Slavery on the Cleage Plantations

This is a brief summary of Samuel, Alexander and David Cleage from 1810 to 1870 as the family went from enslaving no one, to collectively owning over 120 people. These are the plantations on which the people in this series lived during slavery.

Samuel Cleage

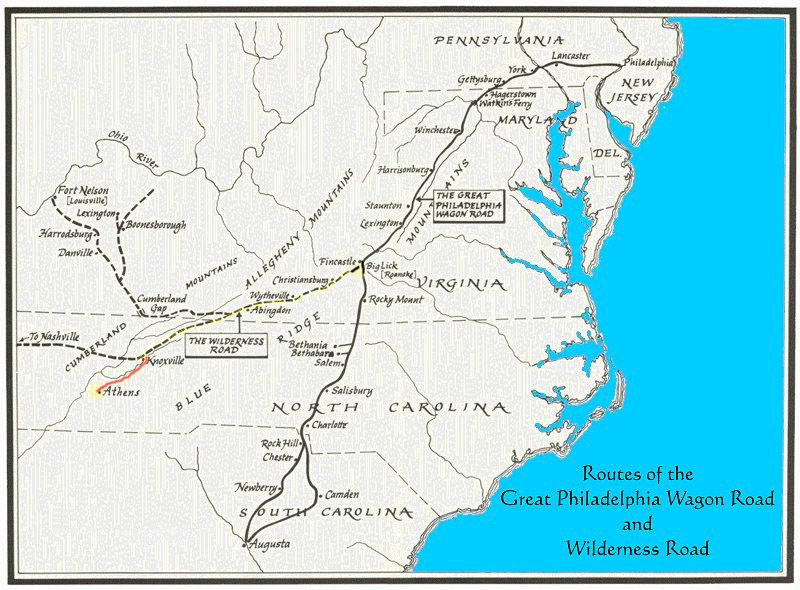

Samuel Cleage was born in 1781 in Pennsylvania. The family later moved to Botecourt, VA. His father, Alexander Cleage, had no enslaved persons according to the Federal Censuses he appeared in.

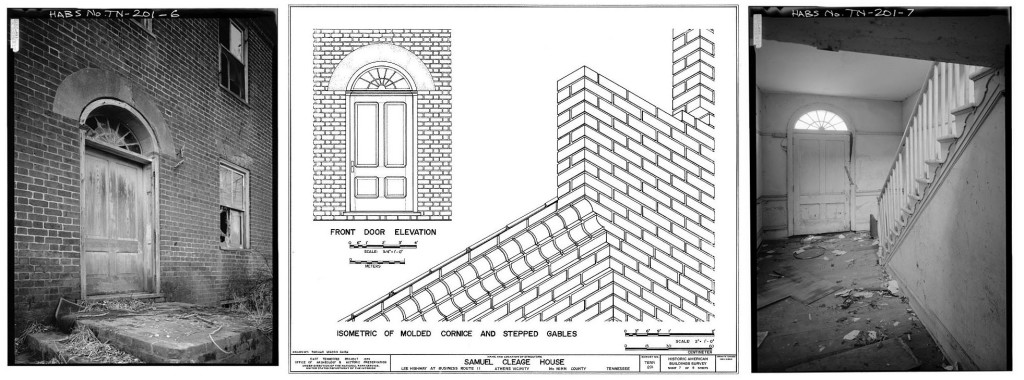

Samuel worked as a building contractor in Virginia. In 1810 he was 29, had a household consisting of 7 white people and 1 enslaved person. After his parents died in 1823 he moved his whole household to McMinn County, Tennessee. He was about 42 years old. Read about the move at C is for Cleage Bricks.

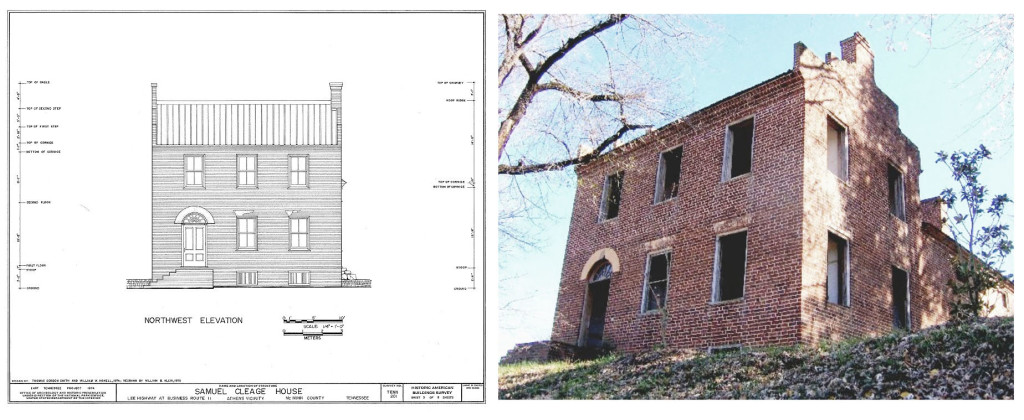

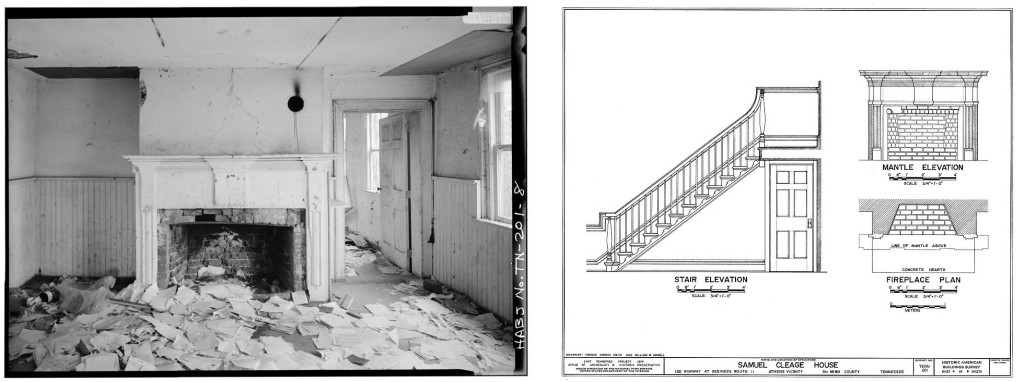

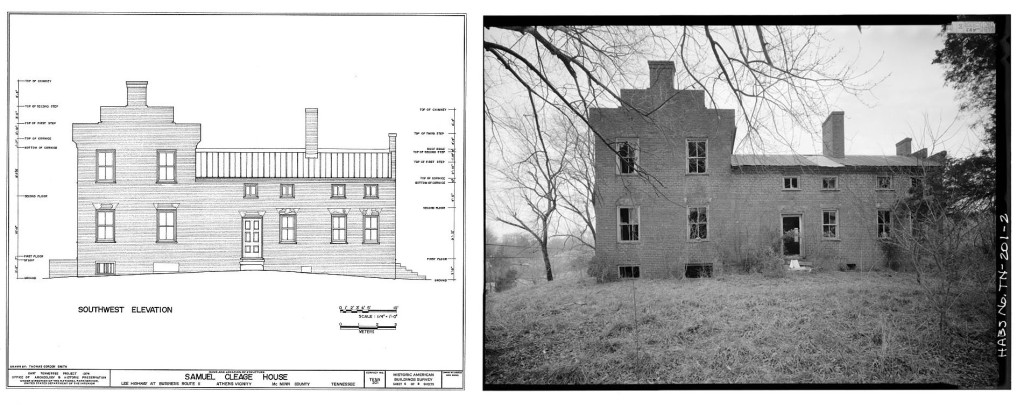

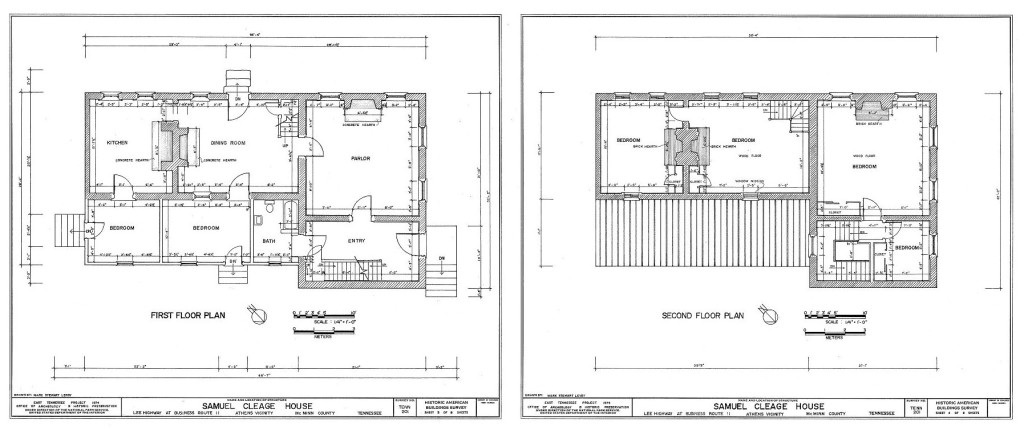

The trip took several years because he stopped to build brick houses at farms along the way, collecting pay in gold and enslaved people. Although some sources say that he arrived with hundreds of enslaved and barrels of gold, the 1830 Census lists a household of 4 free whites and 15 enslaved blacks. After arriving, Samuel picked out a parcel of about 1,125 acres and using enslaved labor, built a fine brick house. The land that Samuel Cleage bought was part of the land opened for white settlement when some Cherokee, hoping to profit from the already occurring influx of whites, signed the Calhoun Treaty. It was called the Hiwassiee Purchase.

In a 1834 agreement between Samuel Cleage and his overseer, 7 enslaved persons were named and 2 little boys were unnamed. Some of the tasks mentioned in the agreement are clearing land, distilling and planting. Article of Agreement Between Samuel Cleage and Overseer – 1834.

By 1840 the household consisted of himself and his wife and 23 enslaved people. Eleven are involved in agriculture. In the 1850 census Samuel and his wife shared their home with his son David, his wife and 2 small sons. They now owned 31 slaves, 1,200 improved acres and 20 unimproved with a value of $20,500. That translates to about $560.000 in today’s dollars. Samuel Cleage died in 1850 at age 69.

Alexander Cleage

Alexander Cleage, born in 1801, was the oldest son of Samuel and Mary Cleage. He married Jemima Hurst in 1832 when he was 31. She brought 4 enslaved women to the marriage. One was my 2X great grandmother. They were named in her father Elijah Hurst’s Will. The first census I found him was for 1840. There were 6 white family members and 4 slaves – 3 women and a boy. That is 1 less woman than the 4 that came to the marriage.

By 1850, Alexander was a bank officer. There were 9 white family members and 31 slaves, 24 women and 7 males. His real estate was worth $5,750. In 1852 there was some moving around of slaves from Samuel Cleage’s estate and Alexander came into possession of 12 named slaves. In 1857 there was a bill of sale for an unnamed slave.

In 1860, Alexander was a farmer with estate was worth $43,500 and a personal estate worth $55,000. There were 7 family members, 52 slaves and 8 slave dwellings. He wrote his Will that year and gave the names of the 12 slaves his wife received at her marriage and “their increase”, plus two men. I only recognize 2 of the names as being the same as those in Elijah Hurst’s Will.

In 1870, Alexander was a 69 year old farmer. He owned land worth $40,000 and his personal estate was worth $20,000. Two of his 2 children, a young man 23 and a girl 13, at home and both attended school during the past year. Everyone in the family was literate. There are no slaves in the household, but the 16 year old live in black servant is illiterate and she has not attended school during the past year.

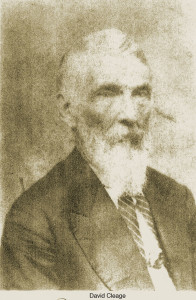

David Cleage

David Cleage was born in 1806 in Virginia. I have 2 bills of sale for 3 named slave boys, ages 10, 11 and 13 for 1841 and 1842. In 1846 David married Martha Bridgman. She brought at least 1 enslaved girl with her, Charlotte who was about 10.

In 1850, David Cleage was 44. He was a cashier at the bank in Athens, TN. His real estate is valued at $1,000. He and his family are sharing a home with his parents. He owns 32 slaves.

By 1860, the number has risen to 75 slaves living in 8 slave dwellings. He is still a cashier at the bank, real estate worth $2,000 and personal estate worth $90,000. The household includes 5 family members and an overseer.

In 1870 David was 64,a retired banker with real estate worth $18,700 and a personal estate worth $41,995. All 7 people in the household are literate. The children between ages 21 and 8 attended school within the last year.

Sources: I used documents founds on Ancestry.com and Familysearch.com, several bills of sale that I have copies of, “The Cleage Slaves and the Bricks of History” by Joe Guy and “Botetourt County, Virginia Heritage Book – 1770-2000”