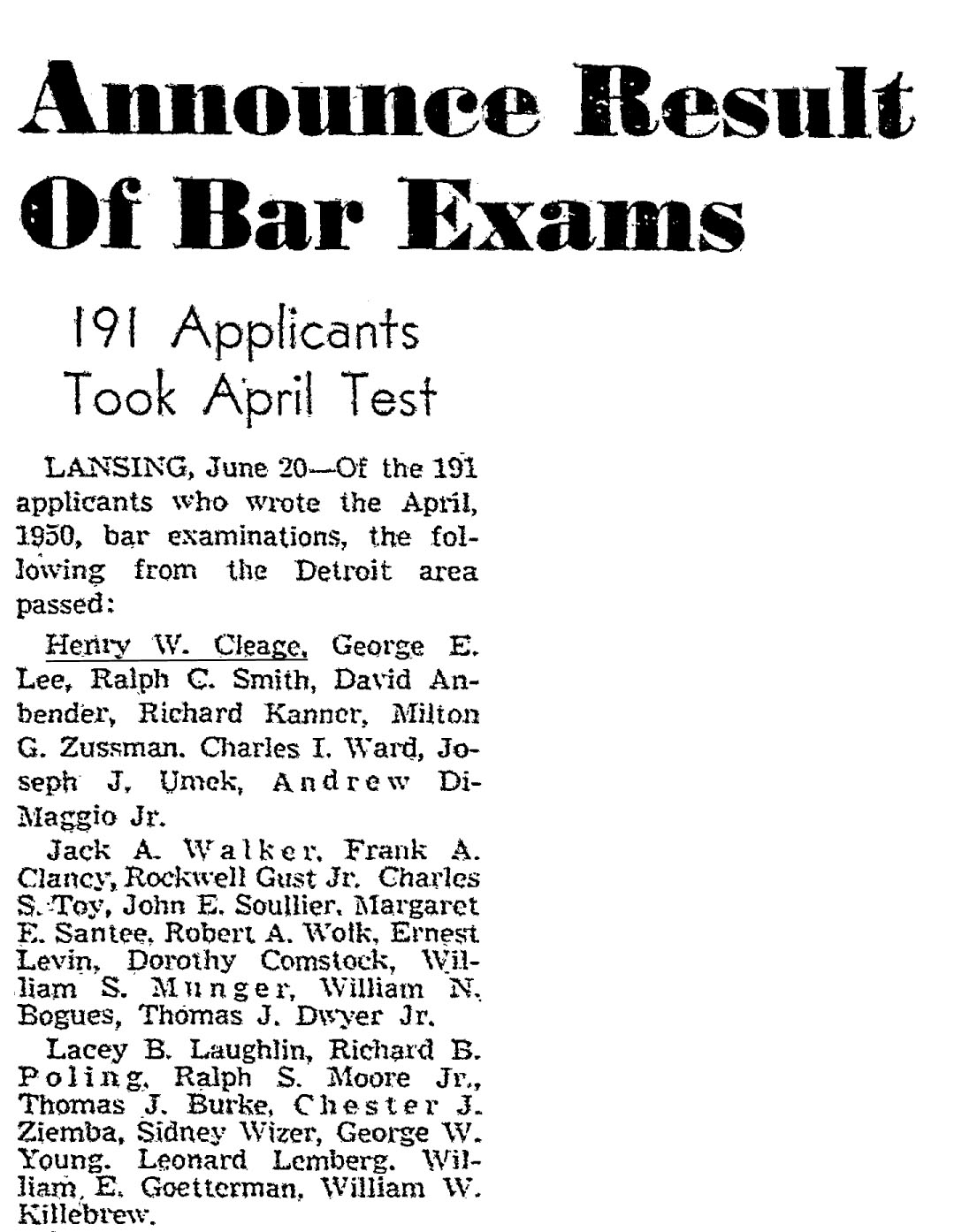

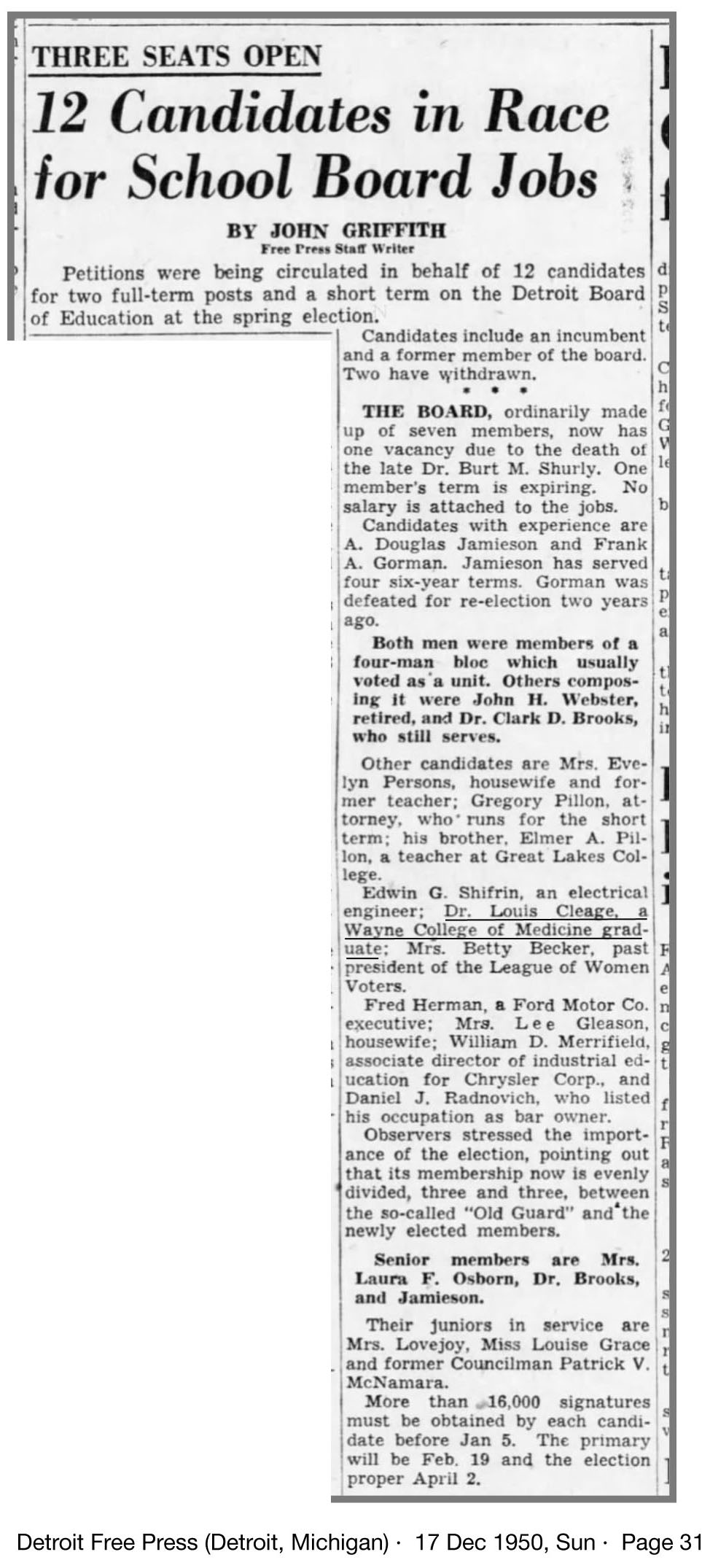

In 1945 my father, Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr became the pastor of St. John’s. He had also graduated from Oberlin Theological School and belived in combining traditional religion and social involvement.

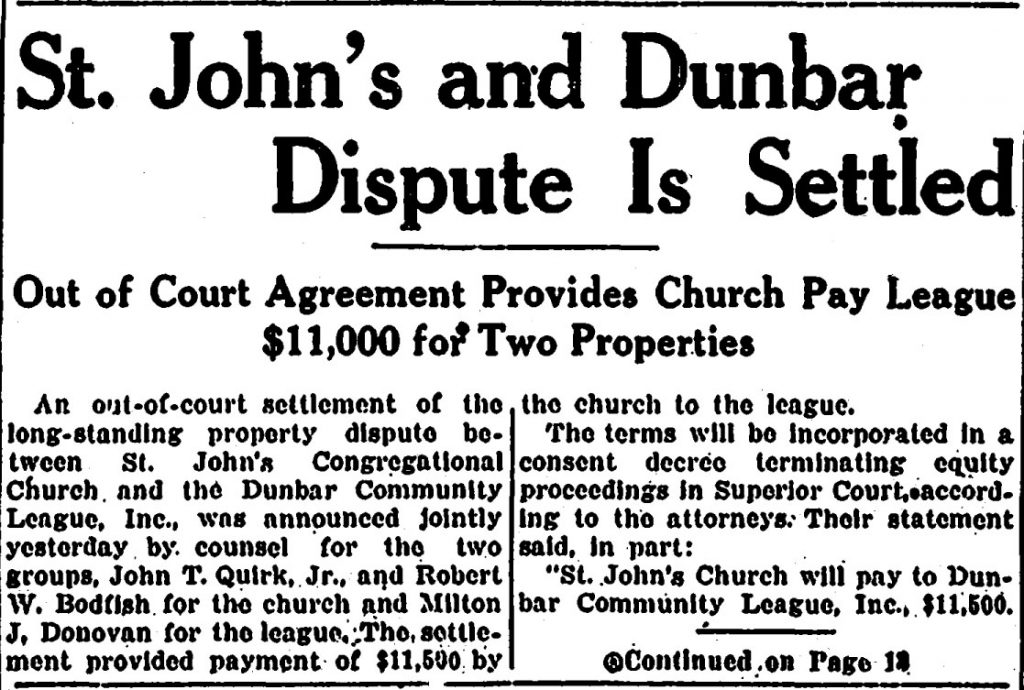

In 1947 the church began a move to have the buildings DeBerry had separated from the church when he left, returned to church ownership. The dispute ended up in court. Some members of the church sided with DeBerry. After DeBerry died in January of 1948 arrangements were made between the Dunbar Community League and St. John’s Congregational Church for the buildings to be returned.

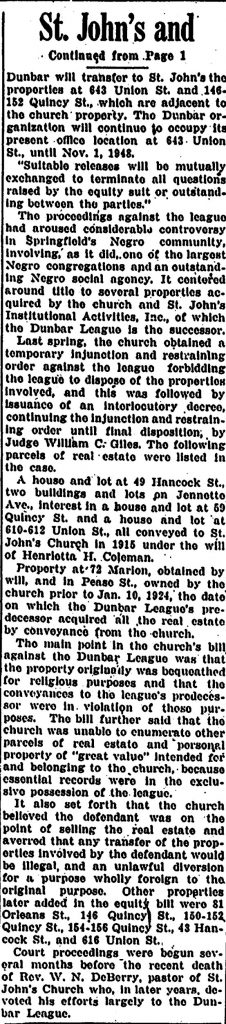

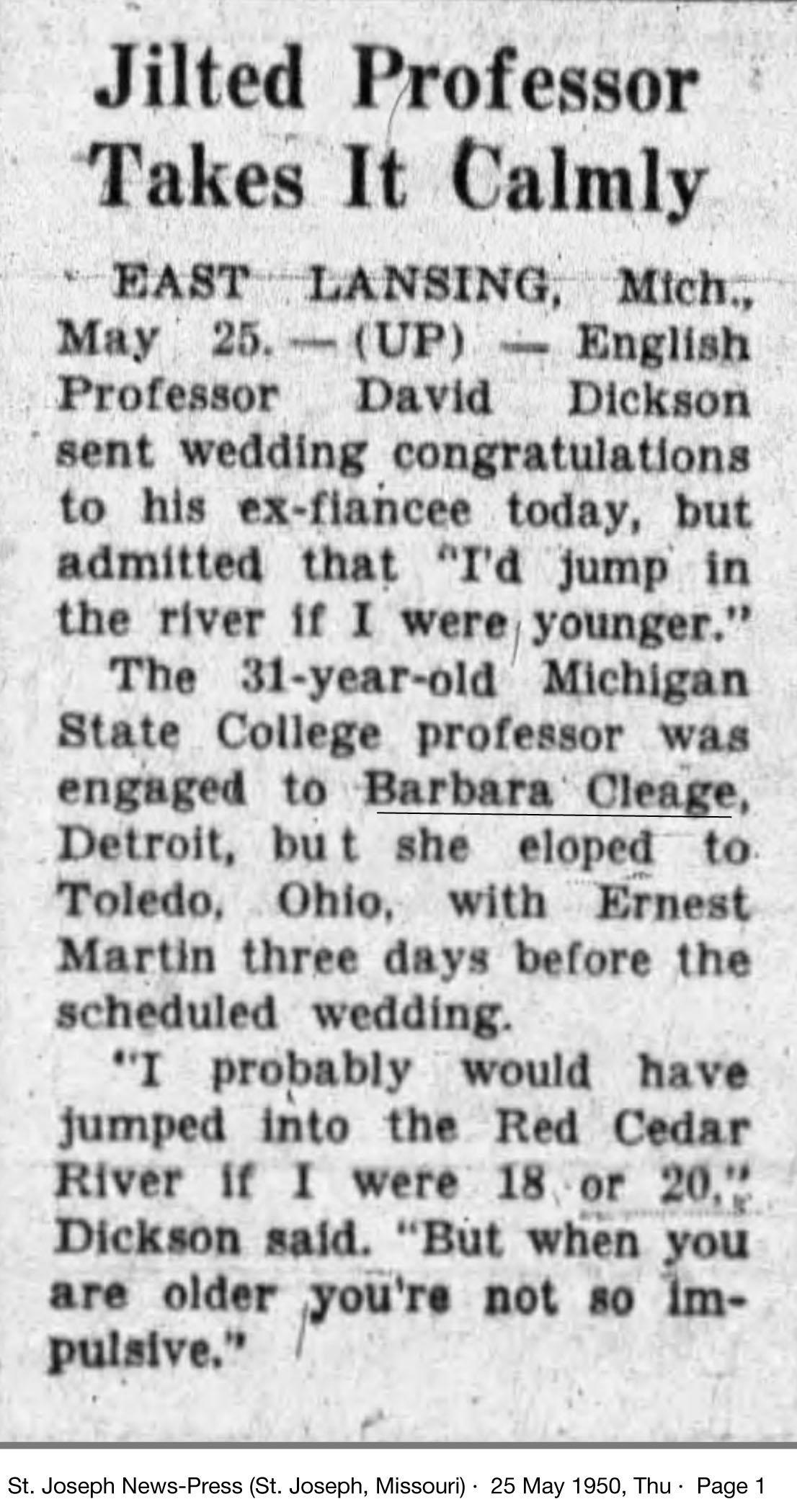

St. John’s and Dunbar Dispute is Settled

Out of Court Agreement Provides Church Pay League $11,000 for Two Properties

An out-of-court settlement of the long-standing property dispute between St. John’s Congregational Church and the Dunbar Community League, Inc., was announced jointly yesterday by counsel for the two groups, John T. Quirk, Jr., and Robert W. Bodfish for the church and Milton J. Donovan for the league. The settlement provided payment of $11,500 by the church to the league.

The terms will be incorporated in a consent decree terminating equity proceedings in Superior Court according to the attorneys. Their statement said, in part:

“St. John’s Church will pay to Dunbar Community League, Inc. $11,500. Dunbar will transfer to St. John’s the properties at 643 Union St. and 146-152 Quincy st., which are adjacent to the church property. The Dunbar organization will continue to occupy it’s present office location at 643 Union St., until Nov. 1, 1948.

“Suitable releases will be mutually exchanged to terminate all questions raised by the equity suit or outstanding between the parties.”

The proceedings against the league had aroused considerable controversy in Springfield’s Negro community, involving, as it did, one of the largest Negro congregations and an outstanding Negro social agency. It centered around title to several properties acquired by the church and St. John’s Institutional Activities, Inc., of which the Dunbar League is the successor.

Last spring, the church obtained a temporary injunction and restraining order against the league forbidding the league to dispose of the properties involved, and this was followed by issuance of an interlocutory decree, continuing the injunction and restraining order until final disposition, by Judge William C. Giles. The following parcels of real estate were listed in the case.

A house and lot at 49 Hancock St., two buildings and lots on Jennette Ave., interest in a house and lot at 59 Quincy St. and a house and lot at 610-612 Union St., all conveyed to St. John’s Church in 1915 under th will of Henrietta H. Coleman.

Property at 72 Marion, obtained by will, and in Pease St., owned by the church prior to Jan. 10, 1924, the date on which the Dunbar League’s predecessor acquired al the real estate by conveyance from the church.

The main point in the church’s bill against the Dunbar League was that the property originally was bequeathed for religious purposes and that the conveyances to the league’s predecessor were in violation of these purposes. The bill further said that the church was unable to enumerate other parcels of real estate and personal property of “great value” intended for and belonging to the church, because essential records were in the exclusive possession of the league.

It also set forth that the church believed the defendant was on the point of selling the real estate and averred that any transfer of the properties involved by the defendant would be illegal, and an unlawful diversion for purpose wholly foreign to the original purpose. Other properties later added in the equity bill were 81 Orleans St., 146 Quincy St., 150-152 Quincy St., 154-156 Quincy st., 43 Hancock St., and 616 Union St.

Court proceedings were begun several months before the recent death of Rev. W. N. DeBerry, pastor of St. John’s Church who, in later years, devoted his efforts largely to the Dunbar League.

St. John’s Congregational Church was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

Sources

St. John’s Congregational Church (Sanford Street Church, Free Church)

Springfield, MA – Our Plural History

Historic St. John’s Congregational Church to open New Worship Center

Rev. William N. DeBerry

Prophet of the Black Nation by Hiley H. Ward. ©1969 United Church Press

We never went to a parade but I remember looking out of our front door watching a religious procession going past our house. They carried large statues down the street.