Today, a guest post from my sister, Pearl Cleage, written about our mother. Doris Graham Cleage.

Doris Cleage 1923 – 1982

Doris Cleage 1923 – 1982

My favorite memory of my mother takes place in one of my least favorite environments: the airport. The Detroit airport at that. I had just flown in from D.C. and the plane was rolling slowly toward the gate, giving me ample time to worry about the next three days.

In the best of times, arrival and departure gates are not great places to play out complex emotional moments. The lighting is terrible and you’re surrounded by strangers. If you’re leaving, it’s too late to start any significant conversation, but not yet time to kiss and say good-by. If you’re arriving, first there is the interminable wait to actually deplane, the impatient jostling of people in the jet way, anxious to get to the concourse so they can jostle their way down to baggage claim, if they were foolish enough to check one.

Once there, those like me being met by friends, lovers or family members try to accomplish the almost impossible task of hugging hello without bumping noses while juggling belongings and trying not to get trampled by the jostlers who are now breathing down your neck as the bags begin to tumble to the carousel and for the merest fraction of a second, you wonder if the trip was even worth it.

And then I saw my mother. She was standing at the agreed upon meeting place, surrounded by a crowd of people, all anxiously scanning the new arrivals just like she was and my first thought was: When did she get so tiny? At just under five foot two, she was dwarfed by the people on either side, even standing between them on tiptoe, searching the sea of strangers for her baby’s face. She looked worried and frazzled and, in the weird way that happens with post-middle aged parents who are seldom seen, suddenly older; more fragile; more vulnerable.

The fragility is what startled me. When had this change occurred? How long had it been since I had actually laid eyes on her? Too long, I knew, but the distance was necessary to insure my emotional survival. I loved my mother, but like most of the women on both sides of the family, including me, she had a mean streak that could manifest itself in harsh judgments about any and everything. That made moments like the one we were now approaching even more fraught with emotional peril since the last thing I needed was a critique of my behavior. I was just emerging from a series of ill-conceived moves both professional and romantic that resulted in a tearful phone conversation during which my mother asked me the worst question in the world: What were you thinking? The next three days were supposed to give me an opportunity to respond.

Please, God, I thought, let this be a good visit. By that I meant one with a relative lack of family drama (possible, but if past is truly prologue, not likely), and maybe, if I was very patient and very lucky, a moment or two where my mother and I could sit together and talk calmly like two grown women about where we were in our lives.

Even as the thought of such a conversation popped into my head fully formed, I knew it wasn’t going to happen. My mother was not a share your deepest secrets kind of woman. She didn’t solicit your opinion because she truly didn’t care what you thought, a trait I admired even while it terrified me. She married brothers, but was so unconcerned about the resulting gossip that I never even knew her behavior was perceived as scandalous until I heard two women discussing it in the seat behind me on the bus all the way home from ballet class at Toni’s School of Dance Arts.

Like the song says, she had paid the cost to be the boss, and while there was in my mother a deep disappointment at some of the ways her life had turned out, she was prepared to live with the consequences of her decisions without complaint. Heart to heart discussions of what she might have done or said differently held no interest. On the contrary, such unsolicited opinions were certain to evoke a look of such amazed indignation and displeasure that all you wanted to do was take back your feeble offering and beg her humble pardon for having had the temerity to make a suggestion about how she lived her life.

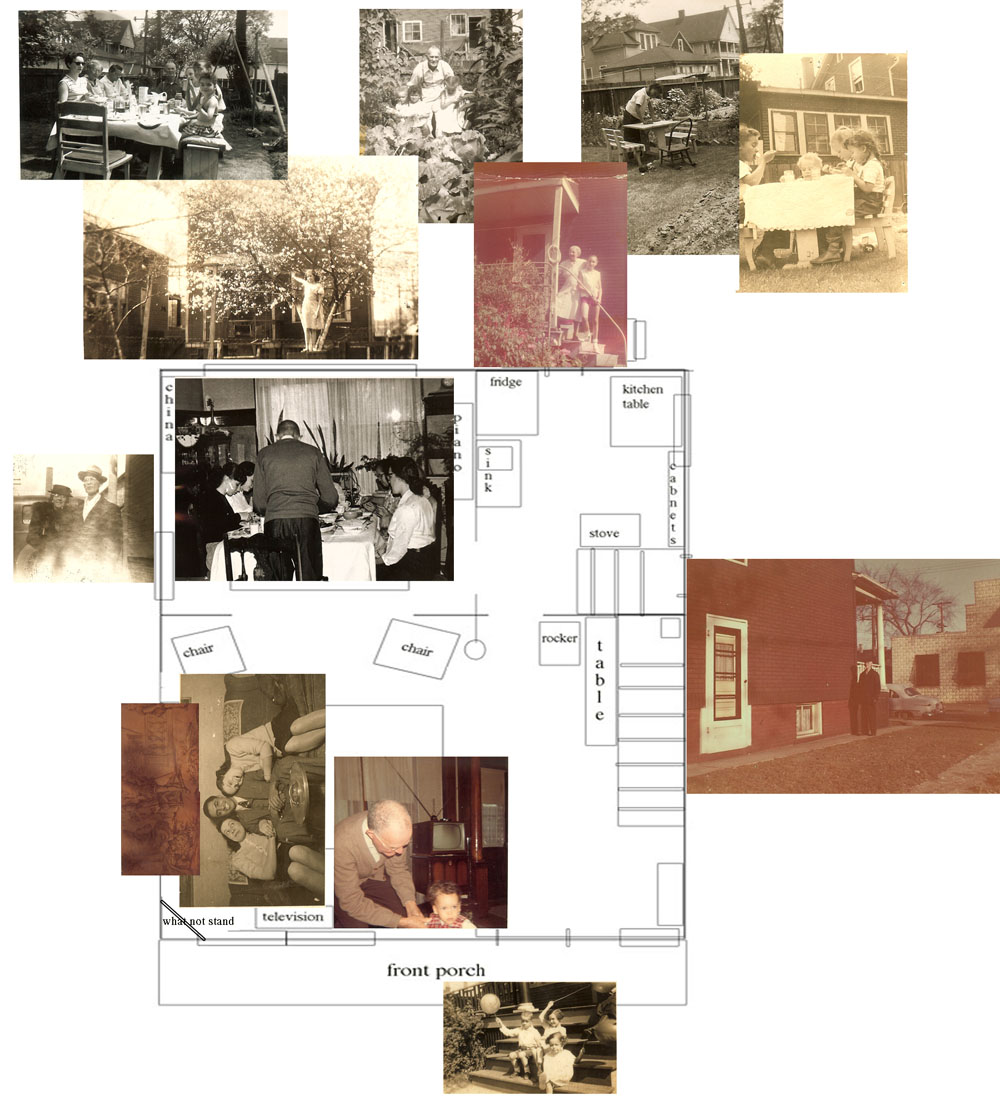

But I had a plan. I would ambush my mother with a fresh pot of peppermint tea in a sunny corner of her kitchen. I would put on a record of Leontyne Price singing Puccini, confess my sins and gently begin to pick her brain. I wanted that conversation. No, I needed it. My life was undeniably a mess and I had exhausted my ideas about how to make it better. The moment, I decided, had arrived for my mother to tell me the womanly secrets and ancient female coping mechanisms she’d been withholding until I was ready.

Well, I was ready now. There were so many questions I needed to ask; about her, about me, about whether or not work was worth the risk and love was worth the pain. You know, those questions. The problem was, where to begin? With her journey or mine? My mother was an archeologist trapped in the body of a first grade teacher. She longed to ride camels and see the pyramids of Egypt, but had to settle for the west side of Detroit and a few weeks in Idlewild at the end of the summer, having cocktails lakeside with well manicured doctors wives, all the time dreaming of the shifting white sands of the Sahara.

Could I ask her how it felt to see so much less than you could imagine? Could I ask her why she did it? Could I ask her how she had survived the loss of all those adventures and the stifling of all those dreams? Could I ask her if she thought I could survive it, too? And last but not least, could I ask her if she still loved me even in the midst of all my flopping and floundering and foolishness?

So there it was at last. I had buried the lead, but then my mother spotted me and however long it had taken to stumble upon the real question, her face at that moment was the real answer. There was so much absolute, unconditional, unequivocal, pure, joyous love shining in her eyes as she threw up her hand and hurried toward me that the force of it made me stumble and I almost dropped my bag.

Now I am not a mystical person, but I felt my heart crack and open that day to welcome the gift she was giving me and I understood that there is only one answer to all the questions that were driving me crazy: love/love/love/love/love.

Suddenly the fantasy conversation I’d been hoping for was just that – someone else’s fantasy. My mother and I didn’t need a cozy sunlit corner and a steaming pot of peppermint tea. We had each other. Then we bumped noses and she hugged me so hard she didn’t seem fragile at all anymore, which is, of course, tangible proof that the power of love can strike anywhere, anytime. Even when the lighting is absolutely terrible.

____________________________

Another post about my mother you may find interesting- GrowingUp – In Her Own Words,

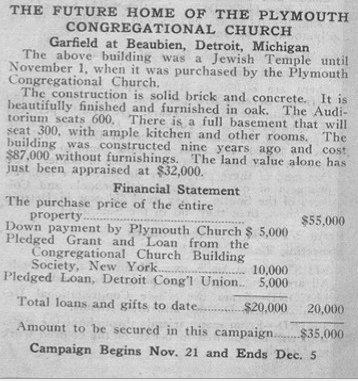

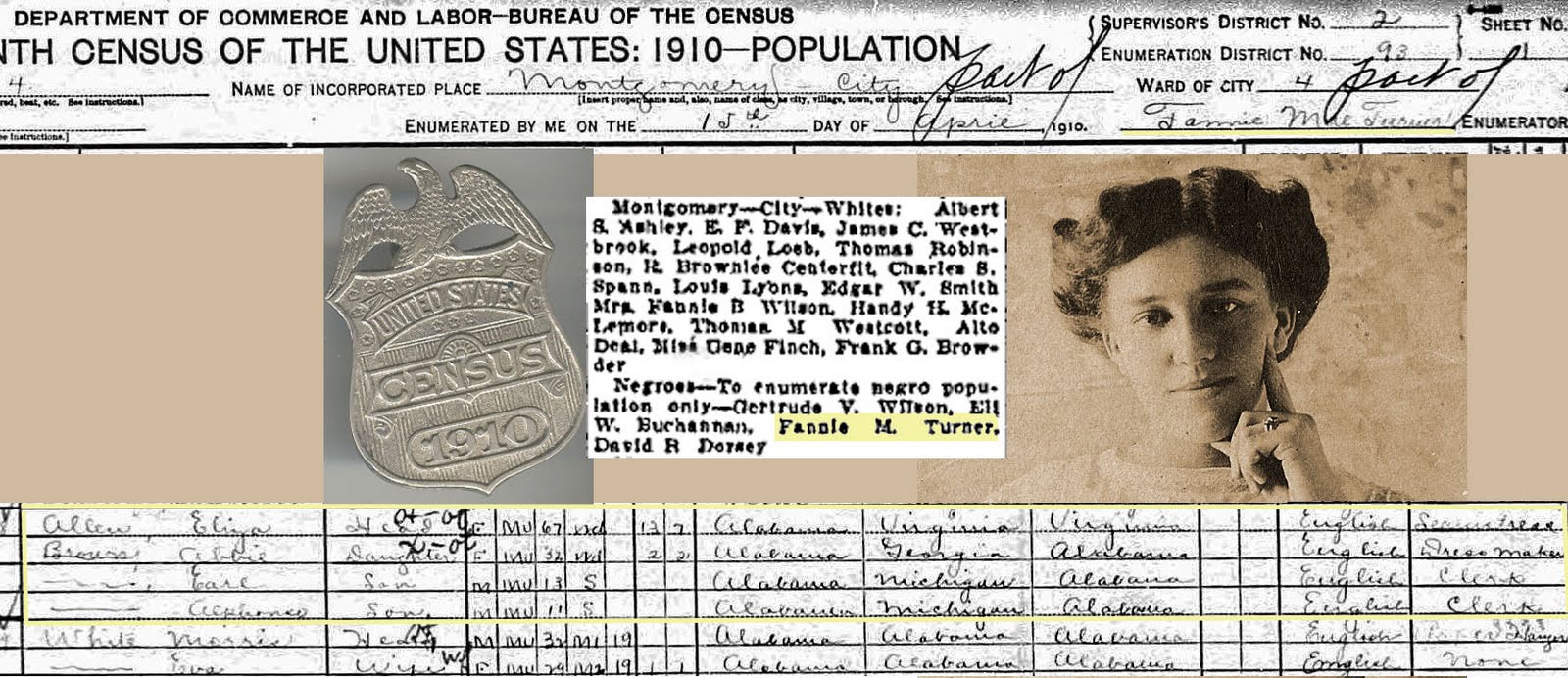

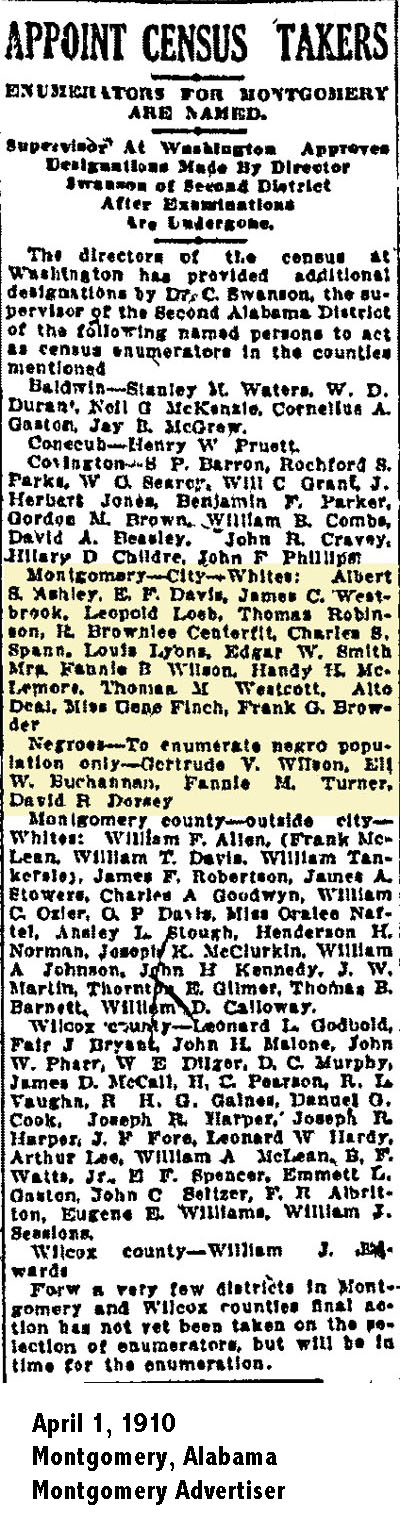

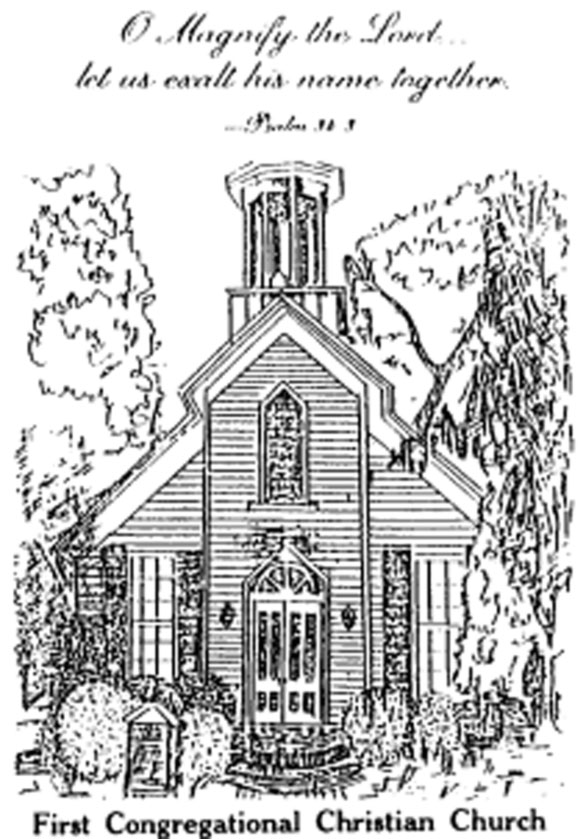

Northern Congregationalists came south to Montgomery, Alabama after the Civil War. First Congregational Christian Church was founded in 1872. They also supported a school nearby. My grandmother, Fannie, attended both the school and the church. She met her husband, Mershell, in the church.

Northern Congregationalists came south to Montgomery, Alabama after the Civil War. First Congregational Christian Church was founded in 1872. They also supported a school nearby. My grandmother, Fannie, attended both the school and the church. She met her husband, Mershell, in the church.