Today I received the following article from my friend historian Paul Lee via email. I will let him introduce the article.

“Alice Dunbar-Nelson was the first wife of famed poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Sadly, until recently, Dubar-Nelson’s own considerable gifts as a poets, as well as her journalism and political activism, were overshadowed by her illustrious first husband’s (overblown) legend.

The Black Dispatch was one of the most respected “black” newspapers of its time. It was published by the estimable Roscoe Dunjee, who was independent-minded enough to be a card-carrying member of the NAACP, but also remain an open (if occasionally gently critical) admirer of Marcus Garvey and a strong supporter of Mr. Garvey’s program of ‘African Redemption.’

Mr. Dunjee, who was proud to be one of Oklahoma’s ‘black’ pioneers, opened the pages of his paper to regular reports from the branches, chapters and divisions of Mr. Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), which had a vital presence throughout the Sooner State.

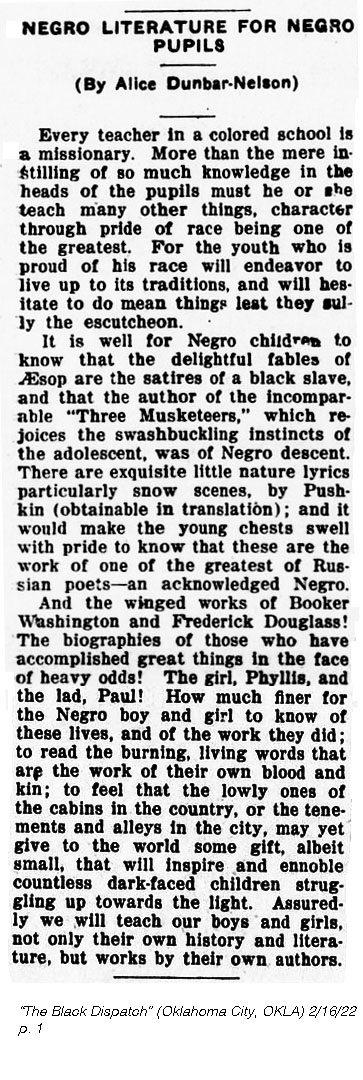

‘Negro Literature for Negro Pupils’, The Black Dispatch (Oklahoma City, Okla.), Feb. 16, 1922, p. 1.”

Great stuff! Thanks Paul!

You are so right, Alice was overshadowed by Paul. I never, before this time heard of her. Lovely article.

Here are a few links to her poetry – http://allpoetry.com/Alice_Dunbar-Nelson

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/237230

It is interesting to read the literature suggestions. My sense is that so many important teaching materials that were used in Black schools–as well as many of the records of these schools–have been lost over the years.

Those books are all still around, although some now seem old fashioned. Although records have been lost, there seem to be quite a few records still available in different states, although I have yet to try and find any for my family.

Always a woman in the background

I grew up reading the literature that she mentions and her husband poetry. My mom would read His poetry to us as chilren my favorites were those in dialect. Curious as to why Paul in his introduction refers to P L Dunbar as “overblown legend”

Here is Paul Lee’s reply to the question.

Dear Kris,

I described Paul Laurence Dunbar’s legend as “overblown” because I’m a child of the 1960s, which is when my critical lens was developed. That is, I was shaped by the aesthetic of the cultural wing of the Black Power upsurge, known as the Black Arts Movement, which was popularized by Amiri Baraka, formerly LeRoi Jones, who made his transition a few days ago.

That is, I’m a black nationalist and, because of your beloved father, a Black Christian Nationalist.

Also, I studied “black” history at the culturally reactionary Howard University — fortunately for me, during the dawn of poet Sterling A. Brown’s long, rich life.

There I learned that Dunbar’s poetry, while celebrated and even treasured by many “black” people during his lifetime and in the first two decades after his 1906 death because he was a pioneer and a respected “black” literary figure (which is why so many segregated or separate “black” schools were named in his honor), his dialect poetry usually reenforced the racist stereotypes of happy plantation “darkies,” which was both embraced and mimicked by bigoted “white” poets, including such scum as Joel Chandler Harris and Thomas Nelson Page, both famous apologists for the enslavement of our ancestors.

Thus, I agree with Baraka’s observation about how Dunbar, who functioned within the limited “space” afforded “black” creative artists of his time, was used by the enemies of “black” people to their disadvantage:

“…Paul Laurence Dunbar and James Weldon Johnson are raised to the top rank [in ‘black’ literature courses], but an analysis of the content of these men’s works is made vague or one-sided. We are not aware perhaps that for all the positive elements of Dunbar’s work, his use of dialect, which is positive insofar as it is the language of the black masses, is negative in the way that Dunbar frequently uses it only in the context of parties, eating, and other ‘coonery.’ Most of Dunbar’s ‘serious’ poetry is not in dialect.

“Dunbar was deeply conservative, and his short story ‘The Patience of Gideon’ shows a young slave, Gideon, who is put in charge of the plantation as the massa goes off to fight the Civil War. Gideon stays despite the masses of slaves running away as soon as massa leaves. Even Gideon’s wife-to-be pleads with him to leave, but he will not. He has made a promise to massa, and so even his woman leaves him, alone with his promise to the slavemaster” (Amiri Baraka, “The Revolutionary Tradition in Afro-American Literature,” in William J. Harris, ed., The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader [New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 1991], p. 316).

However, in the wake of World War I, and particularly after the infamous “Red Summer” of 1919, when racist “white” mobs attacked mostly-“black” communities thruout the country, the greater cultural “space” allowed artists like Claude McKay to write his revolutionary poem “If We Must Die” (about this “racial” holocaust), which viscerally challenged and overturned “white” people’s comforting stereotypes, which had previously defined “black” people.

This is poetry that I, as a child of the sixties, could identify with — because it represented a free spirit, not one, like Dunbar’s, hobbled and dwarfed by the psychic, emotional and cultural tyranny of “white” supremacist ideology and its practical expression, the Jim Crow regime.

Ironically, Dunbar’s mostly-forgotten wife, Alice, evinced little, if any, of Dunbar’s limitations. Her poetry and journalism were often bold and assertive, which is why I was glad to spotlight her.

I have the honor to remain

Your Li’l Bro’,

Paul

Knowledge is power. Much respect

Shelley,

I’m so glad you came back and read Paul’s response.