As I was transcribing my grandmother Fannie Turner Graham’s records of her children’s births and deaths, I began to wonder about the lives of Dr. Ames and Dr. Turner (no relation) who attended these events. As I read about their lives in various online sources I also learned about Detroit race relations, some of which I knew but I had not put them together with the lives of my family and those they knew. I also realized some tie-ins with my paternal Cleage side of the family. They all get mixed up in this post.

On April 3, 1920 Mary V(irginia) Graham was born at home with Dr. Ames attending. My mother, Doris Graham Cleage did not remember him fondly. “It was a very difficult delivery, labor was several days long. The doctor, whose name was Ames, was a big time black society doctor, who poured too much ether on the gauze over Mother’s face when the time for delivery came. Mother’s face was so badly burned that everyone, including the doctor, thought she would be terribly scared over at least half of it. But she worked with it and prayed over it and all traces of it went away. Mary V’s foot was turned inward. I don’t know if this was the fault of the doctor or not, but she wore a brace for years.”

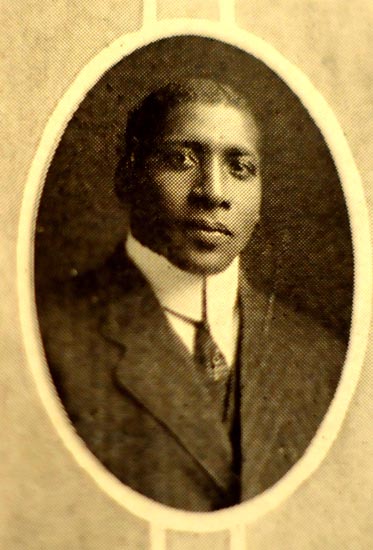

Dr. James Ames came to Detroit in 1894 after graduating from Straight University in New Orleans and Howard University Medical School in Washington D.C. He was elected to the Michigan State House of Representatives from Wayne County’s 1st district for a two year term, 1901-1902.

In 1900 the total population of Detroit was about 285,704. When my paternal grandparents, Albert B. and Pearl Cleage, moved their family to Detroit in 1915 the black population was about 7,000. By the time my maternal grandfather, Mershell C. Graham, arrived in 1917 the black population had soared to over 30,000.

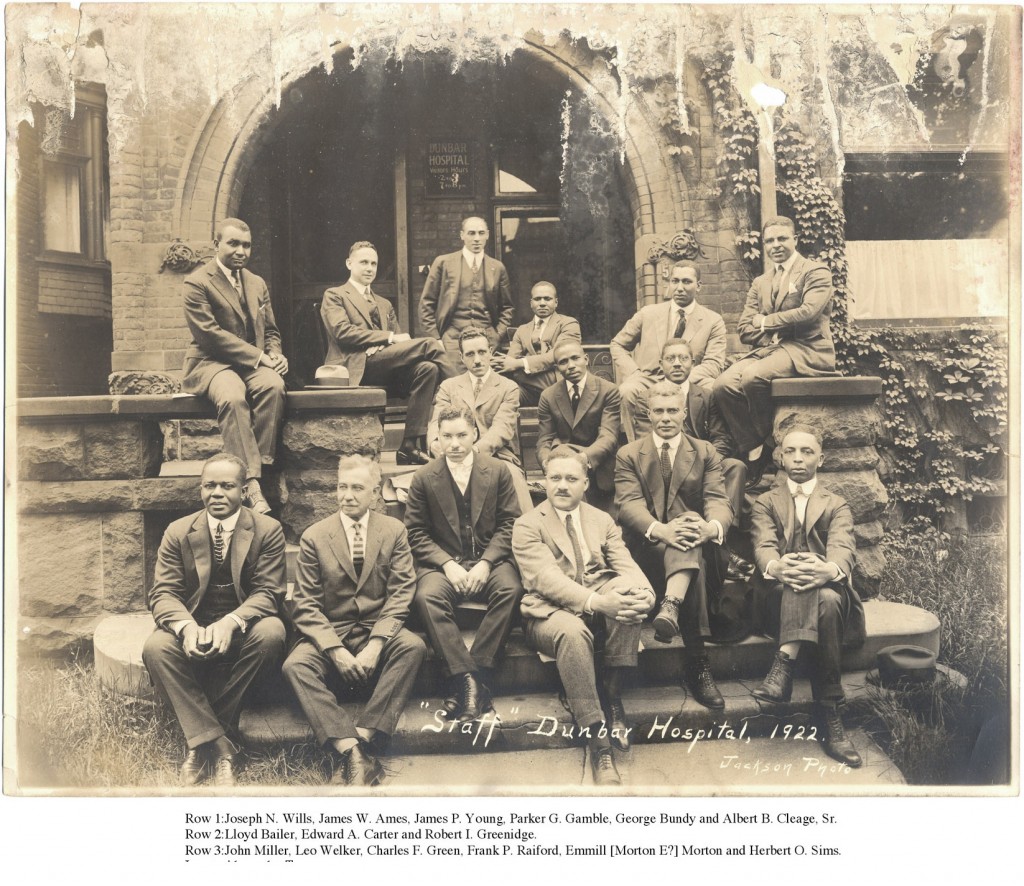

Black doctors were routinely denied admitting privileges at white hospitals. This meant their patients had to be admitted to the hospital by a white doctor. They were sometimes also denied the right to treat their patients once they were admitted. Often hospitals had segregated wards and once they were full, black patients had to find another hospital. In 1918, 30 black doctors came together and founded Dunbar Hospital. Dr. Ames was Medical Director and Dr. Alexander Turner was Chief of Surgery. My grandfather Dr. Albert B. Cleage was one of the doctors. Dr. Ames is first row second from left in the photo of the Dunbar staff above. My grandfather is first row, last one to the far right.

Fannie Graham’s second child, Mershell C. Graham Jr, was born June 10, 1921 at Dunbar Hospital with Dr. Turner in attendance. In that same year, membership in the Ku Klux Klan in Detroit totaled 3,000. The third child, my mother, Doris J. Graham, was born February 12, 1923 at Women’s Hospital with Dr. Turner attending. By that time membership in the KKK in Detroit was 22,000. In November of that year between 25,000 and 50,000 Klan members attended a rally in Dearborn township, which is contiguous with Detroit’s west side.

By 1925 Detroit’s total population was growing faster than any other Metropolitan area in the United States, the black population was over 82,000. Housing segregation was widespread, although there were neighborhoods such as the East Side neighborhood where the Grahams lived that black and white lived together without friction. Perhaps the area wasn’t posh enough to invite trouble. Maybe the large number of immigrants accounts for it. Unfortunately that was not the story citywide as people began to try and move out of the designated black areas into the other neighborhoods. Families moving into homes they had purchased were met by violent mobs that numbered from the hundreds into the thousands. This happened in 1925 during April, June, twice in July and in September.

RoNeisha Mullen and Dale Rich The Detroit News

While writing this I realized that in 1925, my father, Albert B. Cleage Junior, was 14 and attending Northwestern High school with the children of the families that forced Dr. Turner out of his home. The elementary schools for both communities fed into Northwestern High School, which my father and his siblings attended. No wonder my grandmother Pearl Cleage is famous for going up to the school and fighting segregated seating and other inequalities practiced at the time. Ironically, in the ’60s when my sister and I were living on Oregon Street, several blocks from where Dr. Turner tried to move in, and attending Northwestern High School, the community was 99 percent black.

On November 1, 1927 Mershell C. Graham Jr was killed when he was hit by a truck on the way back to school after lunch. He was taken to St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, a Catholic Hospital on Detroit’s East side. Dr. Turner was there with him when he died.

On September 9, 1928 Howard Alexander Graham was born at Woman’s Hospital with Dr. Alexander Turner attending. By 1930 Detroit’s population was 1,568,662. On March 4, 1932, Howard Graham died. I know that his first name was that of Fannie’s father. I wonder if his middle name, Alexander was for Dr. Alexander Turner.

Some links you might find interesting:

Part 1 – Births, Deaths, Doctors and Detroit – Grandmother Fannie’s Notes

The Sweet Trials: An Account

Click For other Sepia Saturday Posts

You have managed to bring history alive with this post. Those detailed stories are fascinating, and it’s great that you were able to place your own family in position whilst thse events were taking place.

Interesting history. I was surprised that Detroit's population changed so much in just a few years. I was also surprised that the KKK was so big there.

Fascinating story, as always.

I recently read about the saga of Dr. Ossian Sweet in Arc of Justice by Kevin Boyle. It's a frightening account, but also enlightening and inspirational.

Little Nell – Placing my family in events is what makes me interested in them.

Postcardy – The auto factories were taking off and people who needed jobs were coming to get them. Lots of people from the south came up, both black and white.

Christine, I read quite a bit on Ossian Sweet while looking for information and found that his 18 month old child and wife both died of TB in the years following. They never lived in the house. Sweet himself ended up committing suicide.

That's some story, and I appreciate your helping me, in a small way, to understanding something about Detroit and black history. This stuff I have only read about and seen in the movies, but of course it had many parallels in the country of my birth, Zimbabwe. Reading your accounts bring it home to me in a way that a movie can't.

A sense of place. You've nailed it, Kristin. It's not just the place (because as we know too well, places aren't permanent) but the time as well. You've made all the connections here.

Thank you for sharing so much personal history, fascinating read!

I get to visit the Detroit area every year but don't get into the city much. You have educated me about events that I would not have heard of otherwise.

I found this really engrossing reading, not least because my father was a Graham with a middle name of Turner. I'm fairly certain there is no link but it gave me a shiver all the same. 🙂

Such interesting history, such very hard times.

Wonderfully informative. And by now, I almost know your family and see myself as some kind of historical family friend. It is posts like this which make Sepia Saturday such a delight.

I wish you would compile your posts into a book. This needs to be on the shelves of Detroit libraries (and other places). I don't think people really understand how bad things were in the relatively recent past. The line that really got me was this one: At gunpoint, two men forced Turner to sign his deed over to them and, with the help of the police, had the Turner family escorted out of the house.

Knowing the police assisted makes the whole incident even worse.

Kathy, I do want to put them into a book. Just haven't gotten that far yet. After writing this I thought about my husband's family in St. Louis. They were firebombed when they moved into a white neighborhood when he was a baby in 1945 in St. Louis. They had must moved up from Arkansas. And I remember in the 1960s, when I was in high school, my family bought a weekend place outside of Detroit and came up the next weekend with extended family and friends. The man who sold it to us came over and said that we shouldn't bring black people up there and my uncle told him we were all black. At some point he threw the check into the car, because my uncle wouldn't take it back and said the sale was off. Who wants to live around people like that? We didn't and bought some place else.

Very enjoyable to read. Very alive with history.

Excellent post – both fascinating and sad. I am so glad that things are so much better now. Particularly among the up-and-coming generation who integrate without a thought and step up to discourage prejudice.

When you publish, I will gladly buy the book!

So much sorrowful history here which you have done an outstanding job presenting. Having her face burned of ether while in childbirth is just mind blowing, good grief! I am currently reading "American Experience" by David McCullough and learning about the practice of medicine back then, which was not at all civilized. Many of the wealthier medical students journeyed to Paris to study. One student observes how the French at the time, mid to late 1800's, were more hospitable to blacks than he had been accustomed to in the state's, which made him realize that was not right what was happening in the US. Yes indeed the north, industrialized or not had heavy racism.

while segregation may seem an idiotic idea, it did happen. must have been frightening back in the days with those KKK people. they tried to come to Canada, but it didn't work out too well for them here, except in the prairies, for a while… i've much enjoyed this other chapter in your history. keep'em coming, m'ame!!

:)~

HUGZ

Richard Wright wrote about (paraphrasing from memory) "the fury in every black man's soul," having to be humiliated and threatened — no matter how educated and erudite. I agree with Kathy that this family history information should be in an archive in Detroit or (elsewhere where African American history is stored) for future researchers.