After watching Episode 3 of Many Rivers to Cross in which the Civil War; black soldiers, contraband; freedom; 40 acres and a mule; suffrage and loss of it; the all black town of Mount Bayou, MS; lynching and finally Plessey vs. Ferguson were discussed, it took me a minute to come up with a tie in to my own family history to write about.

I began to think about my 2X Great Grandfather Joe Turner of Lowndes County, Alabama and how important land was to him and how it caused a riff between him and his son, my Great Grandfather Howard Turner. Something we always wondered about was how Joe Turner ended up with land at the end of the Civil War. Someone suggested it must have been Homestead Land. There is no indication that it was. I am going to write about Joe and Emma (Jones) Turner and their land.

As I started organizing materials, I looked to see if I could find any new information. In Mildred Brewer Russell’s book, “Lowndes Court House” on page 127 she says “Prominent Negro politicians during the carpetbag regime were Joe Turner, Oliver Marast, Jasper Cottrell, James Jackson, Tom Cook, Hamp Shuford, Frank Streety, Adam Lundy, Sam Robinson, Jule Cottress, Jerry Cook, Billy Spann, Cyrus Miles, Johnson Rambo, Robert McCord, Hope Harris, John W. Jones, and the three Carson brothers, Hugh, Will and Warren.” I wanted to find a record, another book, something that validates that the Joe Turner mentioned in the book, was my 2X Great Grandfather, Joe Turner.

I had no luck with the politics, aside from his name on a list of registered voters, but within 24 hours I found 2 new documents on Ancestry.com – the 1866 Colored Population Census and an Agricultural Census form for Joe Turner for 1880. Online I found a copy of a court case involving a land case between my 2X great grandfather and his son, my great grandfather.

__________________________

When shots were fired on Fort Sumter and the Civil War began in 1861, Joe and Emma (Jones) Turner were enslaved in Lowndes County, Alabama. I found Joe on the plantation of Wiley Turner but have so far been unable to find Emma and their children.

When the war ended and they were enumerated in the 1866 colored population census, they had 3 children under 10 – my great grandfather Howard who was three years old, his sisters, two year old Fannie and four year old Lydia. Joe and Emma were 25.

In 1870 they were farming. There were two more children, three year old Joe and 10 month old Anna. Neither of the adults could read or write. None of the children were old enough for school. Their personal estate was worth $300.

In the 1880 State Agricultural Census they farmed 76 acres, which they rented for cash. Farm implements and equipment were worth $100. Their livestock was worth $460 and included 2 milch cows; 12 other cattle (seven purchased in 1879 and one that died.); 20 swine; 36 barnyard fowl, who produced 100 eggs in 1879; one horse and four mules. They grew 25 acres of Indian corn, yielding 300 bushels; 50 acres of cotton yielding 12 bales and one acre of sugar cane yielding 48 gallons.

In 1880 US Census 16 year old Howard was clerking in a store. Joe Jr. was 13 and in school. Their sister Fannie no longer appears in the census and perhaps she was married or she may have died. I haven’t found a death record for her, I know that she died young. Several of her brothers named their daughters for her. My grandmother Fannie Mae Turner, was named for her Aunt Fannie. But that is getting ahead of myself. Another son, seven year old Alonza Turner, had joined the family since 1870.

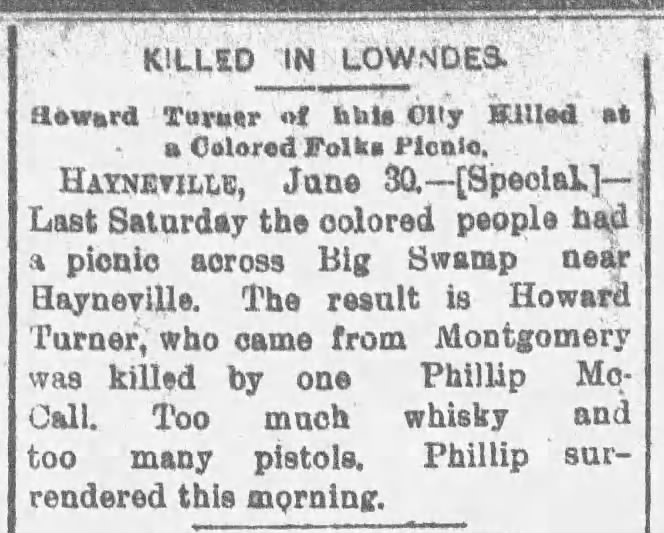

Howard Turner and Jennie Virginia Allen were married in June of 1887. My mother told me this story: Howard’s father, Joe Turner, gave them land to farm in Lowndes County, Alabama. Joe wanted the land to stay in the family forever. By 1890 Joe and Howard were arguing constantly about Howard and Jennie’s desire to sell the land and move to Montgomery. The day of the fateful barbecue, the arguments had been particularly violent. Jennie was in Montgomery visiting her parents with their two young daughters when word came that Howard had been shot dead at the barbecue.

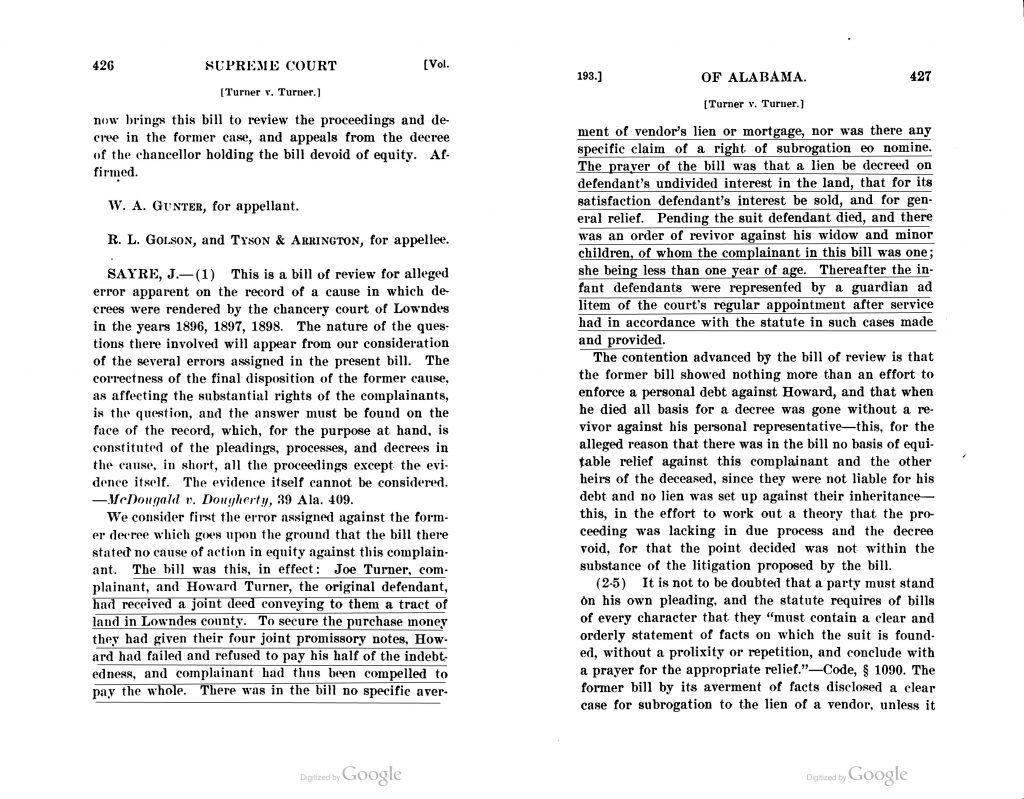

According to the court record, Joe and Howard had agreed to purchase some land together. They both promised to pay an equal share. When it came time to pay, Howard refused and Joe paid all of it. In 1890, my 2X great grandfather, Joe took Howard to court to recover his money. During the trial, Howard died. His youngest child, Daisy, was not yet one year old. The Court case against Howard was revived against his heirs and the Court ordered Howard’s interest in the land sold to pay the lien Joe had gotten in the Chancery decree in 1897.

In 1915 Daisy Turner brought a case before the Alabama Supreme Court to ask that she receive her inheritance from the sale of the land the original case concerned. By that time, 15 years had passed. Joe and Howard Turner were both dead. Joe’s second wife had moved to Montgomery with their children. Daisy lost her case. I think because her father hadn’t paid for his share of the land and so there was nothing to inherit. It seems that the land was sold after the first case. I will have to see if I can find the records of that case.

By 1900 Joe owned his own farm, although it was mortgaged. Emma could read and write, although Joe could not. She had given birth to 10 children. Only 3 were still living, Joe Jr., Alonzo and Lydia. Lydia’s two children, Anna Lisa and Joseph Davis, were enumerated with their grandparents.

Emma (Jones) Turner died around 1901. In 1902 Joe Turner, who was then 60 years old, married Luella Freeman who was 29 years old. He continued to farm and they had 9 children before he died at about age 80 in 1919. By 1930 Luella and most of her children were living in Montgomery. They ended up in Chicago, Illinois.I hope the land went to one of the older boys but I don’t think so.

Other posts I’ve written about this series:

Stolen from Africa

Escape – Dock Allen

Joe Turner – Land, Mules and Courts.

Hastings Street, Detroit 1941.

Love the story! Those Agricultural census sure tells a lot don’t they? Land loss was so prevelant in those days. I hope it stayed in the family.

I do to, but just watching them leave the land and head for Birmingham and Montgomery, I fear not. My husband worked for the Emergency Land Fund in the 1970s to try and stop land loss among black farmers. Didn’t work. So much land was lost.

Good post! Put together very well!

You should write that book, soon!

gem!

Why didn’t Joe purchased the land from Howard and allow Howard and his family to follow their dreams? Joe was probably disappointed that Howard didn’t want to share the dream he worked so hard to obtain and keep.

Or perhaps Howard agreed to buy the land in the first place because he knew it was his father’s dream. And they went forward with that deal but he realized that he couldn’t stay and farm. That it wasn’t his dream. Maybe my great grandmother hated the thought of living on the farm for the rest of her life. She grew up in Montgomery. So, Howard backed out, leaving Joe with a debt he couldn’t handle alone. So he took Howard to court to try and get him to pay his share.

It ended up that neither of them had that piece of land. It was sold following the first court case, it seems by court order. And my grandmother grew up half an orphan in her other grandfather’s house without knowing her father’s side of the family.

So, Joe was still in debt with the land when the separation occurred. Selling Howard’s portion would be the easy thing to do but selling would destroy Joe’s dream, which was destroyed and the relationship with his son. There were probably little hints before the purchase that this was not going to work.

I would think there had to be.

So sad that a father-son rift (father-son rifts are aways sad, though sadly common) mean that your grandmother did not grow up knowing her father’s side of the family. I like your generous interpretation of Howard’s motives. I don’t blame the son for not sharing the father’s dream. Holding on to land wouldn’t mean the same to him; getting off the farm would be his dream.

The theme of family fracturing seems to be a recurring theme in so many families; if we can tell these stories perhaps the cycle can be broken?

Loved reading this!

There have been other breaks in my family but none so complete as this one where the next generations never made a connection. I think that when people moved away from Lowndes County to Montgomery and Birmingham and then out of Alabama to Detroit and Chicago, it was hard to mend that connection that had been broken.

If only family members would remember that there is strength to be found in the connected family that is hard to replace. And if we could both accept differences and learn not to make it all about “us” and to speak up before you get in so deep you can’t get out without a break.

I’m glad you enjoyed reading it.

Kristen:

Have you thought of publishing all these beautiful pictures. I have been fascinated by your photo collection. I have learned to appreciate and hold on to those photos. I hope that you would give some thought to publishing. Take a look at http://www.snapfish.com

Shelley,

I am thinking about it. Thanks for the link.

Great story.

“Lowndes Court House” on page 127 she says “Prominent Negro politicians during the carpetbag regime were Turner, Marast, Cottrell, Jackson, Cook, Shuford, Sam Robinson, Cook, Miles, McCord, Harris, Jones.

I have found many of these surnames while doing research for my Lowndes County connections. I will need to find a copy of this book.

You may be able to get a copy here http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~allownde/research/gen_society.htm Good luck!

Thank you. This information may be helpful the next time I am in Lowndes County.