Earlier I posted some newspaper notices seeking lost family members after the Civil War. My historian friend, Paul Lee, left a wonderful comment taken from two articles he wrote for “The Michigan Citizen”. It is reprinted here, with permission. You can read the previous post at “I have not seen him since the war“.

[Introduction to an article that was published, in slightly different form, in “The Michigan Citizen” (Highland Park), Feb. 13th-19th, 2000]

Compiled and edited by Paul Lee

Special to The Michigan Citizen

“My mother…was born in Virginia and was one of ten children. She and two sisters were sold to slave traders when young, and were taken to Mississippi and sold again…. She often wrote back to somewhere in Virginia trying to get track of her people, but she was never successful. We were too young to realize the importance of her efforts, and I have never remembered the name of the county or people to whom they ‘belonged.’”

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the uncompromising newspaper editor, anti-lynching campaigner, and feminist wrote this moving passage about the enslavement and forced separation of her mother and aunts some 60 years after Emancipation ended the formal bondage of black people in the now re-United States.

Though written for her autobiography, published after her death as “Crusade for Justice,” its details and tone closely resembled the spare, often poignant search notices placed in black newspapers throughout the nation for at least four decades after the end of the Civil War.

Though Wells-Barnett did not indicate it, her mother might have placed such a notice as part of her “efforts” to find her lost siblings.

We have compiled and edited 41 search and reward notices from six black papers representing four states and one territory (Tennessee, South Carolina, Texas, Kansas, and the Oklahoma Territory, respectively) and four regions (the Border-South, South, Gulf States, and Southwest).

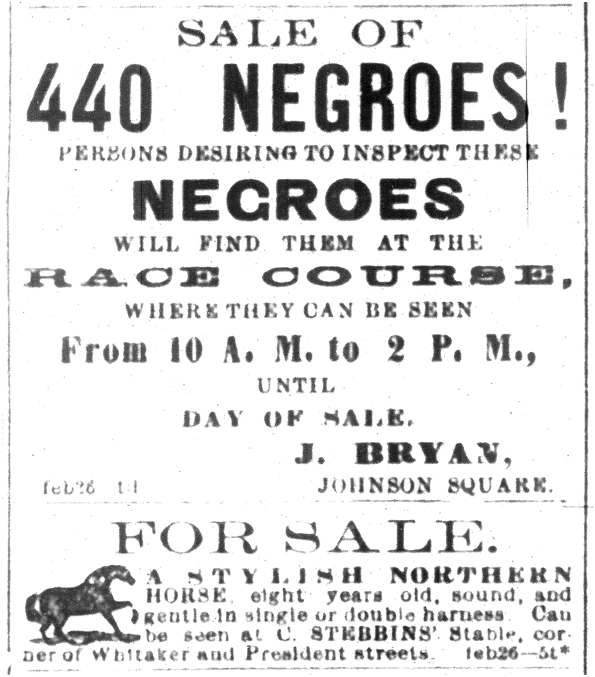

Outside of legal notices, black people usually appeared in at least two other ways in the classified pages of 19th-century papers. Firstly, as, most often, nameless property in for-sale ads, such as one that advertised “ONE Likely Negro Girl, in her 15th year — a first rate house servant, Also — one new first class top Buggy, and Harness complete. Enquire immediately of John P. Hubbell” — the latter reference underscoring her condition as only one of several commodities being offered.

Firstly, as, most often, nameless property in for-sale ads, such as one that advertised “ONE Likely Negro Girl, in her 15th year — a first rate house servant, Also — one new first class top Buggy, and Harness complete. Enquire immediately of John P. Hubbell” — the latter reference underscoring her condition as only one of several commodities being offered.

This notice appeared in “The Weekly Tribune” of March 26, 1852, which, ironically, was published in a small Missouri town named Liberty.

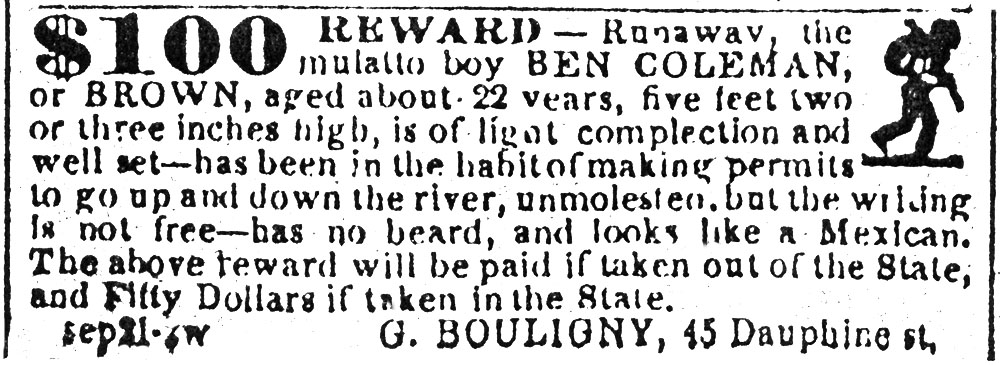

Secondly, in fugitive slave notices, often illustrated with the familiar “running man,” which did, however, include one notable detail lacking from most for-sale ads — the name of the now “lost” property.

Secondly, in fugitive slave notices, often illustrated with the familiar “running man,” which did, however, include one notable detail lacking from most for-sale ads — the name of the now “lost” property.

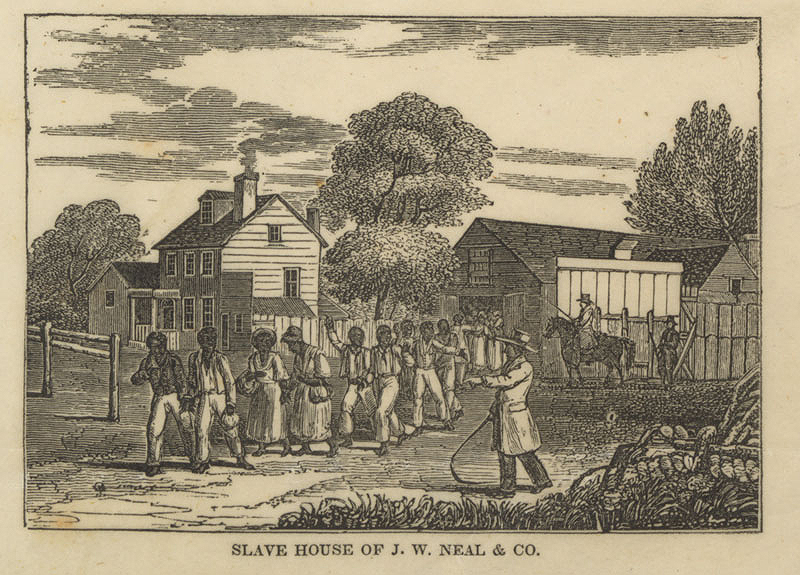

Because of the nature of enslavement, which saw and treated black people as property to be bought, sold, used, and disposed of, and the massive social displacements during and after the Civil War, few black families were left intact by war’s end.

Search notices offer compelling testimony of the strength of black family bonds. Ironically, these valuable sources of information are rarely used by historians and genealogists.

. …

[Introduction to an article that was published, in abridged form, in “The Michigan Citizen,” May 13-19, 2001]

INFORMATION WANTED!

More African American Search Notices After Slavery, 1892, 1895

Compiled and Edited by Paul Lee

Special to the Michigan Citizen

“INFORMATION WANTED OF my husband and son. We were parted at Richmond, Va., in 1860. My son’s name was Jas. Monroe Holmes; my husband’s name was Frank Holmes. My son was sold in Richmond, Va. I don’t know where they carried him to.

“…I and five children…were sold to a [slave] trader who lived in Texas. I am now old, and don’t think I shall be here long and would like to see them before I die. Any information concerning them will be thankfully received by Eliza Holmes, Flatonia, Fayette Co., Tex.”

This moving plea for information, published in September 1895, is but one example of the poignant appeals that appeared in black newspapers from the Civil War to the first years of the 20th century.

Placed by black people in search of relatives and friends that were separated from them — often by force — during the dark period of enslavement, these notices usually bore the headings “LOST!” or “INFORMATION WANTED.”

Last year, we were proud to reprint a compilation of 41 of these notices, published in four states and one territory (“LOST! African American Search Notices After Slavery, 1865-92,” Feb. 13-19, 2000).

More Notices

The response of our readers to these notices was immediate and emotional. Many of the calls, letters, and comments that we received were nearly as poignant as the notices themselves.

We are, therefore, honored to publish 28 additional notices, compiled and edited from two 19th-century black newspapers — one from “The Langston City Herald,” Jan. 28, 1892, and 27 from “The Christian Recorder,” Sept. 12, 1895.

“The Langston City Herald,” published in the old Oklahoma Territory, was the “booster” organ for Langston City, one of the first, and the most famous, of the black-governed towns in what is now western Oklahoma.

It is also believed to be that territory’s first black paper.

“The Christian Recorder,” then published at Philadelphia, Penn., is the organ of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church. It is one of the oldest black papers in the world.

The “Recorder,” now published at Nashville, Tenn., was an important medium for news and opinion about black people, not only in the U. S., but also thruout the world.

The notices demonstrate that, though slavery inflicted lasting damage on black families by ruthlessly dividing them, it could not erase the love and loyalty that family members felt for one another — even after decades of separation.

The notices make clear that, through all of slavery’s horrors, many bondsmen and -women found reasons and ways to maintain their sense of familyhood, and acted upon it when freedom finally arrived.

Freedom Trails

Some separations were voluntary — though no less painful. Tens of thousands of bondspersons managed to escape from enslavement every year, but only a fraction were able to remain free and begin new lives elsewhere.

Most were recaptured and returned to their owners. Those considered “runners” were usually sold or traded.

In their groundbreaking 1999 study “Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation,” John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger assert that, contrary to popular belief, the destination of many “runaways” was neither the northern United States nor Canada.

Instead, most fled to nearby plantations, cities, or other parts of the South.

Even less well known is the fact that some joined “maroon” colonies of fugitive and free blacks that were concealed in woods, swamps, and backcountry.

During the Civil War, the Union Army’s relentless march to smash the Confederacy created new openings. While most of the newly freed persons remained bound to the land, some followed after and assisted their liberators.

Others left in search of relatives, or tested their new freedom by doing what had previously been illegal — going wherever they wished to.

Some, evidently traumatized by slavery and war, simply wandered off, never to be heard from again.

This is heartbreaking.

It is truly heartbreaking. Do you know if any of these notices were successful in reuniting families?

Thanx, Carolyn. I don’t know if anyone found family members or friends thru the search and reward notices. If they did, I didn’t run across any published statements to this effect, although I pray that some were successful. However, as Kris has stated, these notices can help genealogists and family history scholars to reconnect family members across the generations.

man’s inhumanity!

i feel their parts and then i wonder why?

good article.

Very good read! I am amazed at some of the things that are popping up when I google about an African American church that I am attempting to purchase. One map I found, from the later half of the 19th told me that it was and labeled “negro” I think I my jaw hit the floor! I didn’t think this run down foreclosed property in a mainly white community would possible have a history like this. I personal hope that I can get to this place before the wrecking ball, but as money talks it is a struggle for me. I hope with the purchase and restoration that I can find and save things like this for future generation. I person hope that I do find slavery information, that would contain life stories, photos and names. I person plan to do everything in my power to record everything online and on hard copies. I was already considering fireproof record storage to keep the history the newer church may have on file in. I have great plans to make the property something amazing, positive and focusing on preserving the lost history of that area. It personal may be hard quest but I cherish history as a thing that our younger generation needs to learn to prevent future mistakes. It is great to read this, and as heart breaking as this is. It is something that we must not forget and we need to take it to heart to even help some of these lost souls still searching for loved ones.